First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Richard Hargreaves, 2011

ISBN 978 1 84884 515 2

eISBN 9781844686315

The right of Richard Hargreaves to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Chic Media Ltd

Printed and bound in England

by CPI

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

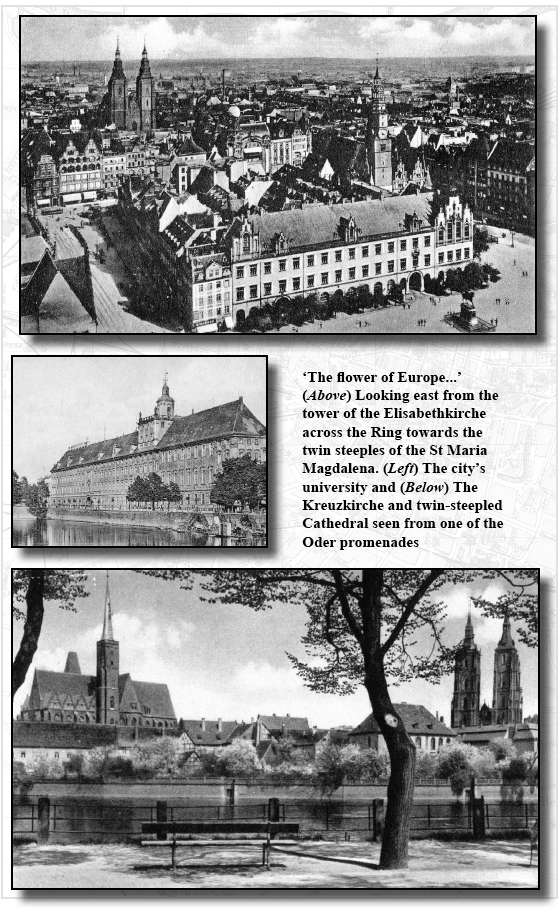

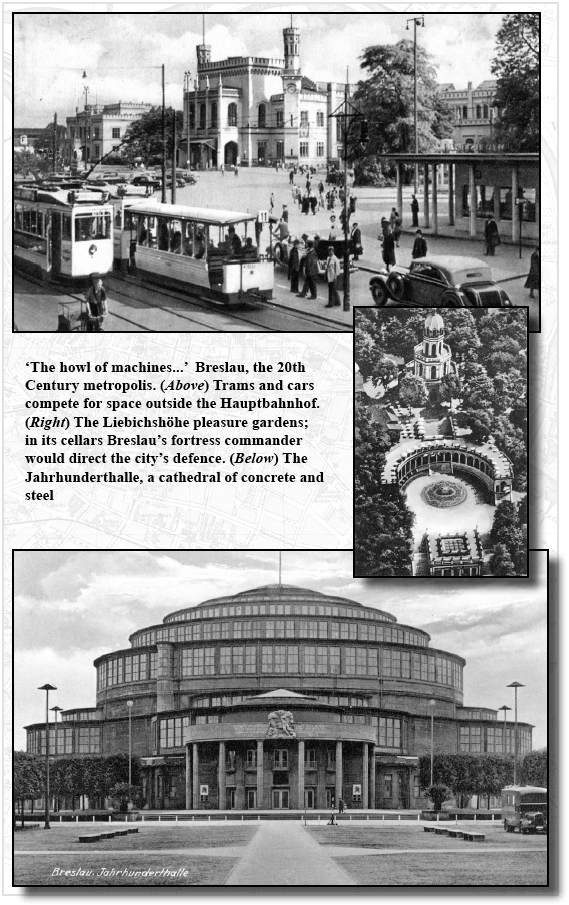

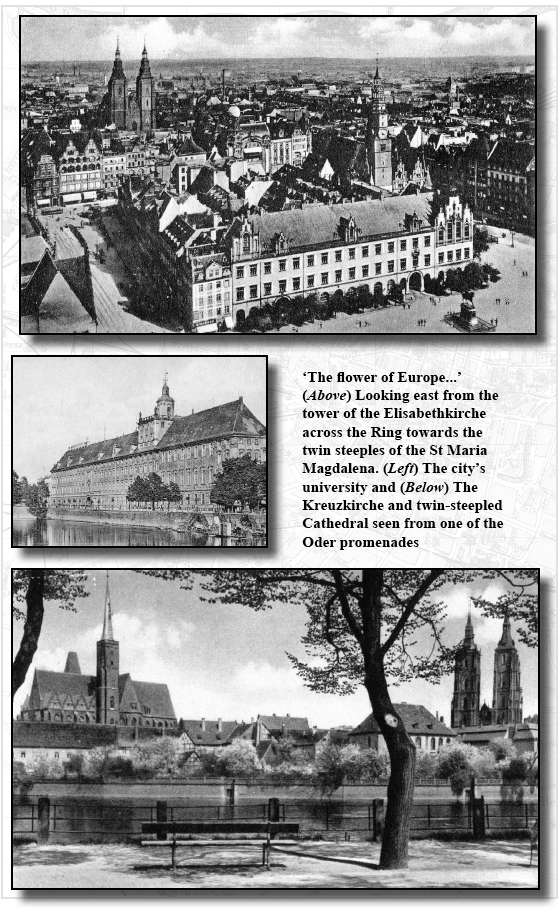

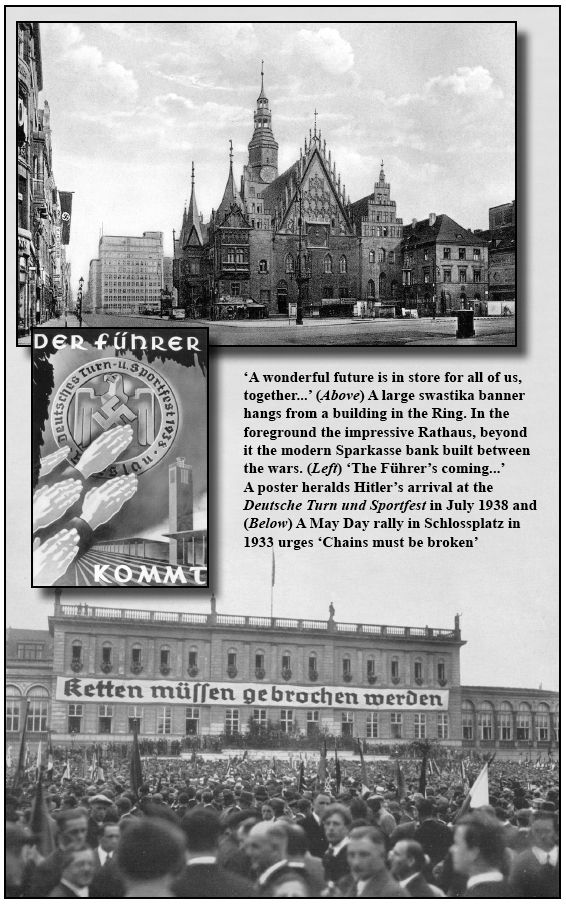

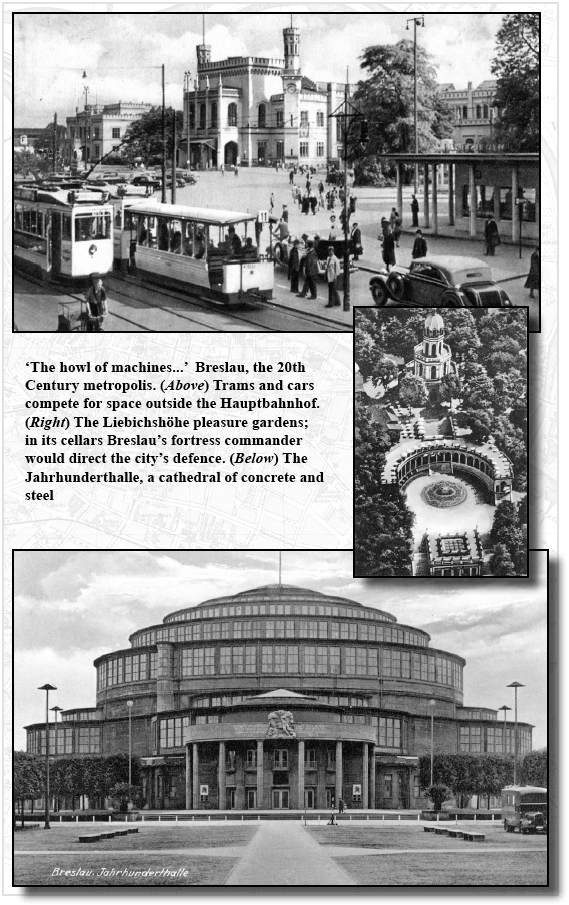

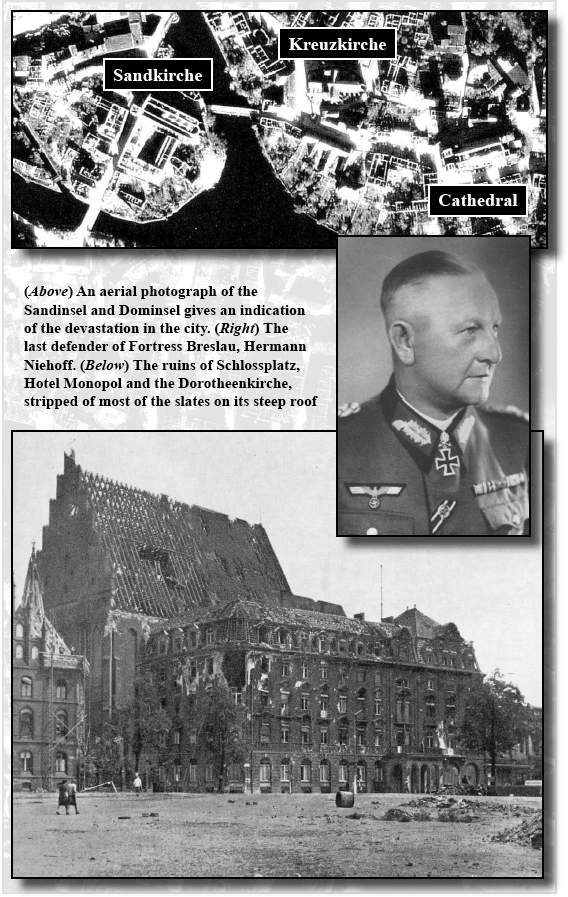

O n a summers day in Wrocaw, take a stroll along Ulica Marie Curie Sklodowskiej Marie Curie Sklodowskiej Street. Modern bendy buses with TV screens and electronic ticket machines vie for room on the suburban boulevard with clapped-out yellow coaches and trams which trundle east and west at regular intervals. After ten or so minutes you will cross the Most Zwierzyniecki Zwierzyniecki bridge which spans one of the countless arms of the Oder. It has stood here since 1897 there is an inscription celebrating the toil of the men who spent two years building it. But