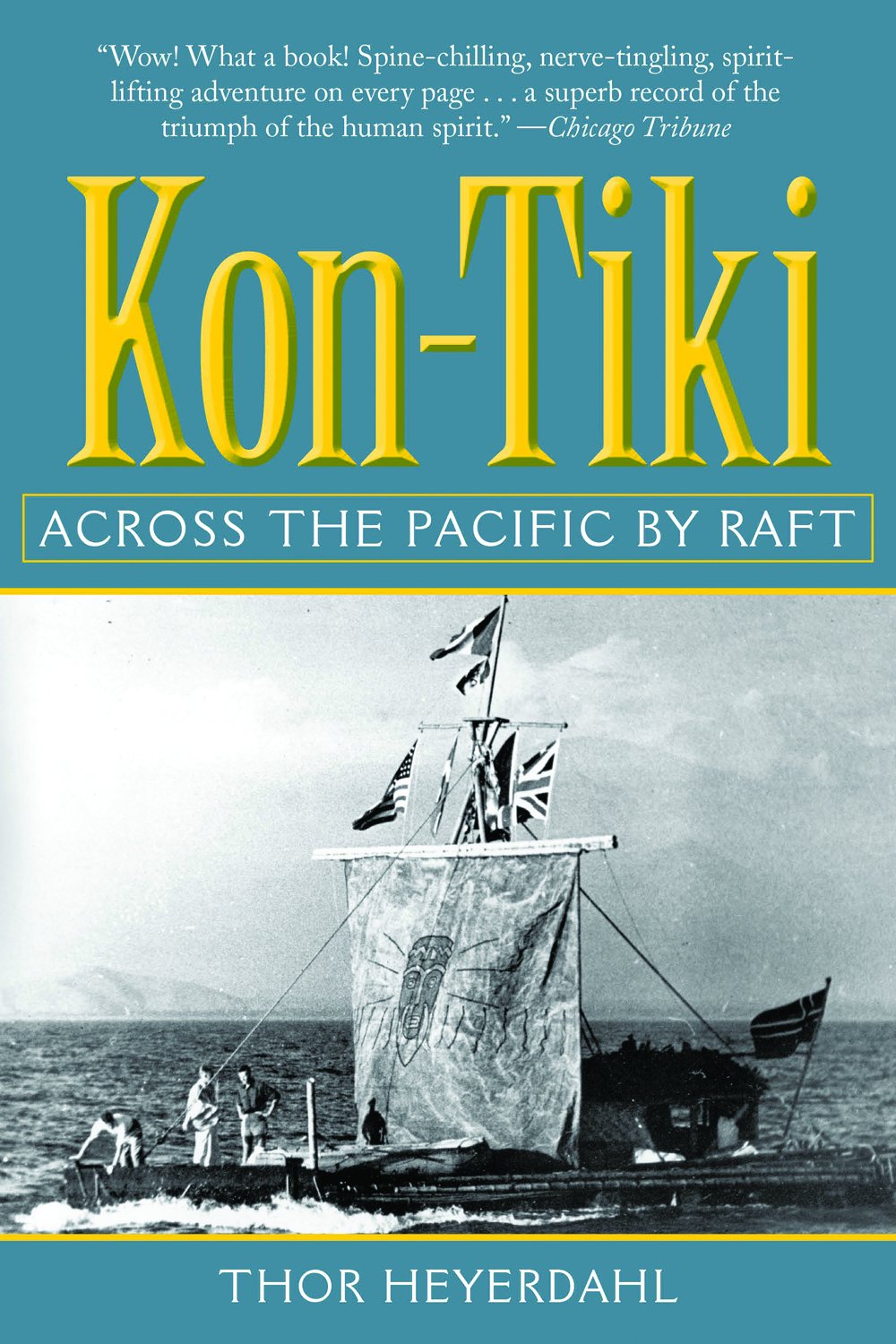

MY MIGRATION THEORY, AS SUCH, WAS NOT NECESSARILY proved by the successful outcome of the Kon-Tiki expedition. What we did prove was that the South American balsa raft possesses qualities not previously known to scientists of our time, and that the Pacific islands are located well inside the range of prehistoric craft from Peru. Primitive people are capable of undertaking immense voyages over the open ocean. The distance is not the determining factor in the case of oceanic migrations but whether the wind and the current have the same general course day and night, all the year round. The trade winds and the Equatorial Currents are turned westward by the rotation of the earth, and this rotation has never changed in all the history of mankind.

A THEORY

Retrospect -

The Old Man on Fatu Hiva

Wind and Current Hunting for Tiki

Who Peopled Polynesia?

Riddle of the South Seas

Theories and Facts

Legend of Kon-Tiki

and the Mysterious White Men

War Comes

A Theory

ONCE IN A WHILE YOU FIND YOURSELF IN AN ODD situation. You get into it by degrees and in the most natural way but, when you are right in the midst of it, you are suddenly astonished and ask yourself how in the world it all came about.

If, for example, you put to sea on a wooden raft with a parrot and five companions, it is inevitable that sooner or later you will wake up one morning out at sea, perhaps a little better rested than ordinarily, and begin to think about it.

