Contents

To Ben Kozel and Scott Borthwick.

We all need friends to

accompany us on our journeys.

PROLOGUE

Day 9: September 21, 1999

I didnt expect to die of thirstcertainly not at twenty-seven. I knew it was a possibility, an inherent risk in any adventure, but I thought we had minimized our risk through careful planning, training, and a set of modest goals. Today, I was not so sure.

If you looked around, you saw packed dirt, sand, and rock everywhere. It was lunar and we might as well have been on the dark side of the moon. We had no way to summon help. No one knew precisely where we were in Peru, and no one would report us missing for weeksif then. Our journey across South America was supposed to take six months, and no one expected us to check in. It was difficult to believe that, within two weeks, we found ourselves in such a predicament.

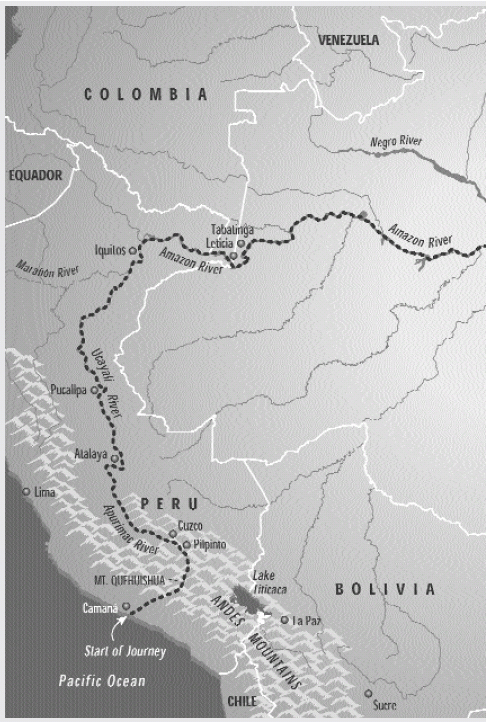

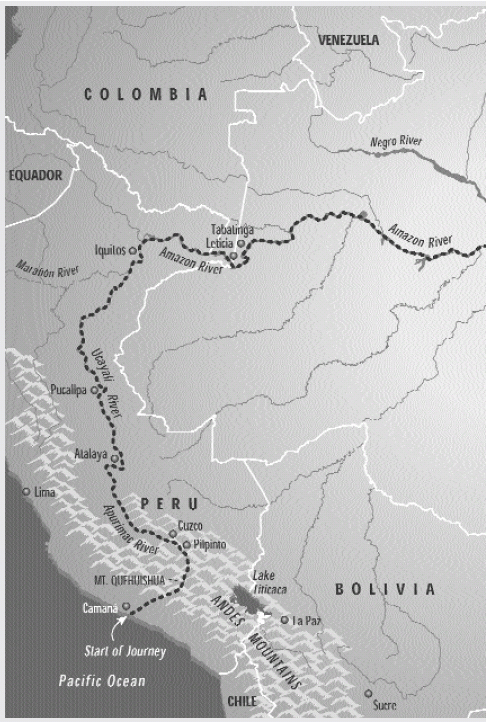

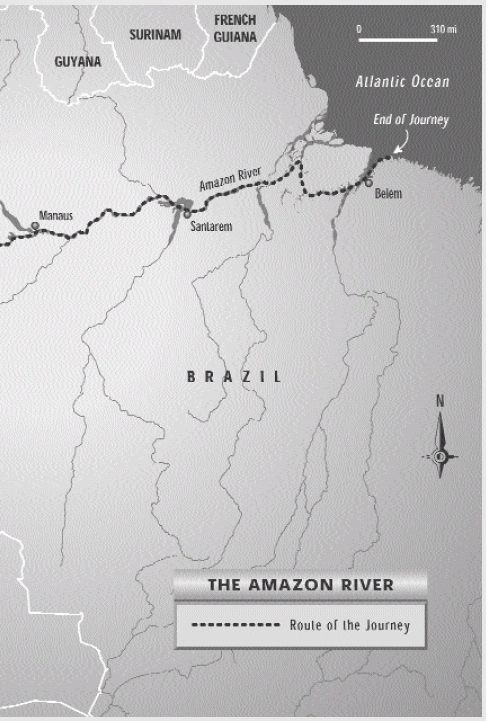

We began our trek from a soiled Pacific Ocean beach, hiking up the lush Ro Caman and Ro Majes river valleys as far as we could. Leaving that narrow strip of water and life behind, we hiked across a slightly tilted tabletop plateau on the western shoulder of the Andes. At first, the topography of the upper-highland desert was a vast plain strewn with boulders. Thousands of large, sienna-colored rocks littered the landscape. Gradually they became less numerous, until now they could be seen peeking out from the folds of the land or balancing on the larger ledges. It was as though someone had spilled a bag of marbles up ahead and most of the alleys had rolled down the incline, except those that hit a fissure, an outcropping, or a ledge.

The landscape was a spectrum of sandy tones and hues, with the horizon a gauzy pale blue above the jagged line of the hilltops. By one oclock the sun was white hot. We were walking across an open-air ovena constant dry heat accompanied by an incessant wind that scoured the land. There was no life but the occasional cactus. We were three gringos in a foreign desert, slowly dying. The sand would preserve us perfectly if we collapsedjust as it had the many centuries-old mummies found here.

I decided to abandon my pack because it was too much to carry as I got weaker. Scott and Ben dumped theirs, too. Appearances be damned, we were in serious trouble. We probably would not survive the two-and-a-half-day trek back to the Majes Valley without water. Our only chance was to push on and trust the dated maps.