like all traces of the citys Germanic past, the plaque above the dateline has gone. Less easy to erase are the traces of battle; as with many of Wrocaws Oder crossings, Most Zwierzyniecki, is scarred by the bullets which struck it in the spring of 1945. Across the bridge you enter a district of avenues lined by trees. Ulica Marie Curie Sklodowskiej becomes Ulica Zygmunta Wrblewskiego the fourth title it has enjoyed in a century. On your right are the zoological gardens, on your left Ulica Adama Mickiewicza. Follow it for 150 yards until the trees part, revealing an alley leading to one of Wrocaws jewels: Hala Ludowa the Peoples Hall Max Bergs imposing colosseum of concrete and steel, built in 1913 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the German people breaking the shackles of Napoleonic rule. Tall columns, their plinths empty, lead down a sprawling concourse, dominated by a gigantic metallic spike or spire, the Iglica , erected in 1948 to celebrate Silesias return to Poland. To the left is a four-domed exhibition hall, latterly home to the Wytwrnia Filmw Fabularnych the factory of feature films. Four concrete modernist statues stand guard in front of it. The entrances are barred, the doors obliterated by Polish graffiti. The porticos cracked tile floor is covered with leaves, cigarette ends, sweet wrappers and other detritus. At one end of this seemingly forgotten porch is a huge tablet in a wretched state of repair, honouring the deeds of Polish soldiers who marched westwards with Soviet troops in 1944 and 1945 from the Bug to the Vistula, through Warsaw, through Pomerania, across the Oder and Neisse, and finally into Berlin. Turn around and you will find another huge stone inscription. A helmet adorned with a Red Star sits on a laurel wreath, chipped and discoloured, stained by more than six decades exposure to the elements. Beneath it a litany of Red Army victories: Moscow, Stalingrad, Kursk, Leningrad, the Ukraine, Byelorussia, Warsaw, Budapest and Bucharest, Belgrade, Vienna, Prague, and Berlin among them, plus the name of this city, Wrocaw. Like every monument, memorial and grave for the fallen of 1945, the gigantic tablets in the grounds of the Hala Ludowa are crumbling, decaying, overgrown, unloved, forgotten.

