Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Penglase, Ben.

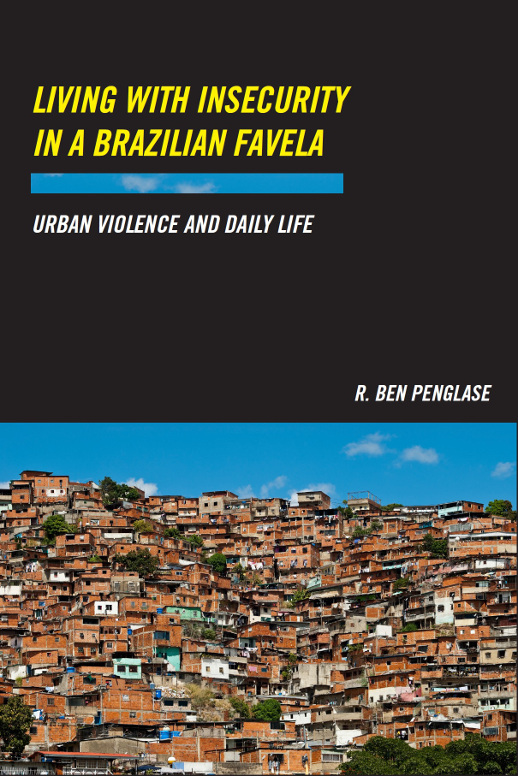

Living with insecurity in a Brazilian favela : urban violence and daily life / R. Ben Penglase.

page cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8135-6544-6 (hardcover : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-8135-6543-9 (pbk.)ISBN 978-0-8135-6545-3 (e-book)

Marginality, SocialBrazilRio de Janeiro. 2. ViolenceSocial aspectsBrazilRio de Janeiro. 3. Urban poorBrazilRio de Janeiro. 4. Caxambu (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil)Social conditions. 5. Rio de Janeiro (Brazil)Social conditions. 6. SlumsBrazilRio de Janeiro. 7. Squatter settlementsBrazilRio de Janeiro. 8. Drug trafficSocial aspectsBrazilRio de Janeiro. 9. Police brutalityBrazilRio de Janeiro. I. Title.

HN290.R5P46 2014

307.3'364098153dc23

2013042859

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2014 by R. Ben Penglase

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

Visit our website: http://rutgerspress.rutgers.edu

For Erika, the residents of Caxambu, and all the victims of violence in Rio de Janeiro

Many people have helped me with this project, over the course of many years. I am sure that I have forgotten many, but there are some that I cannot fail to single out. Erika Grinius convinced me that we really had to live in Caxambu, and read many, many drafts. Without her support and encouragement, this book never would have happened.

Aquele abrao also goes to the people whom I call Clara, Zeca, Seu Lzaro, Pedro, Dona Elsa, Dona Carmen, Anacleto, Tia Nan, my landlord Seu Nogueira, and all the residents of the place I call Caxambu. Without their help, patience, and encouragement this would not have been possible. They welcomed two gringos into their neighborhood and made sure that I rarely got lost and always felt like part of the family. In exchange they only asked me to tell it like it is. It was only long after my fieldwork was completed that I became aware of how often they were helping me without my even knowing it. My debt to them is enormous, not just for helping me (and putting up with my endless questions) and inviting me into their homes and into their celebrations, but for teaching me how to live.

Many other people have also been vital in introducing me to Brazil. Thanks must go to my parents, who exposed me to Brazil as a young boy, and who made me an anthropologist (as well as a Carioca de corao and a Flamenguista) before I was aware of it. Gilza, Marquinhos, and Elisabete also made me curious, at an early age, about lives that were so close to mine yet also so distant. Years later, Paul Chevigny, Juan E. Mndez, and James Cavallaro at Human Rights Watch reintroduced me to Brazil and reinstilled my curiosity and admiration for the Cariocas and other Brazilians who strive to make Brazil better, more humane, just, and no less vibrant.

Thanks also go to Gilberto Velho, Elizabeth Leeds, Alba Zaluar, Marcos Alvito, Lcia Valladares, and all the anthropologists and sociologists in Brazil who provided me with invaluable advice, inspiration, and encouragement. Nilza Waldeck, Rita Moriconi, Marisa Leal, and Mrcia and Fernando at the Fulbright office in Rio were also a great source of help. Viva-Rio was an immense help at various stages of my research.

A group of friends whom I met in Rio were, and continue to be, a source of inspiration and friendship. Luke Dowdney never let me forget what the whole point of such a project is, or should be. When I was living in Caxambu, Desmond Arias, Erica Windler, Peter Beattie, Luciana Lopez, Lgia Mefanoli, Amy Chazkel, James Woodard, and Jerry Dvila all provided shelter, great conversation, insight, and many saideiras.

As this book has come together, it has taken many different forms and has been read to and received responses from many people. At Harvard, Lucia Volk, Maria Clemencia Mencha Ramirez, Kathleen Gallagher, Haley Duschinski, and Bret Gustafson kept me on my feet, intellectually and emotionally. Kay Warren and David Guss also gave me critical feedback on this manuscript at an early stage. Thanks go to the many people who have organized and participated in panels and talks with me. They are too many to mention, but if you read this book and parts of it seem familiar, yet better, it is because of your help. Chapter 2, for instance, grew out of a talk given on a panel organized by Bernie Perley and Tracey Heatherington. Colleagues and friends at various institutions have also been immensely helpful, especially the Latin American writing group at Texas Christian University, which included Bonnie Frederick, Steve Sloan, Peter Szock, and Edna Rodrguez-Plate. At Loyola University Chicago, Kathleen Adams and Ruth Gomberg-Muoz have provided constant helpful advice and support.

I would also like to thank my editor and the staff at Rutgers University Press. Marlie Wasserman has been tremendously helpful and supportive. The anonymous reviewers of the manuscript also provided essential assistance. Thanks must also go to Margaret Case for her careful copyediting and attention to detail.

Portions of this book have appeared in articles that I have published elsewhere. Some of Chapter 2 was previously published, in a different form, in R. Ben Penglase, The Bastard Child of the Dictatorship: The Comando Vermelho and the Birth of Narco-Culture, originally published in The Luso-Brazilian Review 45 (1) 2008: 118145, by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System, reproduced courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Press. Parts of Chapter 4 were published in Ben Penglase, States of Insecurity: Everyday Emergencies, Public Secrets and Drug Trafficker Power in a Brazilian Favela, PoLAR: Political and Legal Anthropology Review, 32 (1) 2009: 407423. Portions of Chapter 5 appeared, in a substantially altered form, in Ben Penglase, Invading the Favela, in William Garriott, ed., Policing and Contemporary Governance: The Anthropology of Police in Practice, 2013, Palgrave Macmillan, reproduced with permission of Palgrave Macmillan (www.palgrave.com).

Two influences on this book are, sadly, no longer around to read the final product. David Maybury-Lewis saw the scholarly promise in me, and along with Ken George, Bill Fisher, Sally Falk-Moore, and Michael Herzfeld, helped make me into an anthropologist. Davids commitment to both anthropological inquiry and social justice continue to inspire many, including me. Begoa Aretxaga provided the initial theoretical inspiration for this project and continues to be a formative influence on my thinking. I like to think that shed be amused at how she haunts these pages.