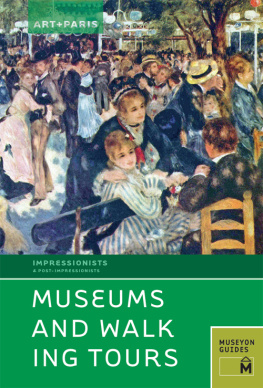

Museyon Inc.

Published in the United States by:

Museyon, Inc.

20 E. 46th St., Ste. 1400

New York, NY 10017

Museyon is a registered trademark.

Visit us online at www.museyon.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be copied or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, except brief extracts for the purpose of review, and no part of this publication may be sold or hired without the express permission of the publisher.

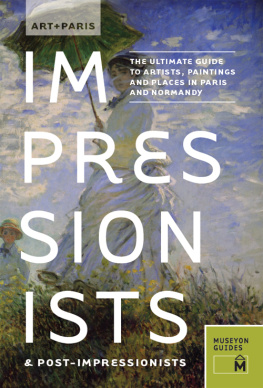

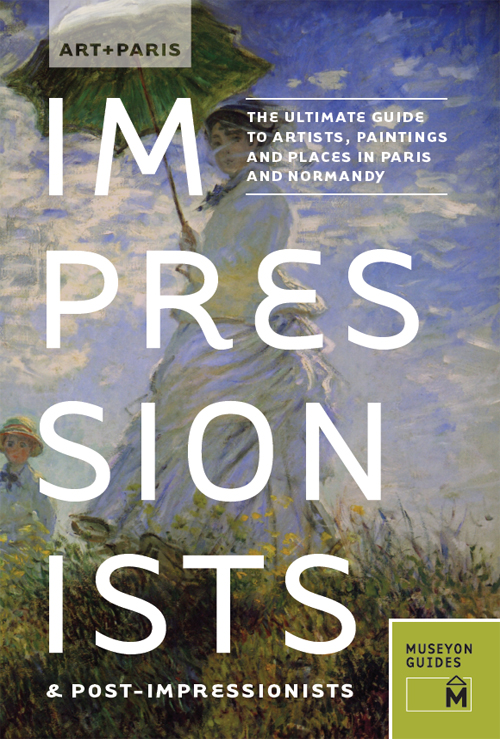

Cover image: Claude Monet, Woman with a ParasolMadame Monet and Her Son, 1875. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

FOREWORD

In 19th-century Paris, a group of artists made the brazen move to stand up to the establishment. Inspired by douard Manet, young artists including Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, dgar Degas and Paul Czanne, set out to make art on their own terms. Spurning the Acadmie and foregoing the official Salon, these artists paved the way for modern art.

At a time when the average working man made between 1,500 to 2,000 francs a year and an artist favored by the official Salon could sell his a single painting for even more, the Impressionists struggled to get even a few hundred francs for their work. Many of these artists lived on the verge of poverty, surviving only on handouts from patrons and friends. Though they struggled in obscurity for decades, those who survived through the turn of the century were vindicated with international success.

This book will take you into the lives of the core Impressionists and the artists who followed them. Not only will you discover the dramatic true stories of their struggles and triumphs, this book will take you to the real-life places where they lived and worked in Paris and beyond.

See the world through the artists eyes. Get inspired.

What Is Impressionism?

by Cindy Kang

On Thursday evenings, as the gas lamps were lit in Paris of the early 1870s, the smoky, dark-paneled Caf Guerbois became the center of boisterous artistic debate. Over cigarettes, strong coffee and weak beer, Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro and other friends from different art studios discussed the possibility of forming their own exhibiting corporation. They had had enough of the conservative taste and nepotism of the French art academy, which had rejected their paintings from the annual exhibition in Paris known as the Salon.

When their first exhibition opened in 1874, the group was called the Corporation of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers, etc. Of the unmemorable name, Renoir explained: I was afraid that critics would immediately begin talking about a new school. Despite the artists attempt to assert their individuality, the critics did indeed perceive a new movement, which they dubbed, derisively, Impressionism.

The bte noir and namesake of the exhibition was Monets Impression, Sunrise. A morass of thick, choppy brushstrokes of unblended blues, violets and shocking orange, Monets work was the opposite of academic paintings such as William Bouguereaus Nymphs and Satyrthe darling of the 1873 Salon. The latters glossy, highly-finished surface, titillating mythological subject and seamlessly layered and blended tones made Monets painting look like an insignificant, blurry sketch done in bright, vulgar colors.

The eight Impressionist exhibitions mounted between 1874 and 1886 showcased these artists radical technique and subject matter. Although each artist worked in an individual style, their shared engagement with modern developments in science, urbanization and new cultural influences led to a revolution in Western painting.

The Roots of Impressionism

Optical Theory

Drawing from new theories of optics derived from Hermann von Helmholtz, the Impressionists believed that the human eye encountered a scene as a field of pure colors. The brain then processed these colors to create an intelligible image. An Impressionist painting was therefore an attempt to recapture that primary sensation.

