For our Avani

PROLOGUE

DAY 4: JUNE 4, 2008 MILE 60

2:00 a.m. Storm near San Nicolas Island

(Latitude 3312, Longitude 11926)

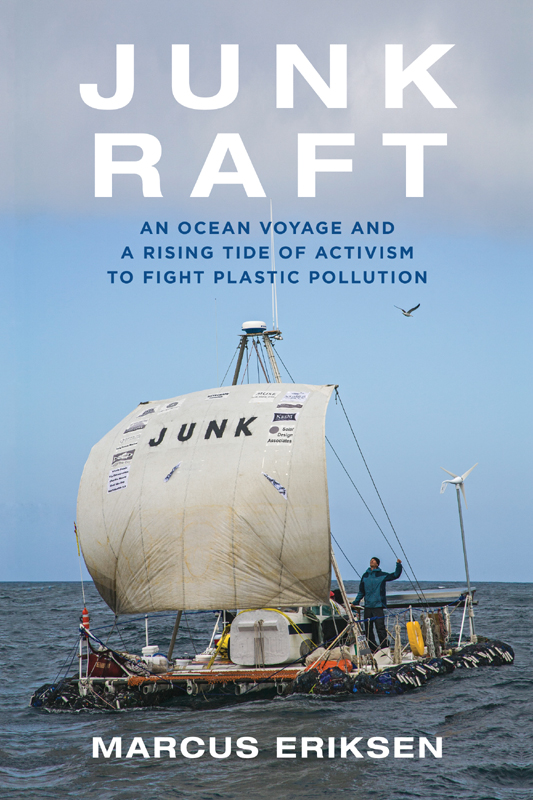

I n darkness, another wave slams against the underside of the airplane strapped to fifteen thousand plastic bottles. I pull the hatch closed to avoid more spray in my face. Water now sloshes under the plywood floorboard, between the bank of batteries and beneath our damp sleeping bags. The homemade rigging moans and whistles as fifty-knot gusts rip through. A wall of water engulfs the deck and blurs the windshield, and a cascade of echoing drips trickles through the holes I forgot to plug.

Somethings not right, I say.

I think the airplane just slid across the deck, Joel replies.

In these dark and timeless hours, were still huddled on a relatively horizontal plane, so at least were not on the verge of flipping over. We were near San Nicolas Island, sixty miles west of Los Angeles. I dont know if were still there. Like me, Joel is wide awake, trying to stay warm, nerves on edge. We jump with each new crack, moan, or sudden lurch of the raft. In the dim light of the coming day, I step outside into the sea.

One year earlier, Anna Cummins and I met in the kitchen doorway at Captain Charles Moores sixtieth birthday party at his home in Long Beach, California. Waves of blond hair unfurled around her neck. Little did I know that in eight months we would sail across the North Pacific Ocean to study plastic pollution aboard the Oceanographic Research Vessel (ORV) Alguita. Somewhere in the middle of that ocean I would climb up into the folded sails and ask Anna to marry me. But theres one thing, I said. I want to raft across the ocean.

We hatched a plan, asked the crew for volunteers. I sketched the final drawings of the raft. Joel Paschal, a fellow sailor on that same North Pacific research voyage, stepped forward and said, I like it. Together, he and I would sail Junk, a raft made from plastic bottles, with thirty old sailboat masts for a deck and a Cessna 310 airplane as a cabin. Anna would be mission control on land. No motor or support vessel buoyed our journeyjust us and the current, bound for Hawaii, imitating the path of trash into the swirling ocean gyre, those massive vortices of currents that suck trash into a stagnant center.

The Junk would turn out to be the first of many expeditions for Anna and me. In the years following the voyage of Junk, wed establish the 5 Gyres Institute, a research and advocacy organization, sailing around the world to all five subtropical gyres. In over fifty thousand nautical miles of sailing on twenty expeditions, wed invite some two hundred crew members, ranging from CEOs of plastic companies to educators, artists, activists, and policymakers, to help answer two questions: How much plastic waste is in the worlds oceans? and What can we do about it?

