Chapter One

A SURPRISE AT SEA

Captain Charles Moore felt the wind across the north Pacific Ocean die to a whisper. A few weeks earlier, it had filled the sails of the Alguita, pushing the white 50-foot-long (15-meter-long) sailboat west from California to Hawaii in the 1997 TransPacific Yacht Race. He carried a trophy for third place and was enjoying brisk winds pushing him and his crew back home to California until now. Moore had scanned weather reports and turned the Alguitas bow southeast. It had entered an expanse of ocean that was as still as a painting.

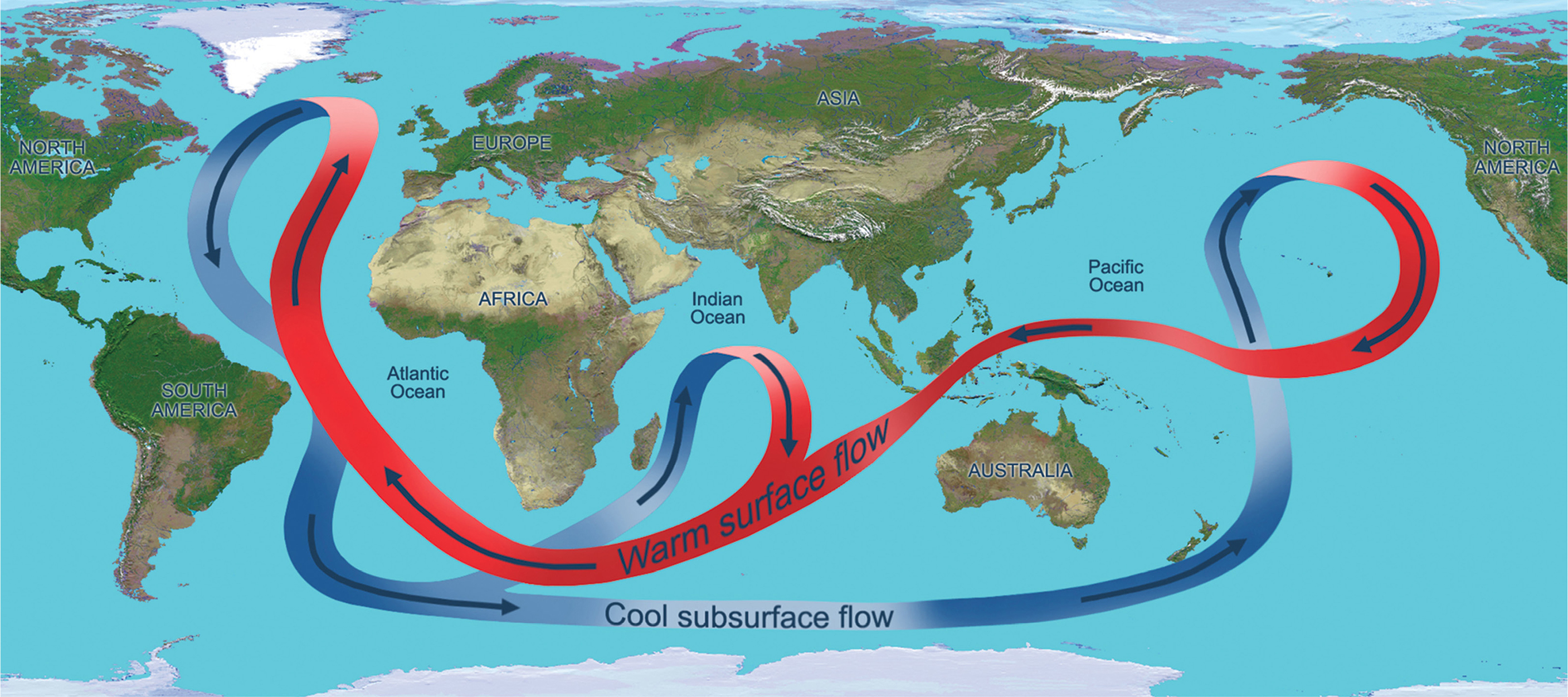

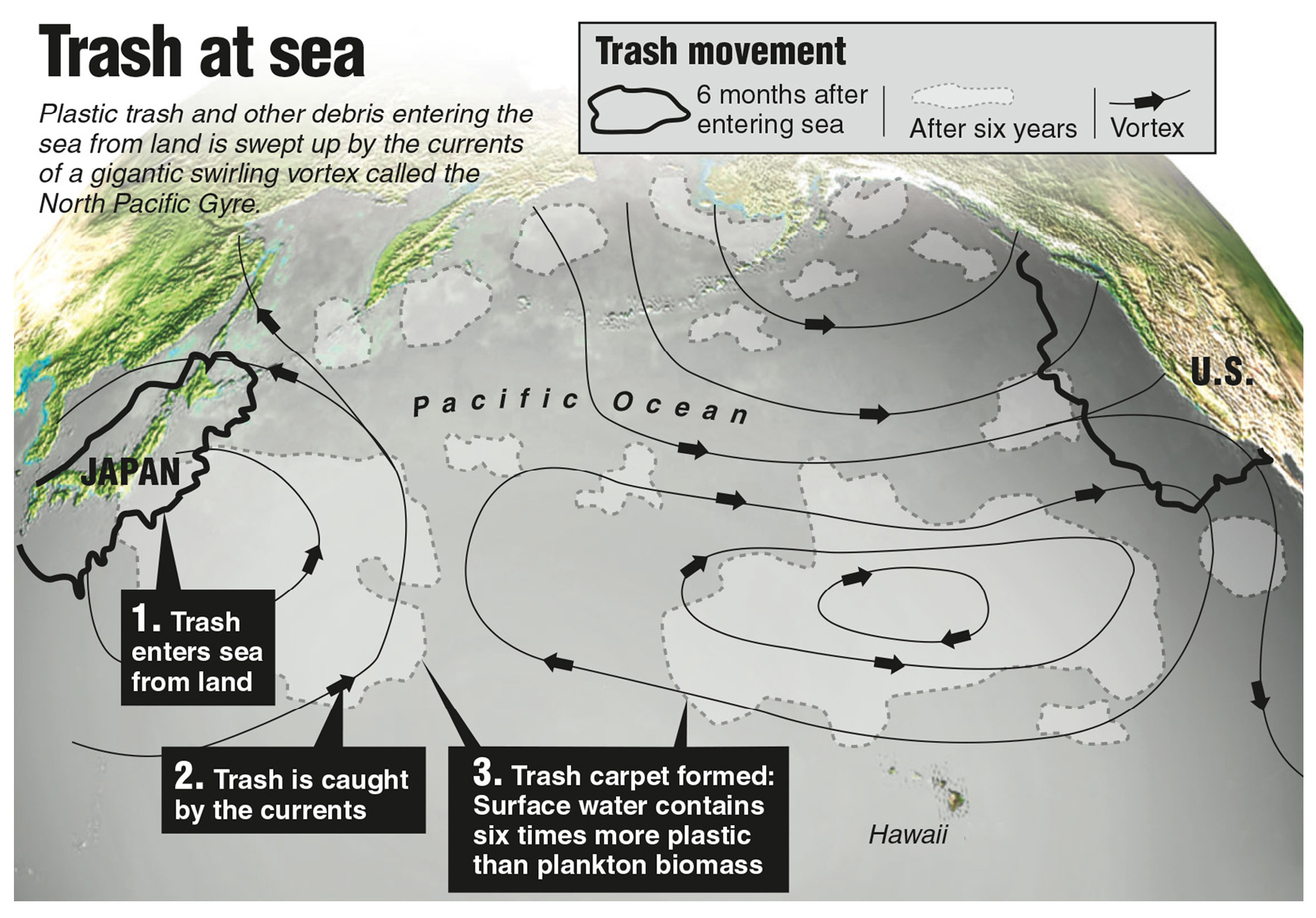

Sailors usually try to avoid the north Pacific Ocean. The weather there is not too stormy or unpredictable, but too calm. Legends tell of desperate sailors waiting so long for wind that they had to conserve drinking water by drowning their cargo of livestock. Sailors and scientists now understand that this quiet expanse of ocean is the center of a gyre (pronounced JI-er), a whirlpool that is thousands of miles wide. Powerful currents flow around the outer edges, like rivers through the ocean. Driven by the wind and Earths rotation, the currents sweep west across the Pacific Ocean and up the coast of Asia. Then they move east across the ocean, down the west coast of North America, and west to begin the cycle again.