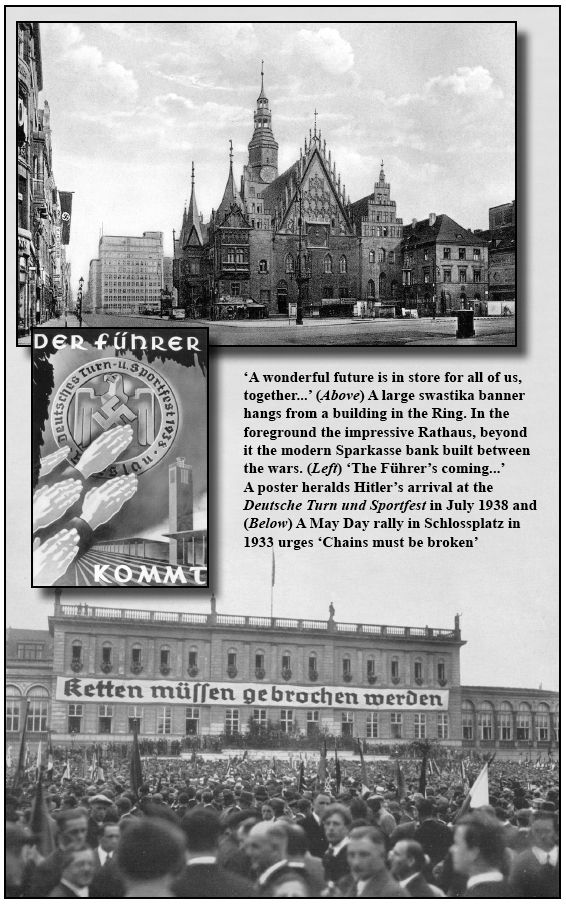

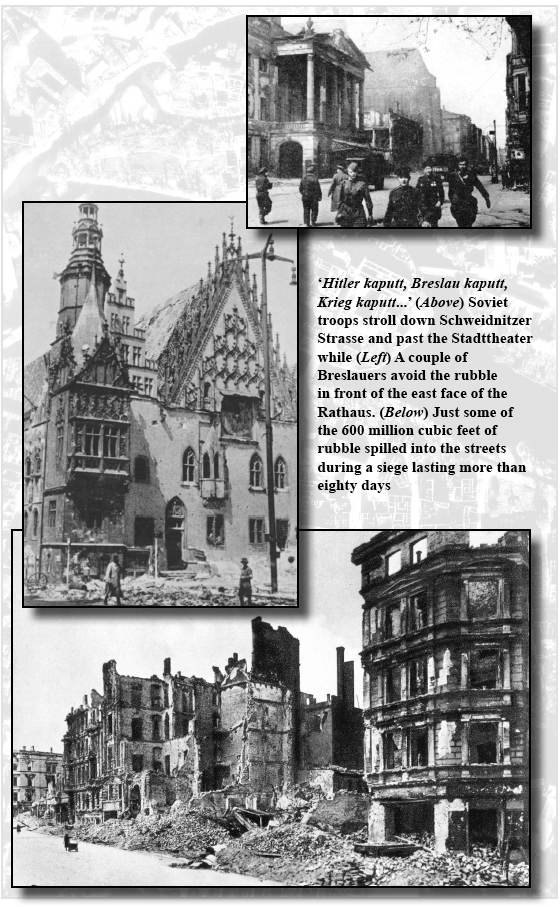

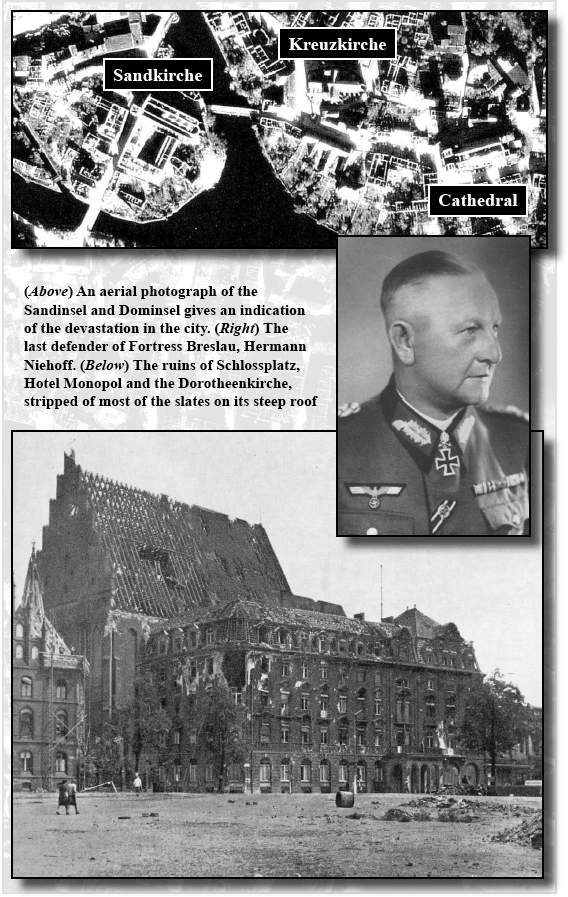

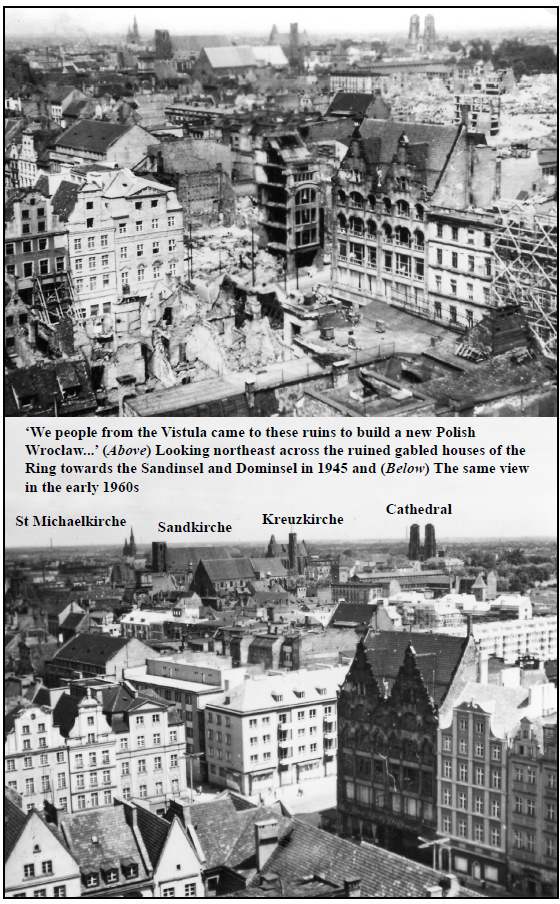

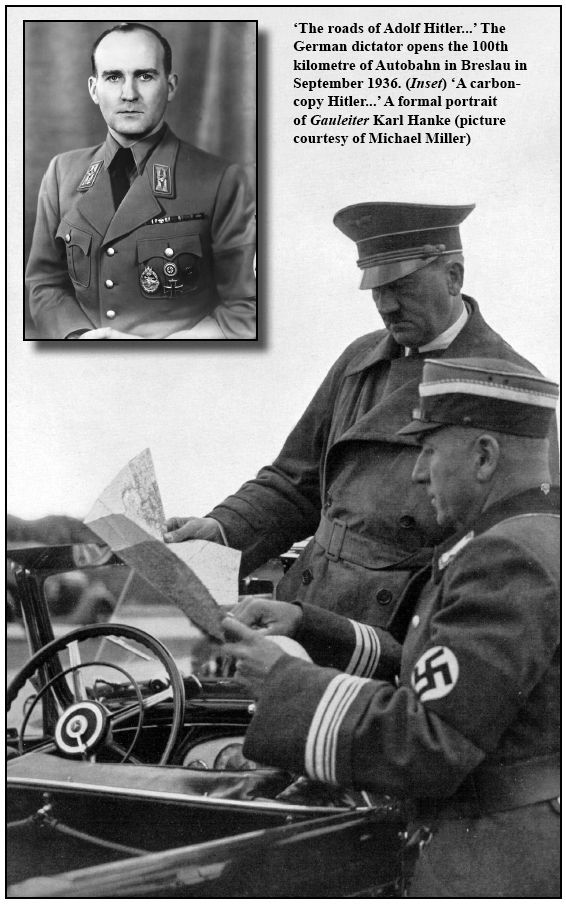

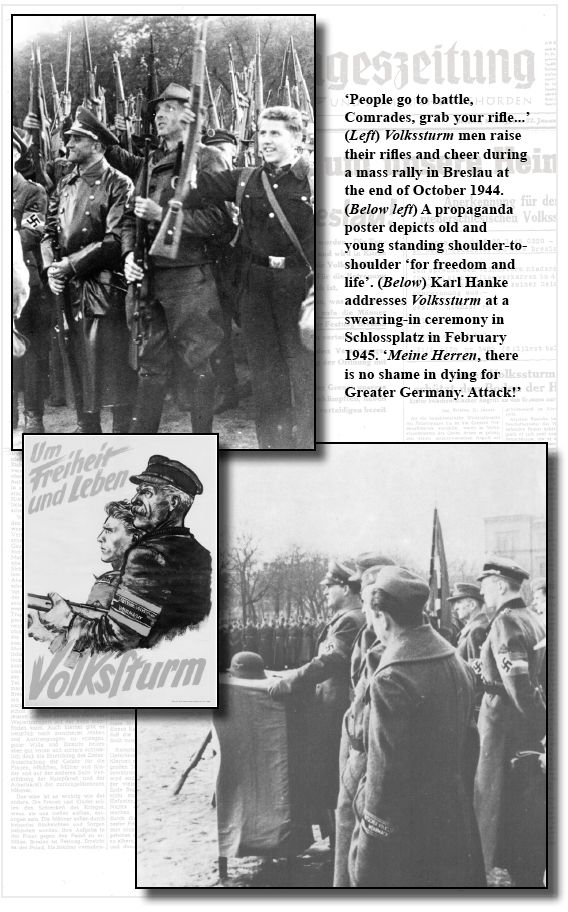

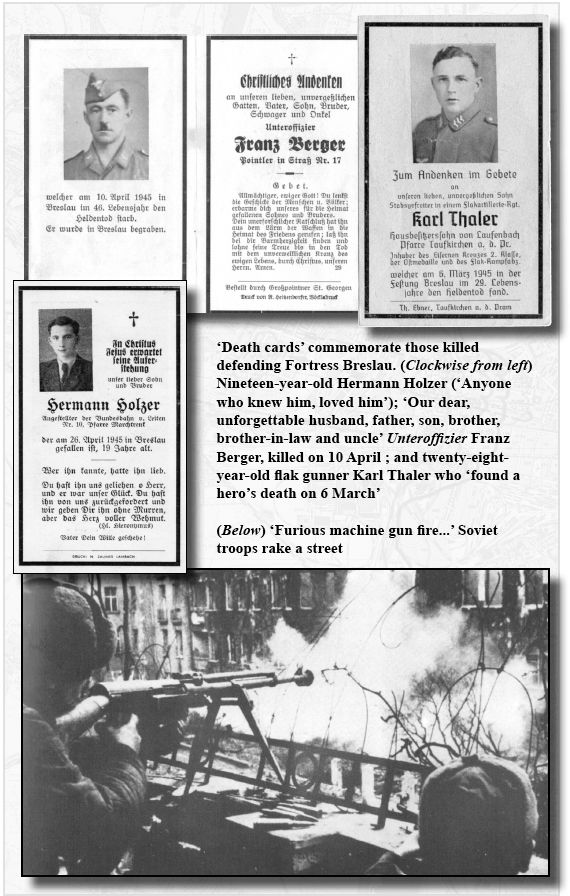

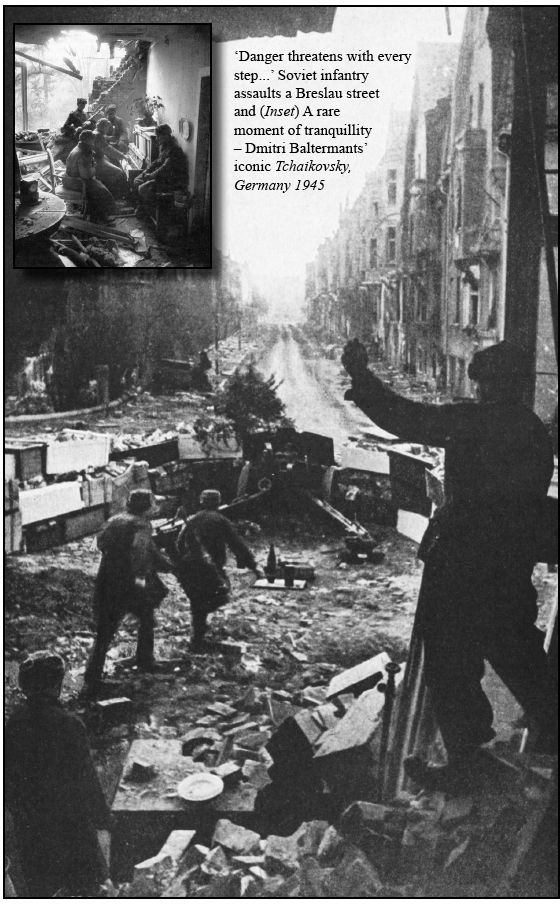

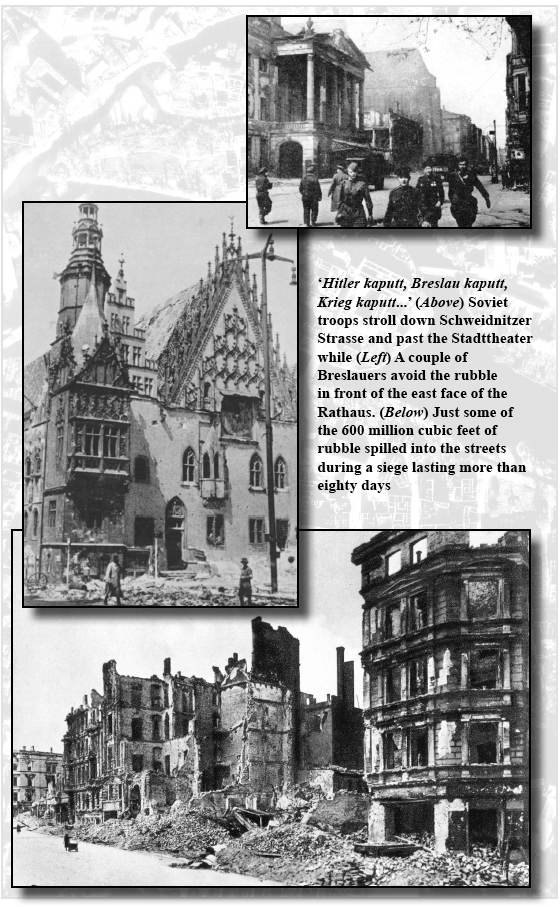