On one such morning I sat writing in a dew-drenched logbook:

May 17. Norwegian Independence Day. Heavy sea. Fair wind. I am cook today and found seven flying fish on deck, one squid on the cabin roof, and one unknown fish in Torsteins sleeping bag....

Here the pencil stopped, and the same thought interjected itself: This is really a queer seventeenth of Mayindeed, taken all round, a most peculiar existence. How did it all begin? a

If I turned left, I had an unimpeded view of a vast blue sea with hissing waves, rolling by close at hand in an endless pursuit of an ever retreating horizon. If I turned right, I saw the inside of a shadowy cabin in which a bearded individual was lying on his back reading Goethe with his bare toes carefully dug into the latticework in the low bamboo roof of the crazy little cabin that was our common home.

Bengt, I said, pushing away the green parrot that wanted to perch on the logbook, can you tell me how the hell we came to be doing this?

Goethe sank down under the red-gold beard.

The devil I do; you know best yourself. It was your damned idea, but I think its grand.

He moved his toes three bars up and went on reading Goethe unperturbed. Outside the cabin three other fellows were working in the roasting sun on the bamboo deck. They were half-naked, brown-skinned, and bearded, with stripes of salt down their backs and looking as if they had never done anything else than float wooden rafts westward across the Pacific. Erik came crawling in through the opening with his sextant and a pile of papers.

98 46 west by 8 2 southa good days run since yesterday, chaps!

He took my pencil and drew a tiny circle on a chart which hung on the bamboo walla tiny circle at the end of a chain of nineteen circles that curved across from the port of Callao on the coast of Peru. Herman, Knut, and Torstein too came eagerly crowding in to see the new little circle that placed us a good 40 sea miles nearer the South Sea islands than the last in the chain.

Do you see, boys? said Herman proudly. That means were 850 sea miles from the coast of Peru.

And weve got another 3,500 to go to get to the nearest islands, Knut added cautiously.

And to be quite precise, said Torstein, were 15,000 feet above the bottom of the sea and a few fathoms below the moon.

So now we all knew exactly where we were, and I could go on speculating as to why. The parrot did not care; he only wanted to tug at the log. And the sea was just as round, just as sky-encircled, blue upon blue.

Perhaps the whole thing had begun the winter before, in the office of a New York museum. Or perhaps it had already begun ten years earlier, on a little island in the Marquesas group in the middle of the Pacific. Maybe we would land on the same island now, unless the northeast wind sent us farther south in the direction of Tahiti and the Tuamotu group. I could see the little island clearly in my minds eye, with its jagged rust-red mountains, the green jungle which flowed down their slopes toward the sea, and the slender palms that waited and waved along the shore. The island was called Fatu Hiva; there was no land between it and us where we lay drifting, but nevertheless it was thousands of sea miles away. I saw the narrow Ouia Valley, where it opened out toward the sea, and remembered so well how we sat there on the lonely beach and looked out over this same endless sea, evening after evening. I was accompanied by my wife then, not by bearded pirates as now. We were collecting all kinds of live creatures, and images and other relics of a dead culture.

I remembered very well one particular evening. The civilized world seemed incomprehensibly remote and unreal. We had lived on the island for nearly a year, the only white people there; we had of our own will forsaken the good things of civilization along with its evils. We lived in a hut we had built for ourselves, on piles under the palms down by the shore, and ate what the tropical woods and the Pacific had to offer us.

On that particular evening we sat, as so often before, down on the beach in the moonlight, with the sea in front of us. Wide awake and filled with the romance that surrounded us, we let no impression escape us. We filled our nostrils with an aroma of rank jungle and salt sea and heard the winds rustle in leaves and palm tops. At regular intervals all other noises were drowned by the great breakers that rolled straight in from the sea and rushed in foaming over the land till they were broken up into circles of froth among the shore boulders. There was a roaring and rustling and rumbling among millions of glistening stones, till all grew quiet again when the sea water had withdrawn to gather strength for a new attack on the invincible coast.

Its queer, said my wife, but there are never breakers like this on the other side of the island.

No, said I, but this is the windward side; theres always a sea running on this side.

We kept on sitting there and admiring the sea which, it seemed, was loath to give up demonstrating that here it came rolling in from eastward, eastward, eastward. It was the eternal east wind, the trade wind, which had disturbed the seas surface, dug it up, and rolled it forward, up over the eastern horizon and over here to the islands. Here the unbroken advance of the sea was finally shattered against cliffs and reefs, while the east wind simply rose above coast and woods and mountains and continued westward unhindered, from island to island, toward the sunset.

So had the ocean swells and the lofty clouds above them rolled up over the same eastern horizon since the morning of time. The first natives who reached these islands knew well enough that this was so, and so did the present islanders. The long-range ocean birds kept to the eastward on their daily fishing trips to be able to return with the eastern wind at night when the belly was full and the wings tired. Even trees and flowers were wholly dependent on the rain produced by the eastern winds, and all the vegetation grew accordingly. And we knew by ourselves, as we sat there, that far, far below that eastern horizon, where the clouds came up, lay the open coast of South America. There was nothing but 4,000 miles of open sea between.