Captain Charles Moore and his research sailboat, the Alguita

The water encircled by the currents turns clockwise sluggishly. Moores modern sailboat was equipped with diesel engines, a system to make seawater drinkable, and a radio to call for help. Even so, a detour across these calm waters would haunt him. It would convince him that the ocean held a danger so great that it threatened the survival not only of his crew, but of organisms all over the globe.

On August 8, while standing on deck, Moore saw something unexpected. Here and there, odd bits and flakes speckle the oceans surface,

Moore returned to Alamitos Bay, California, where he had spent his youth swimming, surfing, and sailing in the Pacific Ocean. By the 1980s, he wrote, pollution of many kinds made residents think twice about eating a He wanted to know why it was there.

A National Aeronautics and Space Administration map of ocean currents depicts warm surface currents in red and deep ocean currents in blue.

Oceanographer For more than a decade, ducks traveled and landed on shores in South America, Europe, Australia, and even the Arctic. Ebbesmeyer realized that the 11 gyres in the worlds oceans, along with ocean currents, work together like a giant conveyor belt, circulating seawater and everything floating in it.

Ebbesmeyer convinced Ebbesmeyer has estimated that a 1-liter plastic bottle crumbles into enough microplastic pieces to put one on every square mile of the worlds beaches.

A PORTRAIT OF PLASTIC

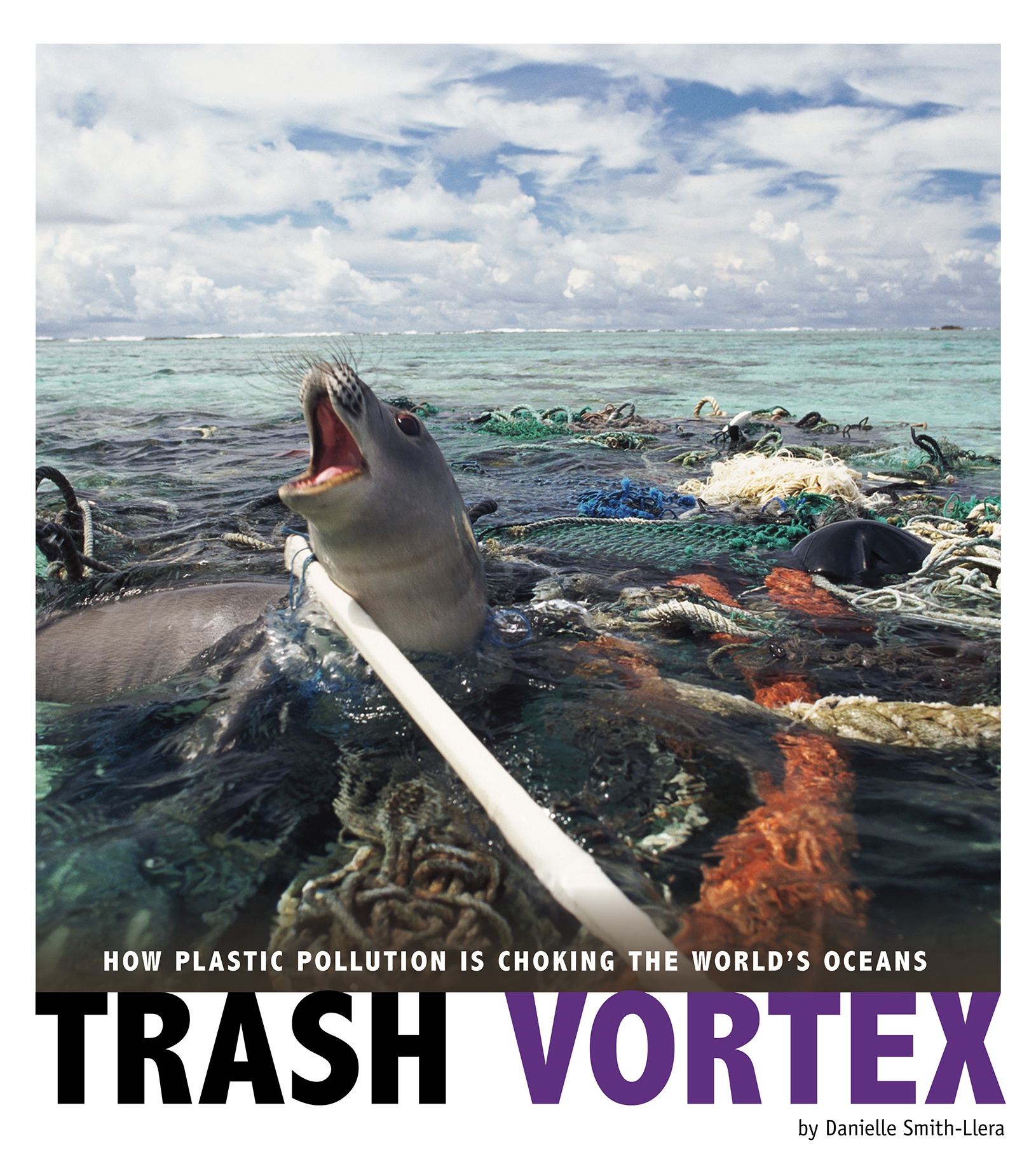

Plastic trash in the

But locating the nearly invisible microplastics in the ocean takes computer modeling software and a lot of patience. Researchers sail into gyres with nets, called trawls, that drag behind their boats. The nets skim the surface, collecting microplastics. Researchers count the microplastics caught in the tiny mesh with the help of tweezers and sometimes with a microscope. Computer technicians combine new data and thousands of measurements of microplastics collected since the 1970s with information about currents to create maps of where microplastics could be floating.

But the maps are only guesses. Vast parts of the ocean have not been sampled, especially in the Southern Hemisphere. Whats more, floating plastic accounts for only 1 percent of the plastic that enters oceans, so much of plastics ocean journey remains a mystery. We must learn more about the pathway and ultimate fate of the missing plastic,Cozar Cabaas.

Currents and gyres circulate water and plastics around the worlds oceans.

that Ebbesmeyer believed was there.