Our fight is to end the throwaway culture. Science in this synthetic century, riding the coattails of the Industrial Revolution, avoided the question, Where is away? In 2013, plastic producers broke the three-hundred-million-ton benchmark in terms of the amount of new plastic produced in a single year, and production is expected to exceed a billion tons annually by 2050. The industrys global solution to plastic is incineration, perpetuating the linear economy, from extraction to consumption, then destruction. To secure demand for new plastic, the industry must make last years plastic obsolete. Incineration is the essence of planned obsolescence, a concept central to twentieth-century capitalism, but a practice that cannot continue if we are to have a healthy and just existence.

Natural history is rich with unhappy endings. As short-lived, shortsighted, bipedal, big-brained primates preoccupied with war and sex, we risk consuming and overpopulating until we collapse. We fossil fools, driven to global conquest, havein the blink of a geological eyemade an enormous mess of things.

But I have tremendous hope. I am confident that we possess the collective intelligence and will to overcome the course that was set in the last century. Ive witnessed a growing movement to end throwaway living. Were fighting for a circular economy, in which little to nothing escapes unless it is benign to the environment. We need zero-waste and end-of-life design for everything we create; a world in which social and environmental justice becomes part of product and systems design. We want a world without wastebecause there is no away.

Are we capable of replacing the globalization of stuff with the globalization of new ideas to transform our culture of consumption? To rebut Kurt Vonneguts epitaph for our speciesNice tryI argue: Not done.

Another wave slams into the raft. I imagine it coming apart and sliding into the sea. I think mechanically through those seconds of impending catastrophe. The airplane, with only a few straps keeping it in place, will fall into the water and float for a moment as the tail rapidly turns downward like a bobbing cork. Four hundred pounds of batteries loosely arranged on the floor will come crashing onto Joel and me as the fuselage fills with seawater. It will be a quick drowning, and well likely never be found.

I remove the satellite phone from the dry bag and call Anna.

Hey.... Were sinking.

CHAPTER 1

SYNTHETIC SEAS

Economists have a term for these costs.... They are negative externalities: negative because they arent beneficial and external because they fall outside the market system. Those who find this hard to accept attack the messenger, which is science.

Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway Merchants of Doubt, 2010

B eginning in this century, news accounts painted a dire picture that captivated the world: images of drifting plastic masses, of marine mammals, sea turtles, and birds choking on plastic bags. Young entrepreneurs clamored to clean those mythical islands of trash, while industrialists rose to defend plastic. From this melee, a new field of science emerged to sort fact from fiction. A cast of characterssailors turned scientists and scientists turned activists, and activists who turned to politicsset the stage for a dramatic comedy of fossil fools, as behemoth petrochemical corporations rose like phoenixes to counter a public relations nightmare.

I was one of those fools. I did not arrive at a career in science by the traditional rigorous academic path, but in haphazard leaps from one experience to another, wielding my ignorance like a quixotic sword. Just as theres no straightforward path to scientific knowledge, theres no one method of becoming a scientist. My path began with a naturalists dream and took me through a war and a river home. Along the way I bore witness to an ecological atrocity and to the complexity of self-preservation through conservation and social justice.

In 2000, I visited Midway Atoll, the last island along the Hawaiian archipelago in whats now the Papahnaumokukea Marine National Monument, where I met biologist Heidi Auman and her collection of odd artifacts, items that had been swallowed by Laysan albatross, including light bulbs, armies of little green men, glow sticks, golf balls, and a syringe (found with its needle protruding from a living birds chest). Aumans a young scientist, with long blond hair that contrasts with a tan from hours of fieldwork studying these birds. As we wandered the island we picked up toothbrushes, an asthma inhaler, half a spoon, an electrical-wire nut, an action-figure leg, and cigarette lighters from the bleached rib cages of dead albatross. One lighter bore the clearly legible phone number for some bar in Tokyo. I could have called them to say, Hey, you dropped something.