Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my mother, Wang Jinxiang; and my wife, Yuan Weijing

In the world as we know it, are there things that are difficult, as well as things that are easy? Through action, those things that seem difficult become easy; with inaction, things that are easy become difficult.

Peng Duanshu (16991799), from On Studying

Bring forth all that is good in the world, and expunge all that is bad.

Mencius (372289 BCE), from Universal Love III

One who is shut indoors may come to know the world; one who cannot look out the window may understand the Way of Heaven.

Laozi (fifth century BCE), from the Dao De Jing

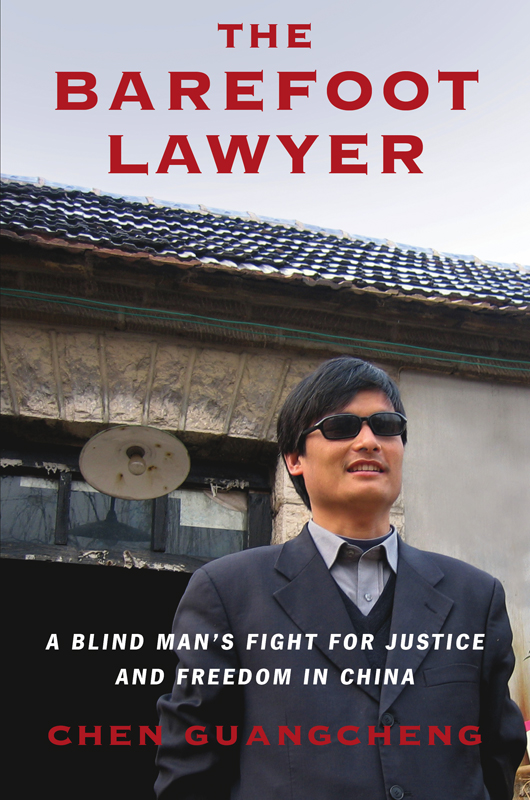

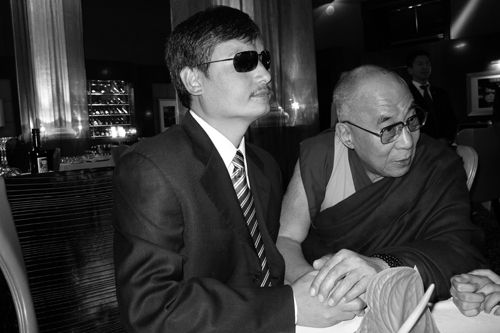

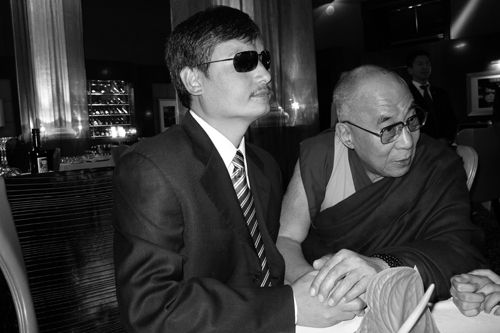

I welcome this publication of Chen Guangchengs memoirs of his life so far. Its a story that should be told because it shows clearly that with determination, confidence in yourself, and a concern for others you can overcome adversity. Chen Guangcheng overcame the significant setback of blindness and social prejudice and gained an education. He put that education to use by helping and advising the poor people in rural areas who have no one else to turn to.

In the clarity of his motivation Chen Guangcheng reminds me of the first generation of communist leaders I met in China sixty years ago, who at the time impressed me with their genuine concern for the welfare of the mass of ordinary people. When his barefoot activism attracted the attention of vested interests he was tried and imprisoned on the contrived charge of disturbing the peace. When, on his release, he discovered that his own and his familys normal life activities were restricted by the authorities, he decided to escape. He succeeded, in as much as he and his family have been able to start a new life in the freedom of the United States; however, he continues to champion for the rights of his fellow brothers and sisters, especially the rights of the rural poor.