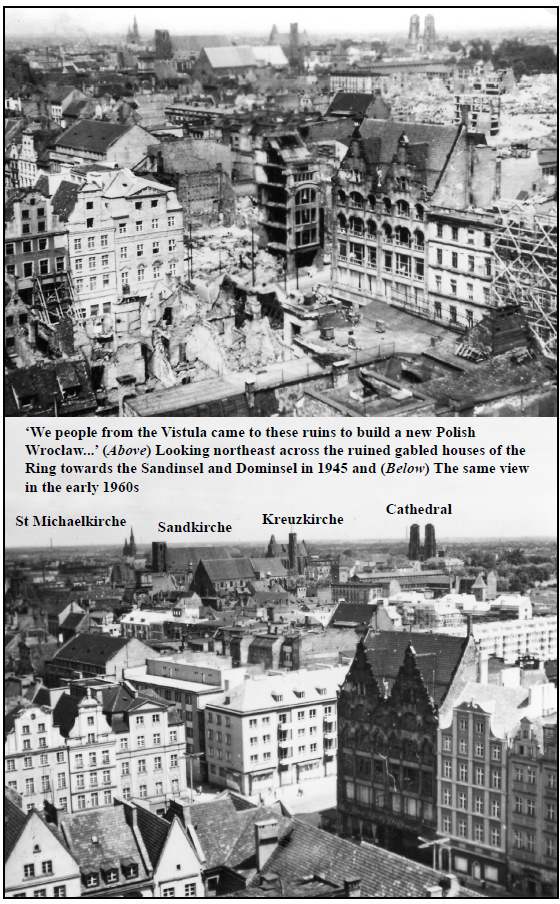

For once a terrible battle raged for this city. The siege of Breslau as it was then lasted longer than the battle for any other German city in 1945. The city was encircled for longer than Berlin (ten days), Budapest (sixty days), even Stalingrad (seventy-three days). It is a struggle which came to naught for the defenders. It achieved nothing, save to reduce a city, which was barely touched by war as 1945 began, to a ruin by the time it surrendered on May 6th. The devastation wrought was greater than in the German capital, greater than in Dresden that byword for destruction in World War 2 and as great as in Hamburg, another metropolis laid waste by Allied bombers. At least 18,000 of Breslaus population died in less than one week, fleeing the advancing Red Army in the depths of winter. A further 25,000 people soldiers, civilians, foreign labourers, prisoners were killed during the twelve-week struggle for Breslau. Nor does the story or the suffering end with the citys fall. For the German survivors, bitter fates awaited: for the soldiers, prison camps in the Soviet Union; for civilians, rape, plunder and starvation, and finally expulsion from their homes as Silesia became Polish and Breslau became Wrocaw. For Polish settlers many driven from their homeland like the Germans they displaced there were decades of toil and hardship as they struggled to rebuild the Silesian capital.