HENRY HEMMING is the author of four works of non-fictionTogether, In Search of the English Eccentric, Misadventure in the Middle East, and a monograph on the artist Abdulnasser Gharemand has coauthored the visual books Edge of Arabia and Offscreen. He has written for The Sunday Times, Daily Telegraph, Daily Mail, The Times, The Economist, FT Magazine, and The Washington Post and has given interviews on Radio 4s Today Programme and NBCs Today Show and spoken at schools, festivals, and companies including RDF Media, The RSA, Science Museum, Frontline Club, The School of Life, Port Eliot Literary Festival, and Canvas8, where he is a Thought Leader. He lives in London with his wife and daughter.

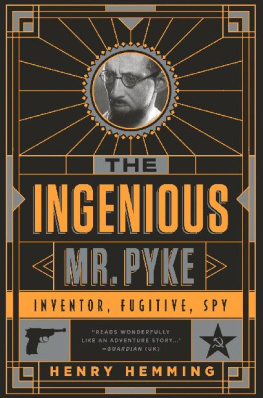

I still remember the thrill of being shown into the dusty attic, in south London, which contained almost all of Geoffrey Pykes papers. It was 2008, and by my side was Pykes daughter-in-law, Janet. The sight before me was a biographers dream papers which had not been touched for decades gathered together in bulging bin liners, wasp-strewn trunks and khaki folders fastened long ago with pins. Not only did Geoffrey Pyke write prolifically but he tried to keep everything he put down on paper. My greatest debt in writing this book is to Janet Pyke and her family for allowing me to see these papers and for providing assistance and encouragement over the last six years.

Just months after I decided to write this life of Pyke, MI5 released almost all of its papers on him to the National Archives in Kew. I am grateful both to the Security Service for choosing to do so at this particular moment and to the staff at the National Archives, particularly Ed Hampshire. Id also like to acknowledge the assistance I received at the British Library, the Lambeth Archive, Nuffield College Library, the new defunct newspaper library at Colindale, Cambridge University Library, the Archive Centre at Kings College, Cambridge, the National Archives and Library of Congress in Washington DC and the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library at Hyde Park, New York State. Michael Meredith at Eton College Library, Glyn Hughes at the National Meteorological Archive, Catherine Wise at the Cambridge Union Society, John Entwistle at the Reuters Archive, Cindy Tsegmid and Lucy Arnold at the Leeds University Archive, Dr G. E. Edwards at Pembroke College, Steven Leclair at the National Research Council Canada in Ottawa and Katharine Thomson at the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge were equally helpful.

Further assistance, for which I am indebted, came from Bernd Barth-Rainer, Peter Morris, Georgina Ferry, Michael Weatherburn, Jeremy Lewis, Paul Collins, Jared Bond, Jonathan Ray, Janet Sayers, Kevin Morgan, Gordon Corera, Thomas Rnkel, Reinhard Mller, Charles Faringdon, John Monson, Amir Sam, John Betteridge, Philip Womack, Lindsay Merriman, Hugo Macpherson, Sarah and Tom Carter, Robin Lane Fox, George Weidenfeld, Artemis Cooper, John Julius Norwich, Leonora Lichfield, Harriet Crawley, Dickie Wallis, Cutler Cook, Alexander Kan, Jeremy Bigwood, Andrew Lownie, Nigel West, Boris Jardine, Nicolas Smith, Karen Ganilsy, Stephen Raleigh, Anthony Hentschel and Charles Leadbeater.

Jonathan Conway showed tenacity and skill in helping to shape the outline of this book. Trevor Dolby at Preface has been hugely supportive throughout and great fun to work with. Will Sulkin was an extraordinarily thoughtful editor. John Sugar and Rose Tremlett at Preface have both been immensely helpful. For this American edition, Im enormously grateful to everyone at PublicAffairs, including Melissa Raymond, Melissa Veronesi, and in particular, my editor Ben Adams. Thanks also to my dad, for his feedback, and to Bea, my sister, to whom this book is dedicated and who has been, from the start, full of imaginative advice.

Finally my love and thanks to the two women in my life, Helena and our daughter Matilda, the latter for splashing me each evening at bathtime, the former for her unending love, silliness and unconditional encouragement. I cant imagine doing any of this without you you make the whole thing worthwhile.

In what follows direct speech is taken verbatim from either contemporary accounts or memoirs.

PublicAffairs is a publishing house founded in 1997. It is a tribute to the standards, values, and flair of three persons who have served as mentors to countless reporters, writers, editors, and book people of all kinds, including me.

I. F. STONE, proprietor of I. F. Stones Weekly, combined a commitment to the First Amendment with entrepreneurial zeal and reporting skill and became one of the great independent journalists in American history. At the age of eighty, Izzy published The Trial of Socrates, which was a national bestseller. He wrote the book after he taught himself ancient Greek.

BENJAMIN C. BRADLEE was for nearly thirty years the charismatic editorial leader of The Washington Post. It was Ben who gave the Post the range and courage to pursue such historic issues as Watergate. He supported his reporters with a tenacity that made them fearless and it is no accident that so many became authors of influential, best-selling books.

ROBERT L. BERNSTEIN, the chief executive of Random House for more than a quarter century, guided one of the nations premier publishing houses. Bob was personally responsible for many books of political dissent and argument that challenged tyranny around the globe. He is also the founder and longtime chair of Human Rights Watch, one of the most respected human rights organizations in the world.

For fifty years, the banner of Public Affairs Press was carried by its owner Morris B. Schnapper, who published Gandhi, Nasser, Toynbee, Truman, and about 1,500 other authors. In 1983, Schnapper was described by The Washington Post as a redoubtable gadfly. His legacy will endure in the books to come.

Peter Osnos, Founder and Editor-at-Large

On 1 September 1914 Geoffrey Pyke left the offices of one of the countrys best-selling newspapers in something of a daze. What he had just suggested to the News Editor of the Daily Chronicle was so outlandish, so apparently silly, that he had given little thought to the possibility that it might be taken up. Now, as he made his way through the hurly-burly of Fleet Street, with bodies brushing past and the hum of horse manure buffeting up around him, he broke into a sweat. The thought jammed in his head was simple enough: that as a result of the conversation which had just finished he might be taken outside a foreign jail before the end of the month and shot. Gazing up at the soot-streaked palaces on either side of him, buildings which no longer impressed him as they had done earlier, Pyke wondered if he had made a terrible mistake.

It had begun two months earlier, in July 1914, soon after he had finished his second year at Cambridge where his abilities made him conspicuous and he was thought to be extremely clever. Pyke was taller than most and gangly, with a mat of dark hair set above a playful expression, someone who thrived under pressure and exuded the hard-won confidence of a boy who had been bullied at school before blossoming at university.

Next page

![Nicholas Rankin [Nicholas Rankin] - Churchills Wizards](/uploads/posts/book/56578/thumbs/nicholas-rankin-nicholas-rankin-churchill-s.jpg)