During my meetings with Chen Guangcheng I was impressed by his drive and warmheartedness. Helping people help themselves as he did is no threat to the peace and order of society, but can instead contribute to its harmony. I look forward to a time when China is able to embrace and accommodate inspiring and well-motivated people like Chen Guangcheng and Liu Xiaobo; people like them have a positive role to play.

October 18, 2014

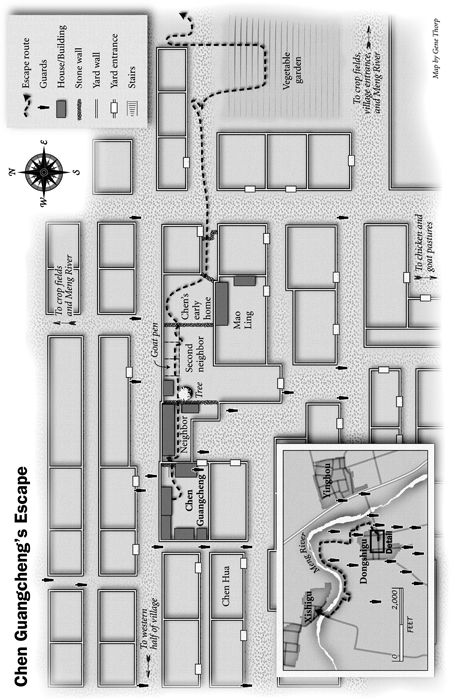

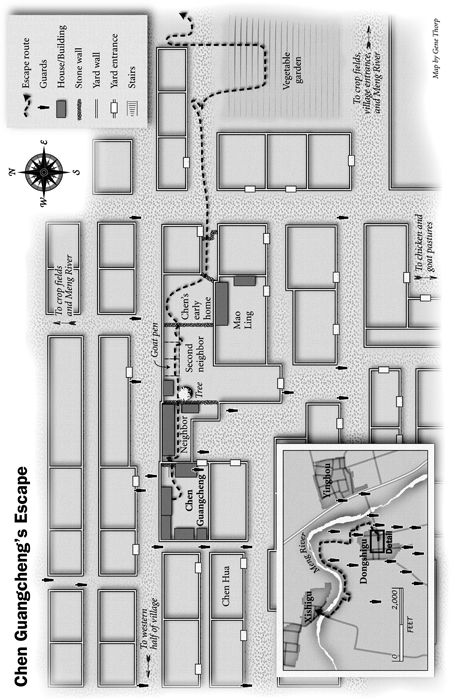

We watched them as they watched us. We studied their every move and every habit. We had been planning my escape for over a year, going over the details again and again in muted whispers. We assumed that the house was bugged, that our captors could hear every word we spoke.

