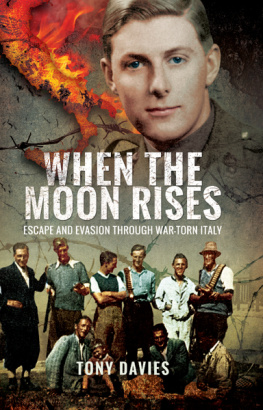

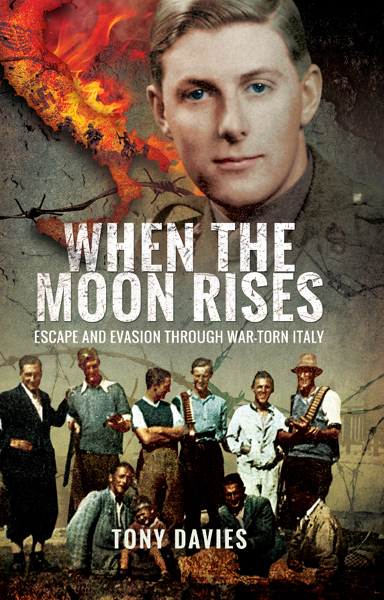

WHEN THE MOON RISES

Escape and Evasion Through War-Torn Italy

First published in 1973 by Leo Cooper Ltd., London.

This edition published in 2016 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright Tony Davies

The right of Tony Davies to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-457-2

PDF ISBN: 978-1-84832-460-2

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84832-459-6

PRC ISBN: 978-1-84832-458-9

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in 10.5/13 point Palatino

For more information on our books, please email: , write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

Contents

PART I

Escape and Recapture |

PART II

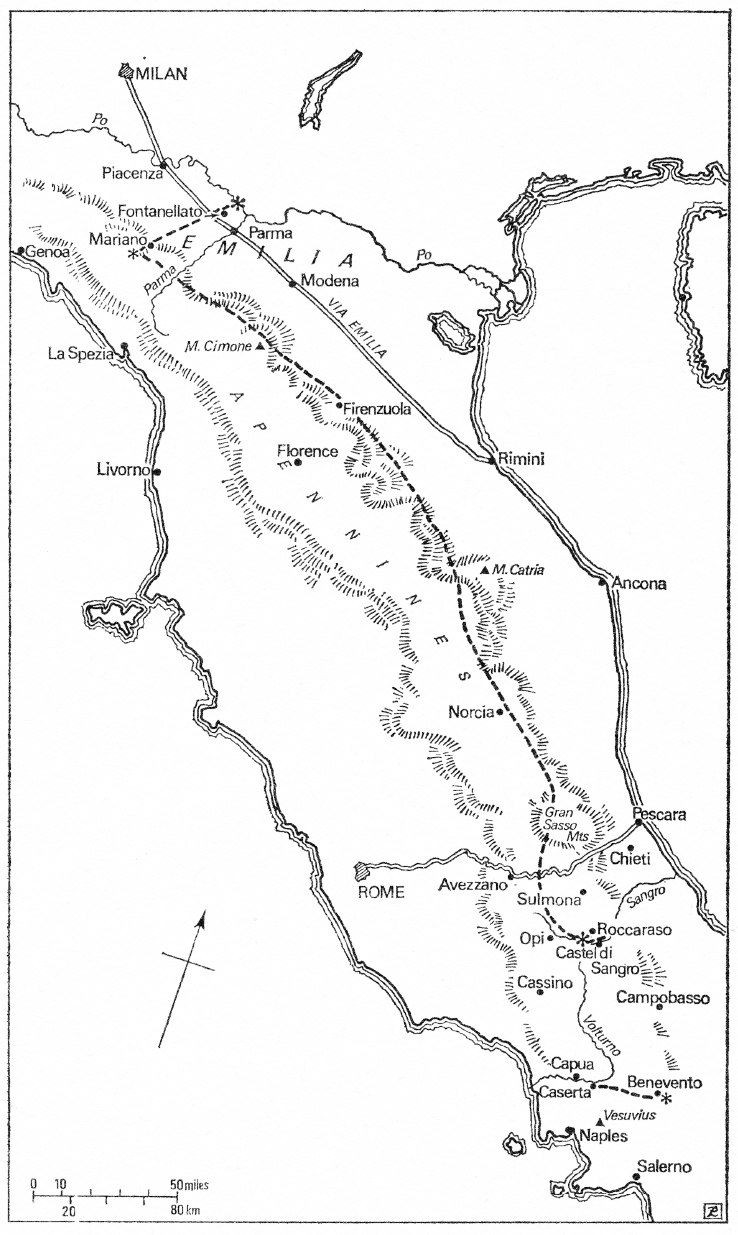

The Long Walk South |

Foreword

I first met Tony Davies when, together with his companion-in-arms, Michael Gilbert, he emerged from the punishment cells at Campo P.G.21 after an extremely courageous attempt to escape from Italy in the spring of 1943, a feat which no allied prisoner of war succeeded in performing, so far as anyone knows, until after the Italian Armistice in September of the same year.

