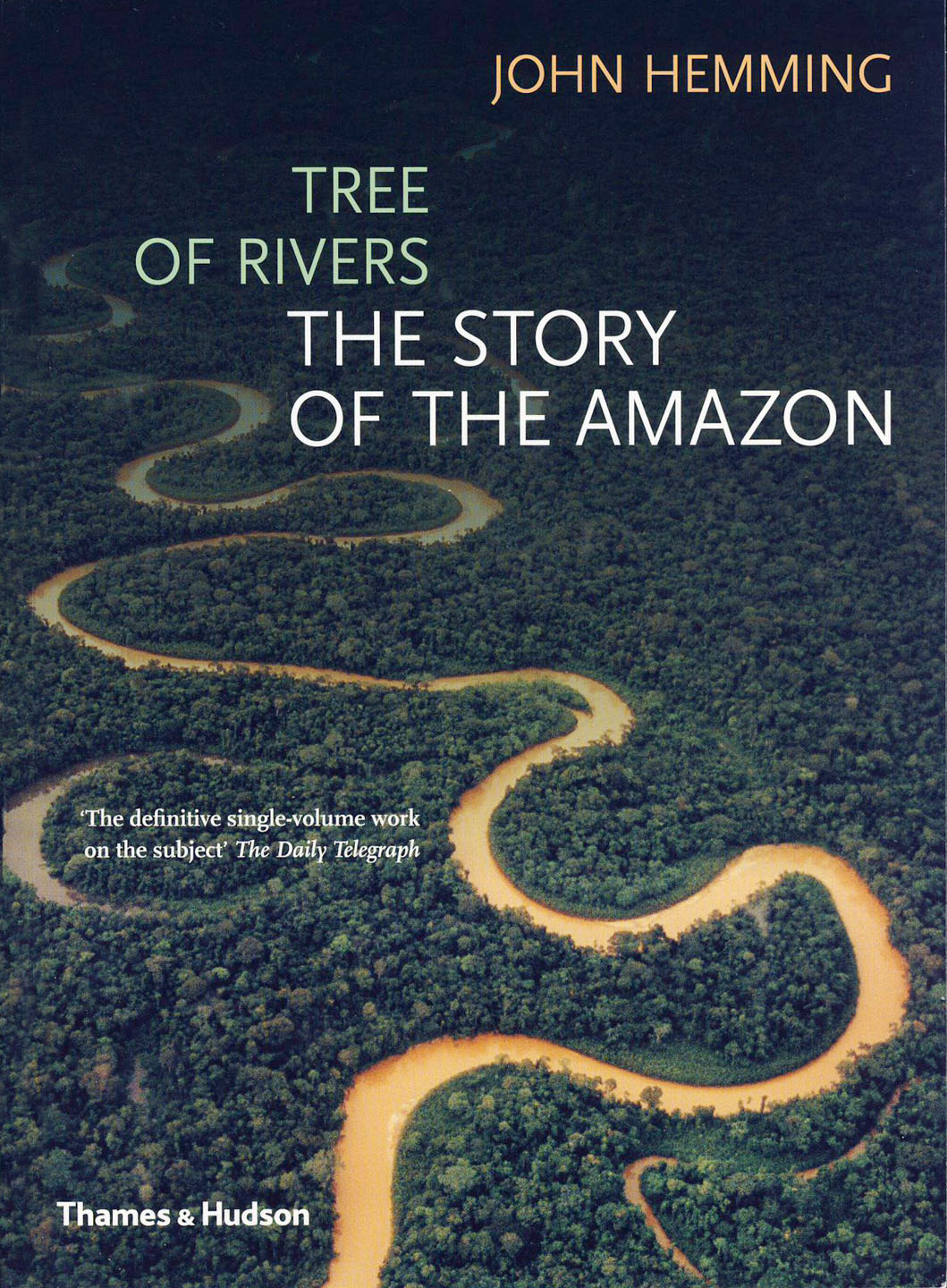

JOHN HEMMING

Tree of Rivers

The Story of the Amazon

John Hemming

is an expert on the Amazon, having visited over forty indigenous tribes and been on many research expeditions, including explorations of totally unknown territories. His previous books include the prize-winning The Conquest of the Incas and a trilogy on the history of Brazilian Indians. He was for 21 years Director of the Royal Geographical Society in London.

