Bibliography

Bosi, Alfredo. Historia concisa da literatura brasileira. So Paulo: Cultrix, 1970.

Carvajal, Fray Gaspar de. 1992. Relacin del nuevo descubrimiento del Rio Grande de las amazonas. Quito: Comisin Nacional Permanente de Conmemoraciones Cvicas/Museo Antropolgico del Banco Central de Guayaquil.

Cunha, Euclides da. Obra completa, Vol. 1. Rio: Aguilar, 1966.

. Um paraso perdido: Reunio dos ensaios amaznicos. Edited by Hildon Rocha. Rio: Vozes, 1976.

. Rebellion in the Backlands [Os Sertes]. Translated by Samuel Putnam. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1944.

Freyre, Gilberto. Euclides da Cunha. Revelador da realidade brasileira. In Euclides da Cunha, Obra completa, 1:17-31. Rio: Aguilar, 1966.

Hardman, Francisco Foot. A vingana da Hilia: Os sertes amaznicos de Euclides. Revista Tempo Brasileiro 144 (2001): 29-61. Special number: Repensando o Brasil com Euclides da Cunha.

Lauria, Mrcio Jos. Judas-Ahsverus. In Enciclopdia de estudos Euclidianos. Vol. 1. Jundia: Jundi, 1982.

Lima, Luiz Costa. Os Sertes: Cincia ou literatura? Revista Tempo Brasileiro 144 (2001). Special number: Repensando o Brasil com Euclides da Cunha.

. Terra Incgnita: a construo de os sertes. Rio: Civilizao Brasileira, 1997.

Magalhes, Jos Vieira Couto de. O Selvagem. Rio: Magalhes, 1913.

Rodrigues, Joo Barbosa. Poranduba amazonense ou kochyma uara porandub: 1872-1887. Rio: Leuzinger, 1890.

Rosaldo, Renato. Culture and Truth. The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston: Beacon, 1993.

Stokes, Charles. The Acre Revolutions, 1899-1903: A Study in Brazilian Expansionism. Ph.D. diss., Tulane University, 1974.

Stradelli, Ermanno. La leggenda delljurupary e outras lendas amaznicas. Caderno 4. So Paulo: Instituto Cultural Italo-Brasileiro, 1964.

Tocantins, Leandro. Euclides da Cunha e o paraso perdido. Rio: Civilizao Brasileira, 1978.

General Impressions

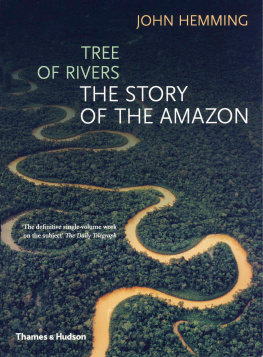

Rather than admiration and enthusiasm, what usually comes over someone beholding the Amazon at the point where the Tajapurus vibrant confusion flows full into the great river is a sense of disillusionment. To be sure, the sheer volume of water is unmatched and therefore capable of inducing that wonderment of which Wallace speaks. But since, from early on in life, each of us has drawn an ideal Amazonia in our minds thanks to the remarkably lyrical pages left us by the countless travelers, from Humboldt down to today, who have contemplated the prodigious hylean rain forest with almost religious awe, we experience a common psychological reaction when we come face to face with the real Amazon: we see it as somehow lacking with respect to the subjective image we have long held of it. Beyond that, as a strictly artistic phenomenonthat is, as a place on earth overflowing with images susceptible of being harmoniously fused into an awe-inspiring synthetic senseit is decidedly inferior to countless other sites in our own country. In this regard, the entire Amazonian region cannot match, for example, the stretch of our coastline that runs from Cabo Frio to Ponta de Munduba.

It is, nonetheless, doubtless the greatest sight in the land. That sight, however, is one restricted to the horizontal plane, for, much like the last remnants of an enormous, broken frame, the sandstone Monte Alegre range and the granite mountains of the Guianas now rise so little as to provide but a scant touch of relief on one side. And because of this lack of the vertical dimension, essential to imparting a sense of life to a landscape, within a few hours the observer tires in the face of an unbearable monotony and begins to notice that their gaze is less and less frequently directed to that endless horizon as empty and undefined as that of the sea.

The overwhelming impression I conceivedperhaps corresponding to a positive truthis this: humankind is still an impertinent interloper here. We have arrived uninvited and unprepared for, while nature was still in the process of setting up this vast, magnificent salon. Here we encounter disorder on a lavish scale the rivers are still not fixed in their courses. They seem to search vainly for equilibrium by wandering off aimlessly in unstable meanders that curve into the form of lakes called sacados with isthmuses that repeatedly break down and recombine in the futile creation of islands and lakes of only six months duration. They even produce new topographic forms of jumbled island and lake. Or they extend in cross channels called furos that anastomose between the courses of river and tributary in an atypical network fashion, until it is impossible to decide if the area is a river basin or a sea profusely segmented by straits.

A single flood season would completely destroy the work of a hydrographer.

The flora display this same imperfect grandeur. During the silent middays (the nights are fantastically noisy) one who might walk the forest does so with their gaze exhausted by the green-black of the foliage and, repeatedly encountering the arborescent ferns, which rival palm trees in height, and trees with straight, almost bare trunks, does so with the disquieting sense that they have returned to a much earlier time, as though they had invaded the recesses of one of those mute Carboniferous forests the existence of which is known to us through the retrospective gaze of the geologist.

That sensation of extreme antiquity is completed by the set of singular, and monstrous, fauna, where the amphibian dominates by dint of sheer sizeall of which adds yet further to the Paleozoic impression. And one who might wander along the rivers not infrequently encounters animals that exist, imperfectly, as abstract types or mere links upon the evolutionary ladder. The hideous bird called the cigana, for example, which perches on the flexible boughs of the oirana willows bearing beneath wings capable of only short-distance flight a reptilian claw.

Thus is nature portentous but at the same time incomplete. It is a stupendous construct lacking in internal coherence. We must bear in mind that, if the calculations of Wallace and of Hartt are correct, the Amazon region may well be the worlds newest land. It was born of the last geogenic upheaval, which raised the Andes and has barely finished its evolutionary process with the Quaternarian plains that are still forming and are preponderant within its unstable topography.

It contains everything and at the same time lacks everything, because it lacks that linking-together of phenomena developed within a rigorous process that produces the well-defined truths of art and of scienceand which bespeaks the grand unconscious logic of things.

Hence this peculiar singularity: in all America, Amazonia is the region most studied and simultaneously least well known. From Humboldt to Emilio Goeldifrom the dawn of the past century to our own daythe best minds have scrutinized it intently. Read them. You will see that none ever ventured beyond the great vertebrating valley. And even there each took refuge in the shelter of a specialization that absorbed him. Wallace, Mawe, W. Edwards, dOrbigny, Martius, Bates, Agassiz, to cite merely those who occur to me in first order, were in effect reduced to brilliant monograph writers.

Despite its abundance, the scientific literature on the Amazon reflects the physical geography of Amazonia: it is amazing, highly unusual and exceedingly disjointed. Any who dare study it carefully will, at the end of that attempt, get but a small way past the threshold to a marvelous world.

Professor Hartt had a phrase for the challenge that even robust spirits feel in the face of such an enormity. As he studied Amazonian geology, he found himself so thoroughly unmoored from the concise formulas of science and so carried away in dream that he suddenly felt obliged to lower the sails driving him toward fantasy: I am not a poet. I speak the prose of my science.