We rested, briefly. I sat, my muscles throbbing with pain, yearning for a drink. We didnt talk because it took too much effort. Besides, our tongues were swollen by dehydration. I thought about our prospects and how ill-prepared we seemed to be. It was almost comical: Don Quixote saw reality more clearly. I would have laughed, but I was afraid I would crack my lips. I decided to save the mirth for later.

For more than a year I had thought about crossing South America from one coast to the other, mostly by running the Amazon in a whitewater raft. I was living in southwestern Alberta, at the foot of the Rocky Mountains, chopping wood in a forest of burned pine to pay the rent. Snow swirled around my feet when it hit me: Explore the Amazon! Go explore the Amazon. Yeah, thats the ticket. In the middle of a North American winter, thoughts of a hot, steamy jungle warmed my soul, and the prospect of riding rapids from the Andes to the Atlantic fired my imagination. Yippee-kiyay, cowboy!

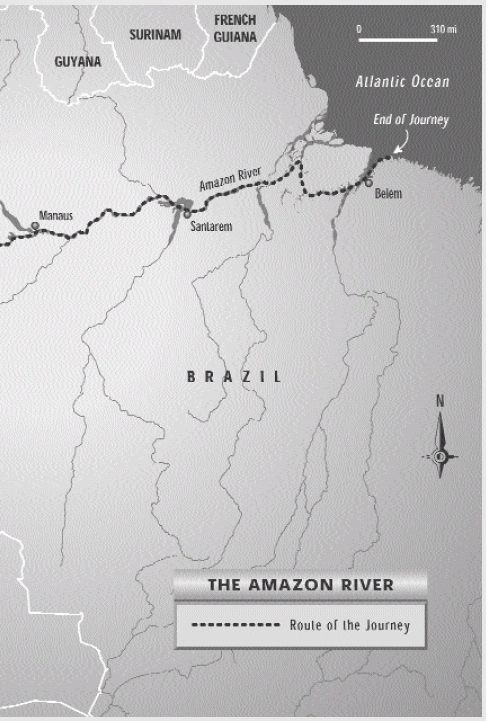

The more I thought about it, the more alluring an Amazon adventure became. Almost no one had gone down the entire river and no one had rafted it from start to finish. I wanted to be the first.

This was the initial leg of the trip, a relatively short hike from the Pacific Ocean into the mountains. We wanted to reach the continental divide and the source of the Amazon River, the planets most mystical waterway. We planned to extreme raft the Amazon, from the headwaters to the mouth on the Atlantic Ocean.

Oh, how the road to hell is paved with good intentions! Here we were in the high desert, the prospect of even seeing the source of the Amazon seemingly more remote than when I was in Canada. Scott, Ben, and I were parched, likely lost, and beginning to understand from the soles of our burning feet to the tops of our scorched heads that we had been very foolish. I looked around. An inexorable sun singed our retinas as it crossed the barren landscape like a blowtorch caramelizing sugar. We were in imminent danger of becoming condor chow.

Western Peru is a narrow, desolate, coastal desert lying at the base of the Andesamong the planets tallest mountains. We knew thatits in all the books. The southern hemispheric weather patterns are the reverse of North Americas, so the rains fall on the eastern side of the mountains, not the Pacific side. Western Peru is in a rain shadow, parched and nearly lifeless. We knew that too. Yet here we were dying of heat prostration.

I envisioned the worst:

CUZCO, PERU (AP) The bodies of Scott Colin Angus, 27, of Canmore, Alta., Ben Kozel, 26, of Australia, and Scott Borthwick, 23, of South Africa, were recovered yesterday from a barren, isolated area about 200 miles southwest of this fabled Inca city. Ironically, they died of thirst on their way to raft the worlds second-longest fresh-water river from its source to its mouth.

This part of the trip was supposed to be a cakewalk. The Amazon almost bisects the continent. It starts only about a hundred miles from the west coast and there is some evidence that in prehistory it might have emptied into the Pacific Ocean. As the two tectonic plates under the continent collided, they caused enough geological dislocation to reverse the drainage pattern. Our plan was to start at the coastal town of Caman, hike to the continental divide, and ride the Apurimac and the Amazon to the Atlantic Ocean. Our focus had been entirely on the river: it was extreme whitewater for much of the journey, a courage-testing descent from 17,000 feet in the Andes to the 5,000-foot level of the Upper Amazon basin. We had not put much thought into this hiking segment of the journey.

We arrived in Peru two weeks ago, flying first to the old Inca capital, Cuzco, where we deposited our river gear with the South American Explorers Club. The equipment consisted primarily of our 13-foot self-bailing raft, five paddles, tent, back-up butane stove, throw-bags, four 115-quart dry-bags, smaller personal dry-bags, water filter, climbing gear, ropes, repair kit, cam straps, two pumps, water containers, cooking utensils, video tapes, and fishing gear. With the gear in storage, we headed back to the coast by bus to make the climb into the Andes on foot.

We started full of assurance. I had already taken off alone on a tiny sailboat to challenge the mighty Pacific. It wasnt an ego trip, and on my return I hadnt gone around bragging about my feats of derring-do. Yet, though I didnt consider the things I had done particularly special, I knew I was different from most people. I found opportunities where others saw obstacles. Daydreaming is my favourite activity. I regularly get lost in reveriefantastic scenarios unfolding in my mind with such clarity that they rival reality. These dreams have led me to travel.

The Amazon evoked such strong feelings for me that I thought it was calling me. This was an adventure I felt compelled to undertake. Im a doer, not a couch potato or an Internet geek. I decided to go down the Amazon not because the journey would be cited in some book of records, and certainly not to make people respect me or look up to me. I decided to extreme raft the Amazon because I wanted todesperately. Heck, I wanted to have some fun, and everything I read told me this would be the adventure of a lifetime. Besides, what better way is there to learn about the world, yourself, your friends, and your character?

Next page