Other titles by John Hemming published by Thames & Hudson include:

Monuments of the Incas

Other titles of interest published by Thames & Hudson include:

The Great Naturalists

The Great Explorers

The Seventy Great Mysteries of the Natural World: Unlocking the Secrets of Our Planet

The Earth from the Air

Latin Spirit 365 Days: The Wisdom, Landscape and Peoples of Latin America

Sebastio Salgado: An Uncertain Grace

See our websites:

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Contents

-->

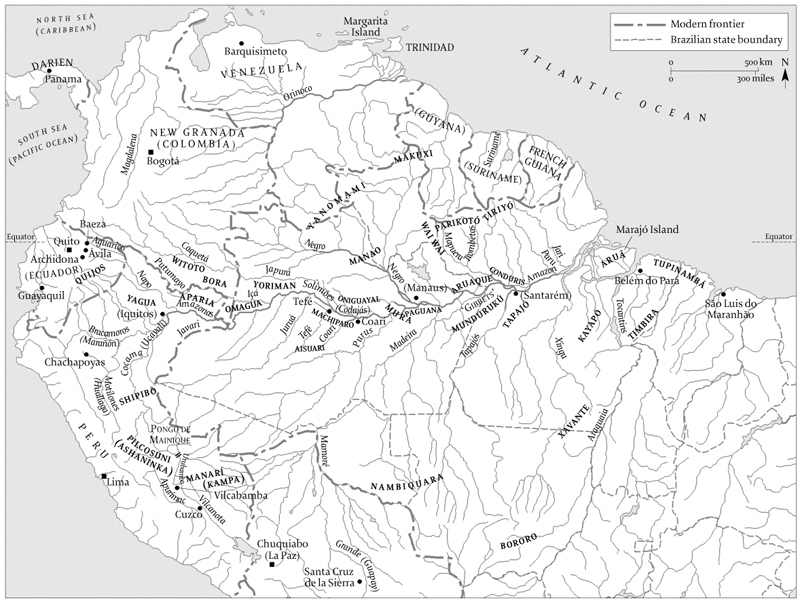

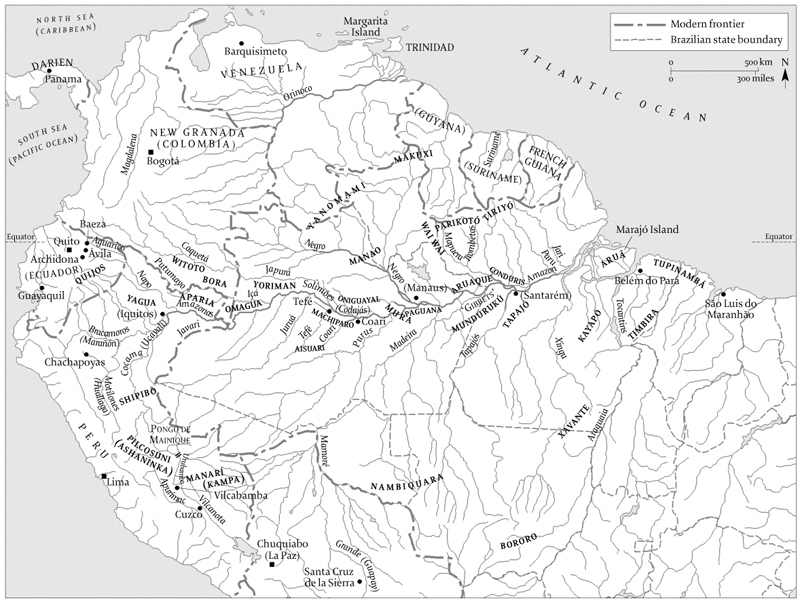

First descents of the Amazon River

A black-water river in Venezuelan Amazonia, where the lack of sediment from ancient rocks and the tannin from decaying vegetation make waters as black as coffee. Forests are at their most exuberant on river banks, because of the sun and water. (Photo John Hemming)

Palm trees are wonderfully useful to man, from the earliest foragers to present-day riverbankers. Graceful Buriti palms (Mauritia flexuosa) soar to 30 metres (100 feet), and supply nutritious red fruits, fronds for roofing, fibres for baskets and hammocks, and trunks for beams. (Photo Dudu Tresca)

This caterpillar of a hawk moth (Pseudosphinx tetrio) is an example of Batesian mimicry, named after the nineteenth-century naturalist Henry Walter Bates. A predator thinks that such a gaudily coloured insect must be poisonous, so this edible caterpillars only defence is to mimic such ostentation. (Photo James Ratter)