They had jumped from the window of a moving train at night and were very lucky to be alive, for train-jumping is one of the most hazardous methods of escaping: the take-off through the window has to be nicely judged, especially if there are telegraph poles along the line. These impediments and the presence of armed sentries in the corridor or the compartment itself, who are invariably sentenced to long terms of imprisonment if they fail to shoot straight, make the prospect for the jumper poor indeed and if two jump from the same compartment the prospect for the second is even worse.

Tony was tall and debonair as befitted an officer in a crack regiment of artillery, and thirty years later as a hardworking GP with a country practice he still is; but what really endeared him to me was his slightly loony appearance caused by a snaggle tooth, his infectious laugh which reminded me of Jack Hulbert giving an impromptu rendering of The Flies Crawled up the Window in the Casino at Monte Carlo before the war, and his incurable optimism, all of which survive to this day except the twisted front tooth which unfortunately was removed by a dental surgeon before I could clamp a preservation order on it.

Soon after their release from the cells we moved to a new camp further north at Fontanellato, a place so luxurious in comparison with any other camp we had so far inhabited that the wildest rumours circulated, the most acceptable being that we had been brought to it so that we might be fattened up and made sufficiently presentable to be exchanged for a similar number of Italian prisoners of war.

This, of course, was utter nonsense and so little believed by anyone in their right minds that escape attempts flourished and I found myself involved with Michael, whose brainchild it was, Tony and a number of others in the digging of a tunnel. It started on the first floor of the mock palazzo we inhabited and descended vertically through the solid brickwork of one of the piers which sprang from the floor of a crypt-like cellar in which we took our meals and which supported the entire edifice so that when digging ones way to freedom as some books would have it (not this one I am glad to say), one had the sensation while working at the face of being underground with ones feet in the air whereas one was actually poised in mid-air between the floor and the ceiling in the cellar. This dreadful, insensate labour was only brought to an end by the Armistice. I was in the prison hospital with Michael when the news came through. He had a huge carbuncle, I had a broken ankle and it was this that prevented me from accompanying Michael, Toby Graham and Tony on the great walk chronicled here. Reading it now, I think I had a lucky escape.

The next time I met Tony was in the wilds of Czechoslovakia in 1944. Our paths had diverged for a time but one thing that we had both learned was the courage and humanity of ordinary Italian people when everything seemed at its blackest and this is what When the Moon Rises is really all about.

Eric Newby,

Author of

Love and

War in the

Apennines.

March, 1973.

