Also by Grant Hayter-Menzies

and from McFarland

Mrs. Ziegfeld: The Public and Private Lives of Billie Burke (2009)

Charlotte Greenwood: The Life and Career of the Comic Star of Vaudeville, Radio and Film (2007)

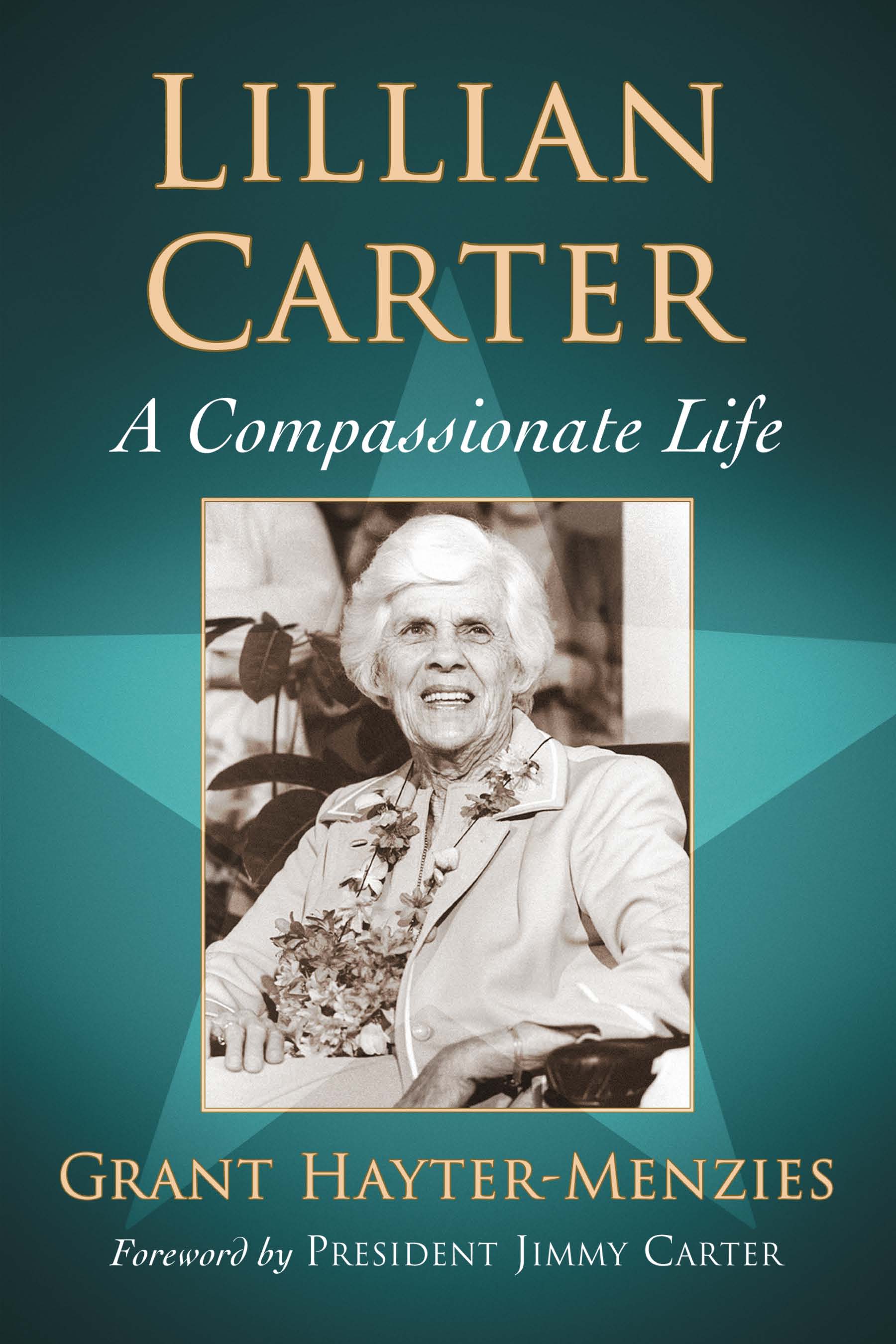

Lillian Carter

A Compassionate Life

Grant Hayter-Menzies

Foreword by President Jimmy Carter

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1933-0

2015 Grant Hayter-Menzies. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Lillian Carter on her return visit to India in 1977 (Peace Corps)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

In memory of my mother

and my grandmother

* * *

To Les and Freddie

with love

Foreword

by President Jimmy Carter

I had planned to spend my life as a career naval officer, but changed my mind when my father died. At his deathbed in 1953, I realized how he had been of benefit to so many people in our small town of Plains and decided to return home and emulate him in every way I could. His was an example that led me into local, state and national politics. My mothers life was changed just as profoundly.