Thus, Monet instructed a student: When you go out to paint, try to forget what objects you have before you Merely think here is a little square of blue, here an oblong of pink, here a streak of yellow, and paint it just as it looks to you until it gives your own nave impression of the scene before you.

Paint in a Tube

Renoir once claimed, Without colors in tubes, there would be no Impressionism. Before the mid-19th century, artists either made their own paints for each work day or stored them in messy, smelly pig bladders. The invention of paint in metal tubes was a revelation for the Impressionists. They could now bring their easels outdoors and work on whole paintings for entire afternoons, instead of being tied to a studio to work on one section of a painting at a time. Tube paints allowed the Impressionists to seize their direct, fleeting sensations of light and atmosphere and completely dissolve form into touches of pure brilliant color.

Photography

The Impressionists reacted competitively to the development of photography in France in the middle of the 19th century. Photographys limited palette pushed them to emphasize color as a distinguishing feature of painting. Their sketch-like technique, which looked spontaneous and dashed-off, even though it was meticulous and deliberate, attempted to compete with the immediacy of a photograph.

Nevertheless, the Impressionists also borrowed some of photographys tricks. In Degass Place de la Concorde, the arbitrarily cropped man at the left and the blurry figures and horse in the background were all devices imported from photography to convey a sense of motion and the impression of a moment frozen in time.

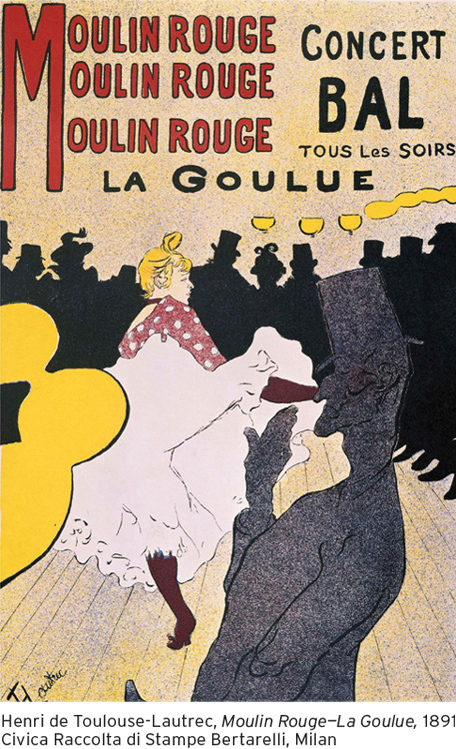

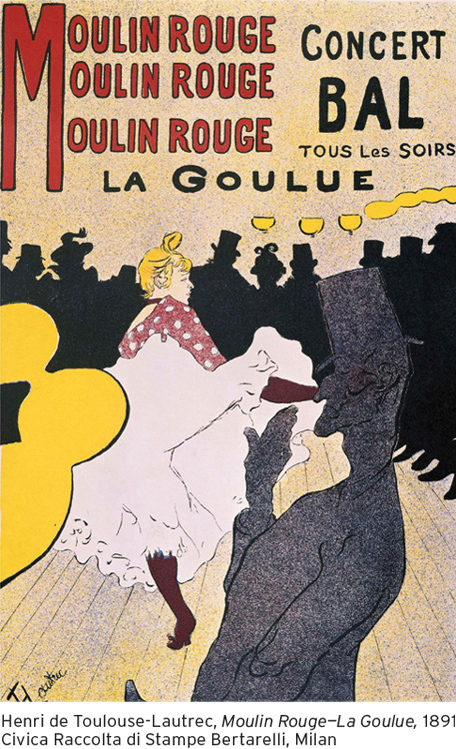

Japonisme

The formal innovations of the Impressionists were as much indebted to Japanese woodblock prints as to photography. The craze for Japanese art, dubbed japonisme, was launched by the exhibition of the Japanese pavilion at the 1867 Paris Universal Exposition. Japan had been closed to the West for the past two centuries and the influx of art from the East astounded the avant-garde artists. Degas was one of the earliest collectors of Japanese prints and Pissarro called the Japanese printmaker Hiroshige a marvelous Impressionist. The asymmetrical compositions, strong outlines, areas of flat color and aerial perspective found in works by Degas and Mary Cassatt were inspired by Japanese design principles.

Paris, City of Light

Wide, sparkling boulevards, lazy boats on the Seine, seedy cafs under lamplightthese everyday scenes painted by the Impressionists actually reveal the total transformation Paris experienced in the 19th century. Before Paris became the City of Light, it was a haphazard accumulation of old neighborhoods with narrow, meandering, sewage-filled streets. Emperor Napoleon III appointed the Baron Georges-Eugne Haussmann to raze the city and build orderly grands boulevards