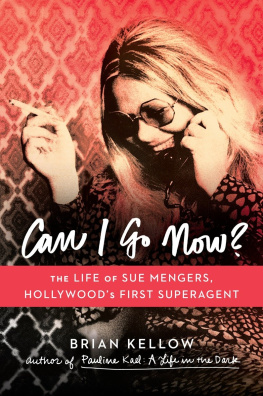

ALSO BY BRIAN KELLOW

PAULINE KAEL: A LIFE IN THE DARK

ETHEL MERMAN: A LIFE

THE BENNETTS: AN ACTING FAMILY

CANT HELP SINGING: THE LIFE OF EILEEN FARRELL

(WITH EILEEN FARRELL)

VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Copyright 2015 by Brian Kellow

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

A Word to Hostesses from The Love Letters of Phyllis McGinley. Copyright 1952 by Phyllis McGinley. Copyright renewed 1980 by Julie Elizabeth Hayden and Phyllis Hayden Blake. Used by permission of Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

PHOTOGRAPH CREDITS

Courtesy of Joanna Poitier:

Courtesy of Leo Sender:

Courtesy of Boaty Boatwright:

Gary Lewis/mptvimages.com:

Authors Collection:

Universal Pictures/Photofest:

Courtesy of Toni Howard:

ISBN 978-1-101-62052-6

Version_1

Contents

For Scott Barnes,

who shows me what it means to be Two for the Road

Introduction

It is difficult to believe that in the late 1950s or early 1960s, even in the hard-boiled, wised-up, seen-it-all world of show business, there were many secretaries like Sue Mengers. The era of Helen Gurley Browns Sex and the Single Girl had not yet arrivednot quite. Perhaps Rona Jaffe described this period most succinctly in the opening of her best-selling novel of 1958, The Best of Everything:

You see them every morning at a quarter to nine, rushing out of the maw of the subway tunnel, filing out of Grand Central Station, crossing Lexington and Park and Madison and Fifth avenues, the hundreds and hundreds of girls. Some of them look eager and some look resentful, and some of them look as if they havent left their beds yet. Some of them have been up since six-thirty in the morning, the ones who commute from Brooklyn and Yonkers and New Jersey and Staten Island and Connecticut. They carry the morning newspapers and overstuffed handbags. Some of them are wearing pink or chartreuse fuzzy overcoats and five-year-old ankle-strap shoes and have their hair up in pin curls underneath kerchiefs. Some of them are wearing chic black suits (maybe last years but who can tell?) and kid gloves and are carrying their lunches in violet-sprigged Bonwit Teller paper bags. None of them has enough money.

The Best of Everything is set in the world of book publishing, but in the world of Hollywood and the world of the New York theaterin virtually any field in the arts at that timewomen in subordinate positions were expected to behave in a fairly regimented way. Show up on time. Never complain about having to work after hours or on weekends. Never complain at all, in fact. Pay for your own taxi home. Treat your boss as if he were the center of the universe.

Sue Mengers did not come close to fitting into this rigid concept of a woman in the workplace during the Eisenhower and Kennedy years. I was a little pisher, a little nothing, making $135 a week as a secretary for the William Morris Agency in New York, she told Mike Wallace in her famous 1975 interview for a segment of CBSs 60 Minutes. Well, I looked around and I admired the Morris office and their executives, and I thought, Gee, what they do isnt that hard, you know. And I like the way they live, and I like those expense accounts, and I like the cars.... And I suddenly thought: That beats typing.

There is an Elizabethan term, self-panicker, meaning someone whose behavior is funniest of all to herself, and thus persuades everyone around her that she is the funniest person in their sphere. Sue Mengers might be called the ultimate self-panicker. Her rise through the ranks of the secretarial pool took place before the eras of Helen Gurley Brown, Rona Jaffe, Jacqueline Susann, Marlo Thomas as Ann Marie in That Girl, and Mary Tyler Moore as Mary Richards. Lionel Larner, who worked with Mengers at the agency Baum & Newborn in the early 1960s, remembered that on Monday mornings she would walk in, toss her purse down, throw her feet up on her desk, and proclaim, once she was sure she had the attention of the entire office, Sue had a tough weekend. Sues thingy hurts.

Sue Mengers, from the start, showed a remarkable gift for leveling with the actors and directors with whom she crossed paths. I remember coming into the offices of Baum & Newborn to get the sides for a new play, recalled actress Phyllis Newman. She was beyond fresh mouthed. Beyond! It was a tiny office and she was the everything girl. And I was up for some part and so was another client of Baum & Newborn. Sue said, Dont even bother going. Shes schtupping the director! I wasnt a prude at all, but it made me scream with laughter, even then! And she liked to get in those Rosalind Russell poses, with the leg up on the desk.

Unlike many women who learned to play the game as they advanced in the workplace, Sue Mengers, the first enormously successful female agent in the movie industry, remained throughout her career very much the woman she had always been. Her refusal to rein in her behavior became a kind of calling card; it made people sit up and take notice of her. She gave every appearance of being as shrewd, as cunning, as confident, as any of the most powerful people on the screenand more so than many of them. When one takes into account her rocky early yearswhat used to be described in fan-magazine articles as humble beginnings, it might make a very tidy argument that Sue Mengerss outward bravado was a mask for a deep-seated insecurity, a hidden belief that she did not really belong in the elite Hollywood circles that she so masterfully orchestrated. But those who knew her well do not feel that her blazing confidence was a mask or pose. The truth is somewhat simpler: she was a woman who prized a finite number of thingsproven talent, success and the ability to achieve it, wit, brains, wealth, social position, grit, integrity, beautyand something that used to be called moxie. She believed in these qualities so completely that she was generally dismissive of anyone who didnt possess them. The world according to Sue Mengers was divided into winners and losers, A-lists and B-lists. She devoted herself to being an A-list winner. She pulled no punches and made no apologies for the life she lived. Many years after she had cemented her reputation as the most colorful agent and most exclusive hostess in Hollywood, she commented on the glittering parties she threw, which were among the most coveted invitations in town. I never invited anyone who wasnt successful... I was ruthless about it. It was all stars. I would look around my living room at all of them and even Id be impressed with myself.

And yet as much as Sue Mengers threw a grenade into the conventional boundaries for women in show business, she was also, in certain ways, defined by that early Best of Everything view of women in the workplace. She believed that men were objects of sexual and financial gratification and that it was a womans place to master that particular dance to the best of her satisfaction. She believed that men were by nature feckless and undependable and that women needed to embrace that fact; it was up to women to figure out how best to manipulate them, to turn the automatic advantage men were born withthe lust for power and drive for financial success, the natural aggressiveness and competitivenessto womens advantage.