The First Special Service Force was made up of three regiments: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd. Each was made up of two battalions of three companies. Since the companies in each regiment were numbered one through six, Force men identified them by company number-regiment number. This book employs this system. Hence, the three companies discussed in detail1st Company-1st Regiment, 1st Company-2nd Regiment, and 3rd Company-3rd Regimentare sometimes mentioned in the following pages as 1-1, 1-2, and 3-3.

Les hommes valeureux le sont au premier coup.

PROLOGUE

I n June 2004, I travelled to Rome as a journalist to cover the sixtieth anniversary of the citys liberation by Allied armies during the Second World War. At first the assignment seemed little more than a pleasant excuse to visit Italy in early summer. The articles I would be writing would most certainly be relegated to the features sections of newspapers, and then ignored, I assumed, when the commemorations marking the Normandy landings began in France. Sixty years later, there was still no bigger story than D-Day.

In Rome, I made arrangements to meet with a group of Canadian and American veterans who had fought together in a single unit, and were the first soldiers to enter the capital in the wake of the retreating German armies. Bill Story, the executive director of the units veterans association, had arranged for me to join a reunion tour, and visit the old battlefields with the former soldiers and their families. This was my first face-to-face meeting with the men of First Special Service Force (FSSF), or, as the Germans called them, the Black Devils. And from the beginning, I was amazed.

I had heard of these men. As a kid I saw the movie The Devils Brigade, Hollywoods exciting if distorted interpretation of the unit and its history. I had spoken to veterans over the phone, and even written one or two commemorative articles about their exploits. At first I was interested in this unit because it had been made up of Canadians and Americans who served under a single command and wore the same uniforms: the only time in the history of both Canada and the U.S. that such a military partnership has happened. In addition, the First Special Service Force was credited with being one of the first of the worlds special operations units, and I was intrigued that Canada was a pioneer in this type of warfare.

Not very many people in this world get a chance to start something, one veteran told me. This is true, and in this sense the veterans of the FSSF hold a unique place in military history. They helped develop a revolutionary mode of warfare that is being fought on the front lines of todays struggle against international terrorism.

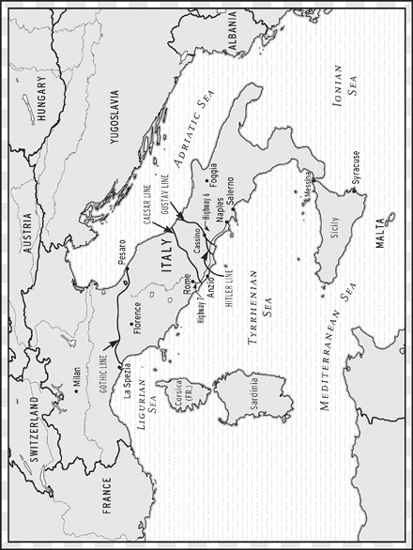

In obscure Second World War battlefields such as Monte la Difensa, Monte Majo, and Anzio, these men, who numbered fewer than two thousand, changed the course of the war in Italy. And in the process they tallied an unprecedented record of accomplishment that I found literally stunning when I first heard it mentioned in Daring to Die, a television documentary written and co-directed by a grandson of an FSSF veteran. In only a year of combat, for every Force man who fell in battle, the unit killed 25 of the enemy; for every Force man taken prisoner, the FSSF captured 235 of the enemy.

Their campaign history was just as impressive. The FSSFs first battle and victory in December 1943 on the central Italian peak of Monte la Difensa broke a month-long stalemate on the Winter Line that had halted the advance of the entire U.S. Fifth Army. Later, at the Anzio beachhead, the Force, depleted by casualties to a mere 68 officers and 1,165 enlisted men, did the work of a division more than ten times its size, guarding thirteen kilometres of the front line for almost one hundred days.

These accomplishments went largely unnoticed, for two reasons: first, the Force was considered a classified weapon, and its victories often went unpublicized; and second, the Pyrrhic Allied victories of the Italian war tended to obscure the units contributions. The Forces feat on Monte la Difensa was immediately eclipsed by the agonizing Allied campaign to break through the Gustav Line at Cassino; their robust defence of the Anzio beachhead was overshadowed by the fact that the Anzio operation itself was a strategic failure; and their role as the first liberators of Rome was forgotten amid the deafening commotion of the invasion of Normandy two days later. The Force endured tremendous losses, but even this suffering became obscured. After their first battle the Force endured a 30 percent casualty rate; after their first six weeks in combat, their casualty rate rose to 60 percent. This ratio was abnormally high, but because of the Forces small size its losses represented 1,400 killed, wounded, and missing mena number that may seem small when set beside the 25,264 casualties Canada withstood in the Italian war.

But despite all the things that set the FSSF apart, in the end it makes most sense to see them as exemplars of the resolve and courage of the Allied war effort, and in particular of the Canadian contribution to it. As it had done in the First World War, Canada fought the Second with the punching power of a much larger nation, fielding whole armies in two theatres of the war, and earning a reputation among friends and enemies alike for doggedness and ferocity. As had been the case in the trenches of France and Belgium in the Great War, the Germans dreaded squaring off against Canadian regiments the second time war engulfed Europe. And long after the guns have fallen silent, the echoes of battle resonate through our culture. Though the Canadian victory at Vimy Ridge in 1917 did not break the stalemate of the Western front, the gallantry of Canadian troops under Canadian command, and their success where others had failed, marked that battle as a moment when their nation could take its place as an equal at the councils of the great powers. The achievements of the Canadian armies against Hitlers forces, to say nothing of the Royal Canadian Navy guarding the Atlantic shipping lanes, or the Royal Canadian Air Force contesting the skies against the Luftwaffe, marked Canada as a country willing to match deeds to words in a moment of historical crisis. It is in this light that we should see the Canadians of the FSSF. They were Canadas best, teamed up with the best of the United States. Fighting at each others sides, they were nearly invincible.

Sadly, the Second World War outlived the unit and nearly five hundred of its soldiers. But as intriguing as this history is, the moment I met the men themselves I became fascinated by the Force solely because of them. As the name of their outfit implied, they were special, and the passage of sixty years has not diminished this. In Rome, I met Herb Peppard, a vital, youthful octogenarian from Nova Scotia, who had the health of a 55-year-old, entertained his fellow veterans with old wartime songs still at the tip of his tongue, and did not once mention the U.S. Silver Star he had earned for bravery. I met William Sam Magee, another Silver Star-decorated vet and an energetic Ontarian who devoted his retirement to visiting schools and educating young Canadians about his experience of the Second World War. I met General Ed Thomas, the distinguished Southern gentleman who had organized the tour. I met an equally gentlemanly veteran from St. Louis, Missouri, named Sam Finn, who told me a fascinating tale of how he marked the liberation of Rome by reclining in the chair of Fascist leader Benito Mussolini and placing a pair of dirty boots on the dictators desk. Despite the grim business they had returned to commemorate, veterans like Lloyd Dunlop and Hector MacInnis, both from Nova Scotia; Charlie Mann and Jack Callowhill, of Ontario; Eugene Gutierrez of McAllen, Texas; and Arthur Pottle of Saint John, New Brunswick were conspicuous for their laughter and optimism.