First published in Great Britain by Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, 2012

A CBS COMPANY

In association with Imperial War Museums

Text copyright The Trevor Greenwood Archive and Imperial War Museums 2012

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission.

All rights reserved.

The right of Trevor Greenwood and S. V. Partington to be identified as the author and editor of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1998.

Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

1st Floor

222 Grays Inn Road

London WC1X 8HB

www.simonandschuster.co.uk

Simon & Schuster Australia, Sydney

Simon & Schuster India, New Delhi

Every reasonable effort has been made to contact copyright holders of material reproduced in this book. If any have been inadvertently overlooked, the publishers would be glad to hear from them and make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

Maps Peter Beale

Cover image is a composite of more than one photograph.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-47111-068-9

eISBN: 978-1-47111-069-6

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Editors Note

As is often the case with diaries, Trevor Greenwoods original notebooks contain a great many abbreviations and contractions in the writing. These have been spelt out in full wherever necessary, either for clarification for example, where Trevor wrote going to S. for going to the Solent and WKM for Wickham or for ease of reading.

Many of the abbreviations and acronyms were common army usage and, indeed, still are so and these have been left as Trevor wrote them. Readers from a non-military background will find the List of Abbreviations that precedes the diary useful in deciphering their meaning.

The weapons, vehicles and aircraft mentioned in the diary are identified and, where helpful, explained, in the Glossary of Military Terms and Equipment. The brief note on The Organisation of 9 RTR explains the higher formations to which the battalion belonged, as well as the role of the echelons into which it was divided, since these can otherwise be confusing to the general reader.

The diary itself is followed by a superbly informative essay on 9 RTR in Normandy by John Delaney of the Imperial War Museum, which sets the events recorded by Trevor in their historical context, expanding on the battles in which he took part and explaining the role of the tank as infantry support.

Trevor used underlining for emphasis and quotation marks for names of ships, films, foreign words and so on, and these have been replaced throughout by italics. I have, however, kept the quote marks he used when writing about the echelons into which 9 RTR was divided, A, B and F. This is to distinguish them from the squadrons A, B, and C, since the diary sometimes refers to both echelons and squadrons by letter alone.

The occasional spelling has been modernised: loudspeaker, for instance, has long since lost the hyphen it possessed in the 1940s: to retain it would read rather quaintly to us today.

The diary refers in places to Trevors family and friends, and in order to avoid the need to footnote them, these purely personal connections are identified below.

Dorothy, Kath and Marjorie were Trevors sisters. Tod, or Toddy, was his brother, married to Olive. Bob and Fred were married to Kath and Marjorie respectively. Garsden was a work colleague in England, as was Mr Morgan. Trevors son, Barry, (aka Poppet) was eleven weeks old when the diary opens, and Trevor had seen him briefly just once before leaving England. Haydn Dewey was Trevors cousin; Aunt G or Aunt Gertie was Haydns mother, and Trevors fathers sister. Johnny was the younger brother of Jess, Trevors wife. Phyl was Phyllis Lambert, Jesss cousin, who later married Lance Corporal Ernest Bland. Wilf Colclough was a close friend of Trevors, who wrote to him often, and with whom he shared an active interest in politics. Stan Smith was a lifelong friend who shared Trevors deep love of music: several of his letters to Trevor survive.

Military personnel who were also known to Trevor and Jess outside of Trevors army life include Noel Wright, Dave Lubick and Jimmy Aldcroft. The Wrights were near neighbours, and Jess was in close touch with Mrs Wright and with Mrs Aldcroft throughout the war. Bob Plowman also appears to have been both a friend and a one-time army colleague, although his precise connection is less certain.

Space precludes the individual identification of all the army colleagues who are mentioned in the diary. Readers who wish to know more about 9 RTR and the men who served with it can find a wealth of information on the official website of the Royal Tank Regiment Association at www.royaltankregiment.com, which contains within it a site dedicated to 9 RTR under the link to Disbanded Regiments. Amongst the admirable resources to be found here are the complete 9 RTR War Diary, a privately published History of the 34th Armoured Brigade and the full text of Tank Tracks, a history of 9 RTR in action, written by Peter Beale, a veteran of B Squadron.