Some plastic trash was easy to find. Moore observed that similar objects find each other in the middle of millions of square miles of seemingly empty ocean, and the ocean stitches them together, making a grotesque whole. We dive around this strange mass, avoiding the undulating tendrils of rope and net and deciding it could make a convincing sci-fi monster.plastic fragments.

The Alguita docked in Long Beach, California, for a summit with students and teachers about plastic pollution.

Using fine-meshed Moore wrote.

Moore hauled home barnacle- and algae-covered plastic garbage from the three-week voyage. He displayed it on the plankton.

I wasnt the first to be disturbed about plastic trash in the ocean, and I wasnt the first to study it, said Moore. But maybe I was the first to freak out about it.gyre the Worlds Largest Dump. The name Great Pacific Garbage Patch caught on.

The microplastics in Moores samples collected in the Pacific Ocean far outweighed the plankton.

The public did not fully understand what Moore had found. When he described the plastic-stricken area as being twice the size of Texas, people imagined an island of plastic garbage that you could almost walk on,

Chapter Two

SHAPING A MODERN LIFE

Charles Moore discovered an unusual rock on Hawaiis Kamilo Beach in 2006. When Canadian geologist Patricia Corcoran heard about it, she flew out to see it. The lump contained shells, coral, wood, and volcanic rock and sand, all fused together by great heat and plastic. She named it plastiglomerate and determined that it had been created by bonfires built by campers on the trash-strewn beach. Corcoran inspected the beachs larger plastic trash and found it had traveled from Russia and Asia, riding a gyres currents. Colorful microplastics mixed with grains of beach sand how did they get to this Hawaiian beach so far from the open sea?

Oceanographer Henderson Island in the south Pacific Ocean, for example, is remote and uninhabited, yet littered with 38 million pieces of plastic.

Like a chunk of plastiglomerate, todays beach sands hold history. Every little piece of plastic manufactured in the past 50 years that made it into the ocean is still out there somewhere because there is no effective mechanism to break it down,Anthony Andrady.

Beaches littered with plastic and other types of trash are found around the world.

Seaglass and bits of ceramic and rusted metal also mix with beach sand to tell an older story. People have always been searching for the best materials to shape into the necessities and luxuries of everyday living. They learned to mold clay, hammer metal, and melt sand into glass. They shaved thin sheets of animal horns to make translucent panes for lanterns. These materials are plastic in the sense that they can be easily shaped. The English word plastic comes from the Greek word