Most creatures in a tropical forest are high in the canopy, or nocturnal, or brilliantly camouflaged, like this long-horned grasshopper (Tettigoniidae family) mimicking a leaf and twig. (Photo William Milliken)

Most of Amazonias hundreds of species of snake are harmless to man, but not these deadly rattlesnakes (Crotalus terrificus). They hunt by night, attracted by the warmth of their prey. (Photo John Hemming)

White-lipped peccary (Tayassu pecari) move in large packs, scouring the forest floor for nuts and roots. If threatened, these powerful animals attack fearlessly and are one of the few animals that can hurt humans. (Photo Haroldo Palo)

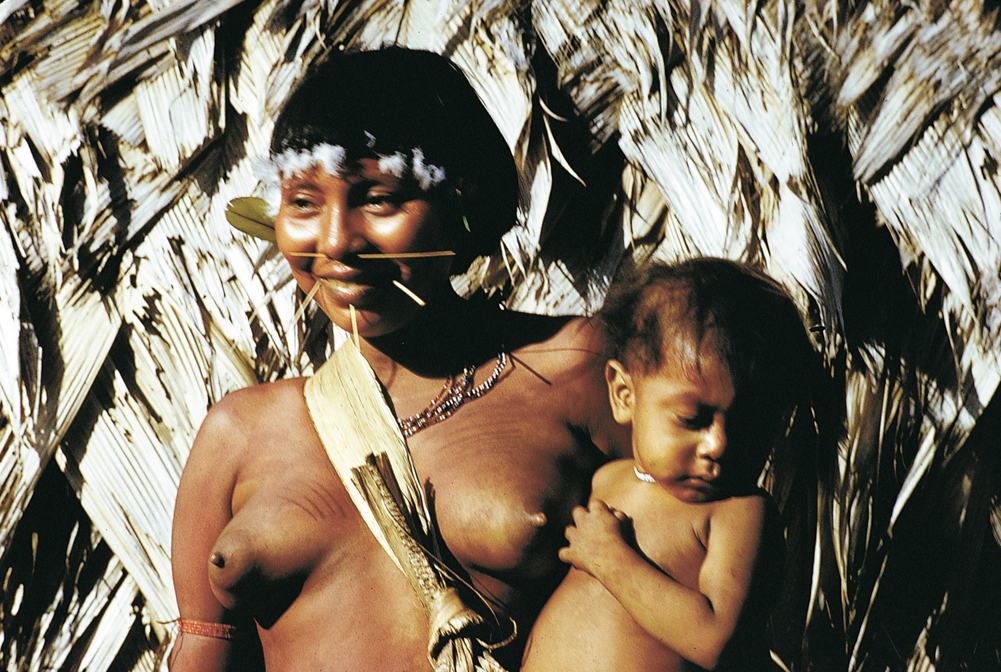

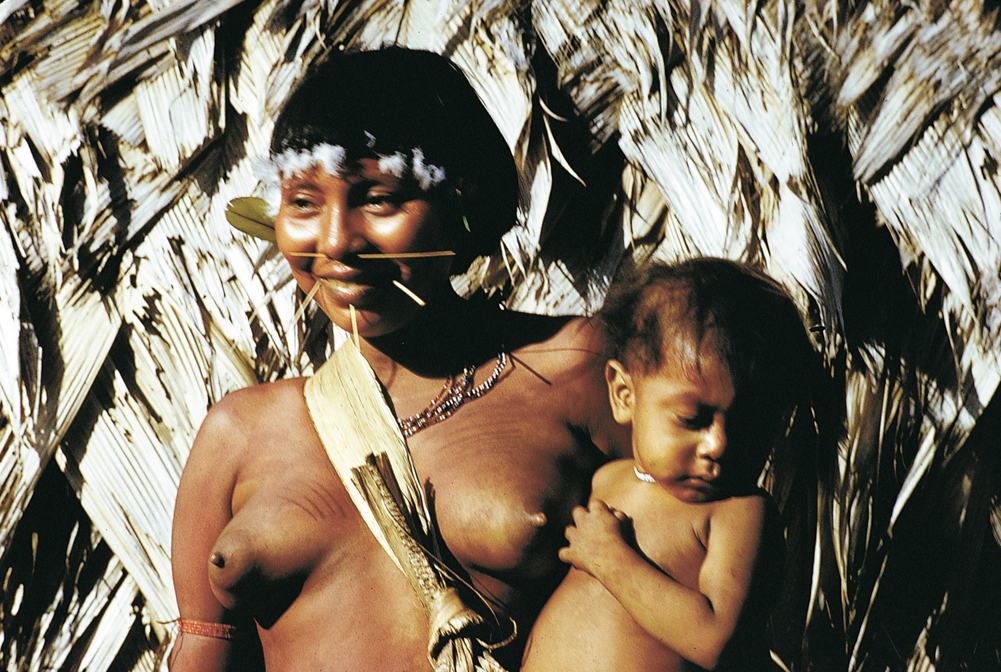

The largest indigenous nation, the Yanomami, live in forested hills between Brazil and Venezuela. Here a mother decorates herself with red annatto dye, feathers gummed to her hairline, and palm-spine feline whiskers. (Photo John Hemming)