Glossary

AA | Anti-aircraft |

NCO | Non-Commissioned Officer |

OCTU | Officer Cadet Training Unit |

ORs | Other Ranks |

P.G. | Prigione di Guerra |

PoW | Prisoner of War |

RAF | Royal Air Force |

RN | Royal Navy |

RTO | Railway Traffic Officer |

SBO | Senior British Officer |

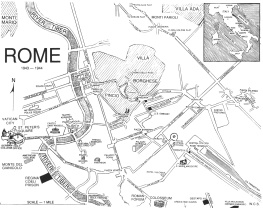

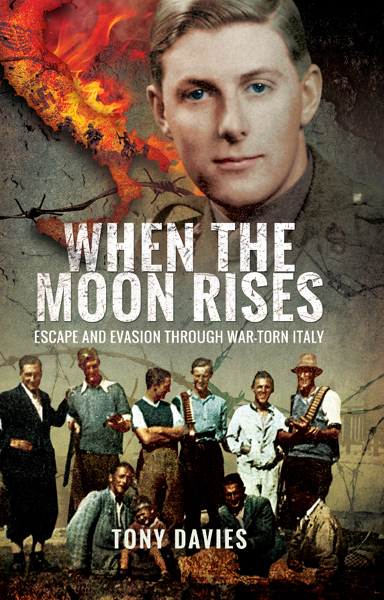

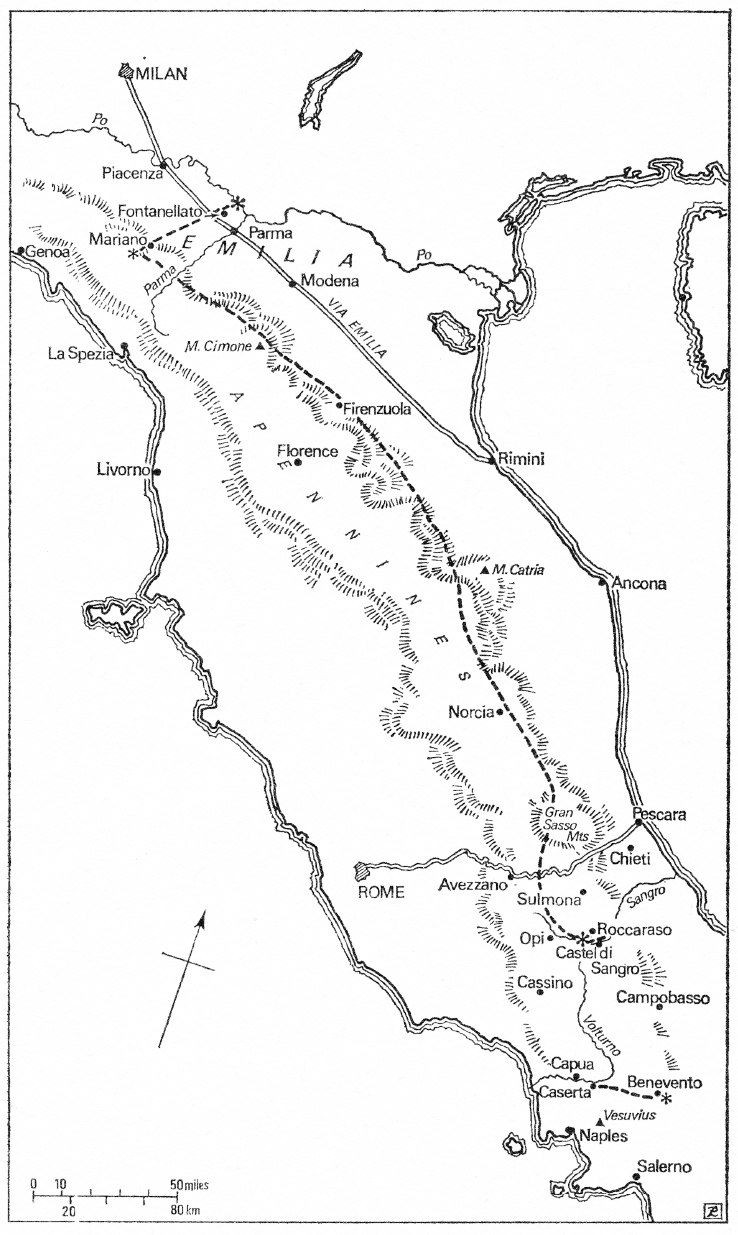

This photograph was taken near the summit of Monte Cimone (7,100 feet) in October 1943, by an Italian photographer, a member of the band of partisans. The author is standing second from the left, Toby Graham fourth from the left and Michael Gilbert on the right. The others in the picture, with the exception of the child, are deserters from the Alpini Regiment who later formed the nucleus of a partisan banda. The cylindrical object on the right is a gas cylinder mounted on the back of a Volkswagen.

Prologue

Capture in Tunisia

B ehind and above me in the light of the full moon rose the shoulder of Two-Tree Hill, shorn of its characteristic topknot since being taken by the London Irish, with appalling losses, a couple of days before. Below and ahead, somewhere, lay the Germans, inspired with renewed purpose since the arrival in Tunisia of General von Arnim. It was 02.00 hours on the morning of 16 January, 1943.

For the moment, as my signaller and I peered into the moons deep shadows, everything was peaceful. It was one of those brief lulls which, in retrospect, are lent a quite disproportionate significance by what happened afterwards. At the time, crouched in the slit trench on the forward side of the hill, and with memories of the hard fighting of the previous few days still fresh in mind, one was conscious of an equally deceptive, though tightly-stretched, tranquillity. One hoped, but did not quite believe, that the enemy had pulled back, that we might be left in peace to recover and reform after the mauling we had received.

This was the period immediately after the great three weeks rain, when the Allies, with a firm foothold on the Algerian coast, had tried and failed to take Tunis at a single stroke. The rain, grounding aircraft and halting tanks, had seen to that. Now, faced with a regrouped and determined German army, we seemed fated to fight out the winter in the Tunisian hills round Medjez-el-Bab. The Honourable Artillery Company Regiment, of which I was a junior member, had only been in North Africa for two months. We had left Britain in November and landed in Algiers after the first wave of the invasion was successfully ashore. From there we had been shipped by destroyer, under constant air attack, to Bone, where we had picked up our vehicles and joined up with the French Foreign Legion. There had been one or two skirmishes and a notable fiasco on Christmas Day before the line had been stabilized in the region of Medjez-el-Bab. A large-scale German tank attack had been successfully repulsed; and then, for three weeks of continuous downpour, we stuck. The RAF, with no all-weather airfields within reach, could not help us, and the Stukas plastered us regularly and without serious interference. It was a galling time.

Next page