She was a registered nurse, and she had devoted her service to the poorest people among our neighbors, many of them in black families. Unlike others in our segregated Southern community, she never honored the racial or cultural distinctions. My fathers death, while devastating to her, freed her to expand her life and to become everything she was meant to be.

As a widow, my mother embarked on a life of purpose which took her far from Plains. A seven-year stint as house mother at Auburn University for a fraternity rumored to be the most hell-raising of any in the state (her reason for choosing it) followed. Her fierce loyalty, ability to share a drink, and her unconditional affection stamped her in the hearts of every member of the fraternity. For Mother, looking after these young men was only the beginning. She then spent three years managing a nursing home for a friend, and in 1964 she became county campaign manager for President Lyndon B. Johnson, running a daily gauntlet of racist slurs scrawled across the sides of her Cadillac. In these fractious years, Mama was in her element.

Sitting up in bed watching television one night in 1966, Mamas attention was grabbed by an advertisement slogan for the Peace Corps that seemed to challenge her to action: Age is no barrier. At 68, Mother joined the Peace Corps and served as a public health volunteer in Vikhroli, thirty miles outside Mumbai. Assigned to work with untouchables (dalits), she dismayed upper caste Indians by doing the kind of work untouchables did. She treated leprosy patients, cleaned up human excrement, and confronted Indias own traditional segregation policies by openly eating and socializing with untouchables, at the same time introducing to these marginalized people the concept of equal rights for wives and daughters in and out of the home. She learned the languages and the belief systems of her hosts, reading the Baghavad Gita and talking with famous holy men. During those years in India, Mama went from middle-class white Southern woman with a fur coat and diamond rings to barefoot caregiver who, as she had done in Plains decades before, counted no costs in bringing medicines and medical care to people for whom few other people cared.

Mother returned to Atlanta in 1968 with ten cents to her name, so thin we were shocked at the sight of her. But she had changed inside as well as outside. She left part of her heart in Indiawith the rest of it she determined to dedicate her life to making the world a better place for all people not so fortunate as she.

Her energy and purpose grew with my political aspirations, from my governorship of Georgia in 1971 to my run for the White House in 1976. Mama became one of the Carter campaigns most formidable public relations weapons. As much a fixture in her rocking chair at the Plains campaign headquarters as she was stumping across the nation, rubbing elbows with the leading lights of show business and literature and domineering talk shows with her inimitable style, my mother saw the unimaginable become reality in 1976 when I was elected President of the United States. Through her influence as First Mother, she would see her personal humanitarian values put into global action. Mama not only called on governments to address racism, poverty and health care, but came out for gay rights at a time when few public figures had the courage to do so.

She also turned out to be a magnetic and effective ambassador. I often sent her in my place to far-flung locales to represent the White House; she toured African nations, where rulers rolled out red carpets for the white-haired lady in blue pantsuits, knowing she might find solutions to their problems. Her greatest overseas journey was back to Vikhroli in 1977, where the little gardeners daughter she had taught to read was a top scholar at her university (and one day a university president), and where Mama was celebrated by thousands who greeted her as Lilly behnour sister Lilly. When Rosalynn and I set up The Carter Center in Atlanta as an agency to support and protect human rights and as a neutral setting for conflict resolution, we called on Mother to advise us on medical care needs in third world societies. A crucial part of the Centers mission statementto be guided by a fundamental commitment to human rights and the alleviation of human sufferingcould be her lifes credo.

By the time she died in 1983, Mama had moved from personality to legendFirst Mother of the World, proclaimed the press. The Carter Centers partner, Emory University, established the Lillian Carter Center for International Nursing in honor of her work in India, while the Peace Corps created the Lillian Carter Award honoring outstanding senior volunteers. Numerous other awards and scholarships have been set up in her name. But above all, the ideals she fostered in her children on a remote farm in southwest Georgia continue to empower and inspire countless individuals through all the people she touched during her long life.

Not only was age no barrier to my mother. Her life was an example of how barriers of color, gender or creed were there to be broken. Dare to do the things and reach for goals in your own lives that have meaning for you as individuals, Mama wrote in 1968 from India, in a letter addressed to her children but just as applicable to children everywhere, doing as much as you can for everybody, but not worrying if you dont please everyone.

Mama lived not to please, but to heal.

Preface

I never met Lillian Carter in person. But long before I came to know her family or see the farm where she lived or the community where she nursed during the Great Depression, I was introduced to her through another woman who shared her ideals: my grandmother Nina.

Next page