The assistance provided by Peter Beale has been especially valuable in helping to bring the diary to publication; both in explaining and identifying many of the more puzzling or obscure references, and in allowing us to use his wonderfully clear and comprehensive maps.

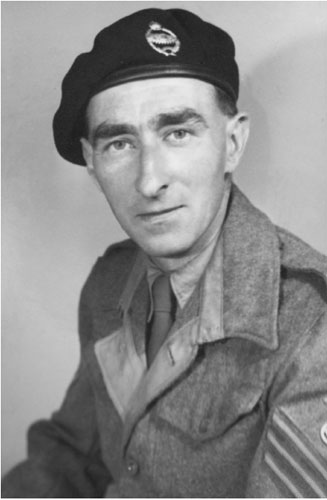

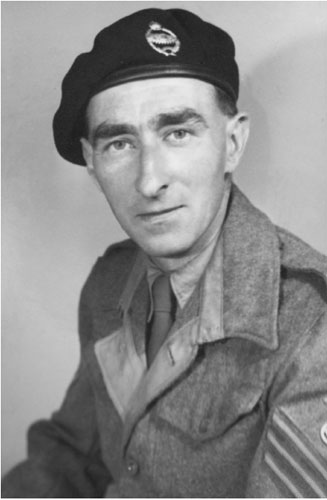

1. Sergeant Trevor Greenwood.

Photograph The Trevor Greenwood Archive.

Foreword

Our parents, Richard Trevor Greenwood (190882, known as Trevor) and Jessie Whitaker (191099, known as Jess) lived in Reddish, near Manchester, and moved to a house in Hazel Grove, near Stockport, after their marriage. Trevor worked for the Ediswan Electrical Company as an electrical sales engineer and Jess was a clerk at the Public Trustee Office until their son Barry was born in March 1944.

Trevor was amongst the first batch of conscript recruits to arrive in Gateshead on 27 November 1940, when the 9th Battalion Royal Tank Regiment was reborn. From then until his demobilisation in December 1945 he kept up an almost daily correspondence with our mother which records in great detail his progress through the war, from the long period of training in Britain, through to active service in Europe and post-war policing duties in Germany. He also kept a diary which provides a detailed, uncensored eye-witness account of events from D-Day (6 June 1944), to 17 April 1945.

The letters reveal that Trevor was selected for a fast-track course in D&M (Driving and Maintenance). Thus began his army career in Churchill tanks, and his training took him all over the country. From 13 April 1944 until the end of the war, the whereabouts of 9 RTR could not be revealed. In fact, the regiments final preparations took place in Lee-on-Solent near Gosport, where they awaited embarkation for Normandy. In Trevors case, active service in Normandy began on D-Day +16.

The diary consists of seven notebooks, some left with blank pages. Trevor knew that he was contravening regulations by keeping a diary, and took any opportunity to send these volumes back with trusted colleagues returning to England on leave or through injury. The sixth volume ends on 14 February 1945, with many unused pages. This was the day Trevor went on leave, his only home visit during the period covered by the diary. Why he risked keeping a diary is a mystery, but he was certainly conscious of the momentous importance of the events he was witnessing, and wanted to deliver an accurate account for posterity. His incessant writing, particularly in the more intimate context of his letters to Jess, also fulfilled a cathartic need to keep closely in touch with the preferred reality of his home life. In recent years his former friend and squadron colleague Dicky Hall told us of the many hours spent by Trevor sitting in his tank turret with pen and notepaper. It is interesting to note that long descriptions in the diary, particularly of battles, are sometimes reproduced verbatim in a letter a few weeks later. This delay was to comply with the strict rules of censorship; for example, the battle for Le Havre: diary entry 12.9.44, letter 9.10.44. Presumably Trevor had in mind that this approach would fulfil two purposes: it provided interesting material for long letters to Jess, and preserved accurate accounts of significant events in case his diary did not survive.

Next page