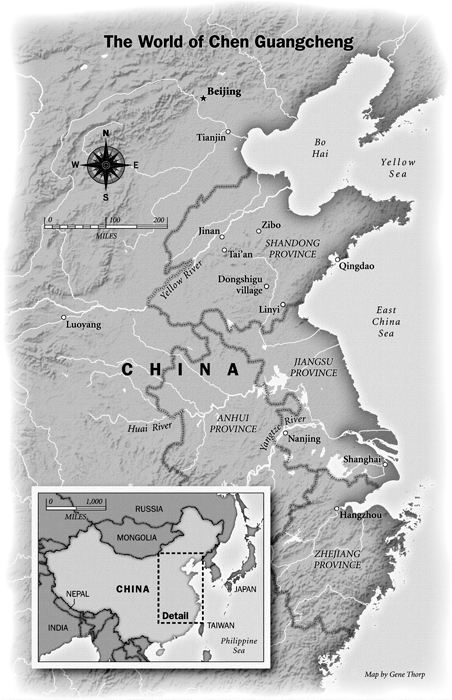

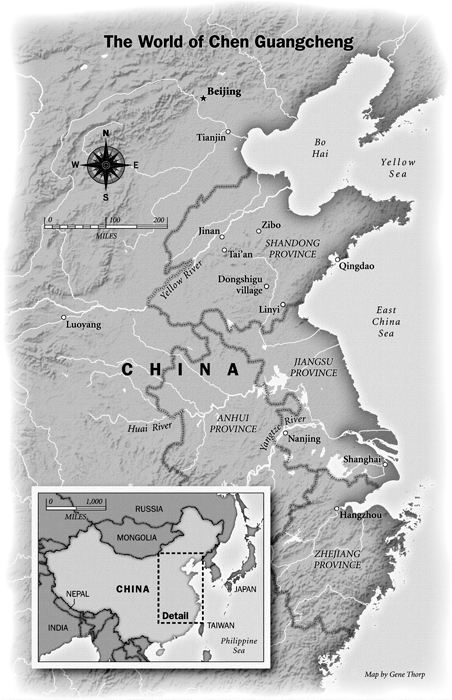

If I could just get beyond the villagebeyond what had once been a home and was now a private hell, beyond the seventy or more guards laying siege and blocking every possible exit. Home will be no better than prison, a warden had told me shortly before I was released from jail after being confined for over four years. And he was right: once back in Dongshigu, I had been kept under brutal house arrest, an epicenter within the vast prison that all of China had become.

By now I had already attempted to escape my home numerous times. My wife, Weijing, and I debated and discussed the hazards and benefits of each plan endlessly, and I went through each possible route in my mind, over and over. I was desperate to escape: my life, not just my spirit, depended on it. Gravely ill since prison, I was not allowed to see or even speak to a doctor. My isolation in my own house was almost total: no going out, no visitors, no news, no contact with the outside world. I had severe diarrhea, often with bleeding, and I constantly felt exhausted. Recently Id been spending about two weeks out of every month in bed, too sick to move. If I finally lost my battle to live, the authorities would say that I had died of such and such illness, at home in my own bed, and who would know the difference? Resolve was all I had.

On April 20, 2012, Weijing and I spent the morning resting in the main room of our house, which was one of four small buildings around a dirt courtyard that made up our family compound. A few days earlier wed realized that the neighbors dog was gone. Id often said that one dog was more dangerous than a hundred guards, and now, with this one away, we focused our attention on the escape route that would take me past that neighbors house, to the east.

That morning, as usual, I went through the route in my mind, dwelling on every detailexactly where to turn, the distances between things, the walls, all the minutiae that Weijing had gathered during her daily routines over a period of months. Only she and I knew of our plan, though we agreed that when attempting to get past the guards, I should try to find help in the village, from either a close childhood friend or another good friend who was a carpenter. Both lived along my path of escape, but we had no way of communicating with anyone outside our house. It was too dangerous to tell even my mother about the plan; she strongly objected to the notion that I should try to escape.

Weijing and I had often talked about how I would get word to her once I was safe. We couldnt use written or spoken communication, so the only possibility was to send a sign, a signal. Eventually we decided that if I got out alive, I would have someone deliver six apples to Weijing; in Chinese, six can signify success, and the word for apple is the same sound as that for safe. I imagined having someone bring her six big red apples once I got away from our village, and if there were none to be had, I figured I would find a way to get her six of something else so she would know that I was free.

All that morning, Weijing observed the guards from inside the house, watching for an opportunity. Earlier, up on the roof of our flat kitchen building, where we dried corn and aired out our clothes, shed noticed that the car belonging to the head of the group of guards on duty was gone. There were usually six guards stationed in our yard, perched on tiny stools just outside the door to our house. The crew on duty today sat near our main gate, and only two of them had a direct line of sight to our door. A little before eleven a.m., the moment suddenly came: the guard closest to us slowly stood up, a tea mug in his hand. He was off to fill it with boiled water from one of the thermoses the guards kept outside our yard, and he didnt seem to be in a hurry. On his way, for just a few seconds, he would block his partners view of me. I would have to hurry out the door and dart across the courtyard to the eastern wall, a distance of about fifteen feet. After a moment, the guard would have his sight line back.