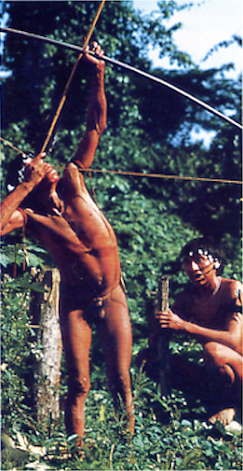

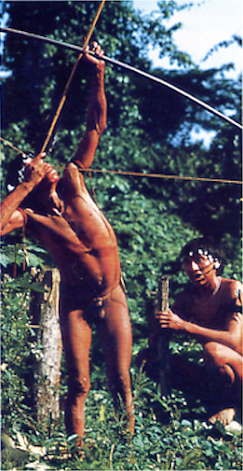

Yanomami archers use immensely powerful bows and two-metre-long (612-foot) arrows, often tipped with curare poison and with different points for different types of game. They carry chewing tobacco in a wad in their lower lips. (Photo John Hemming)

Kayap women of central Brazil dye their skin with black genipapo dye, for decoration and as protection against insects, and they ritually shave their own and their childrens frontal hair. (Photo John Hemming)

to take home as slaves. This was an ominous portent of misery in store for the native peoples.

Yez Pinzns ships were only several times larger than the dugout canoes of the indigenous people whom the Spaniards thought to be Indians from India. What must have surprised the few natives who saw the ships was their being covered by decks, having men living on board, with many ropes thicker than the Indians own cord, and above all their propulsion by canvas sails. In the later mythology of another tribe, the arrival of the first white men in a flotilla of sailing boats was depicted as a swarm of flying ants. Even more curious was the way in which the sailors covered their bodies in a material cloth. There was ugly hair growing on their faces, and this was sometimes of freakish colours other than black. (Native South Americans have practically no body hair, and most pluck any that does appear on their skins; and their hair is invariably black.)

The most sensational impact was caused by the strangers metal tools. When the Portuguese landed further south in Brazil a few months after Yez Pinzn, they made a cross to celebrate the first mass in this new land. One of them, He was absolutely right. This was the intense thrill of people first witnessing the cutting-power of metal tools. It was a technological miracle in a forested world where mens most wearisome task was felling trees to create garden clearings. For the next five centuries, from 1500 to the present day, metal blades from knives and machetes to axes and saws have been the currency of contact with every isolated tribe. Such tools are an irresistible lure. Again and again, after contact has been made, it is learned that the indigenous people had seen blades and were desperate to acquire them, either by raiding or coming to terms with whites.

The next adventurer to see the Amazon may have been the Florentine Amerigo Vespucci. As the agent in Seville of the Medici princes, Vespucci in 1499 joined some Spaniards to obtain a royal licence to cross the Atlantic. But when the squadron reached South America it divided and the Italian took two caravels in a southerly direction. He also investigated the mouth of a great muddy river, but its forested banks prevented a landing. Vespucci then sailed southeastwards before being driven back by adverse currents. It is impossible to tell how far south he sailed since Vespucci was a hopeless surveyor: the coordinates he gave for the Atlantic coast of Brazil would have located it far out in the Pacific. His fame stems from a voyage three years later, when he was a passenger on a Portuguese flotilla. He spent three weeks among Brazilian Indians and sent his Medici master an enthusiastic but rather inaccurate account of the wonders he had seen. Most such reports were kept secret by European rulers, but Vespuccis letter was published, rapidly translated into several languages, and became an instant bestseller by the standards of its day. He was the first to write that this was a new world rather than a mere island. Such was the power of the new printing press that a map-maker in Lorraine wrote a version of his first name America on a map showing the Mundus Novus of the new discoveries. The name stuck. So two continents are named after an undistinguished sailor, an inaccurate navigator, and a boastful chronicler. Amerigo Vespucci must be the patron saint of all travel-writers.

Next page