Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Popperfoto/Getty Images

Popperfoto/Getty Images

Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Topical Press Agency/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Ronald Dumont/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images

Central Press/Getty Images

Stanley Franklin/ The Sun /NI Syndication

, Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Anwar Hussein/Getty Images

David Levenson/Getty Images

PA/PA Archive/Press Association Images

Tim Graham/Getty Images

Martin Keene/PA Archive/Press Association Images

The Times /NI Syndication

Stefan Rousseau/AP/Press Association Images

Fiona Hanson/PA Archive/Press Association Images

PA/PA Archive/Press Association Images

Getty Images

Princess of Hearts

19261947

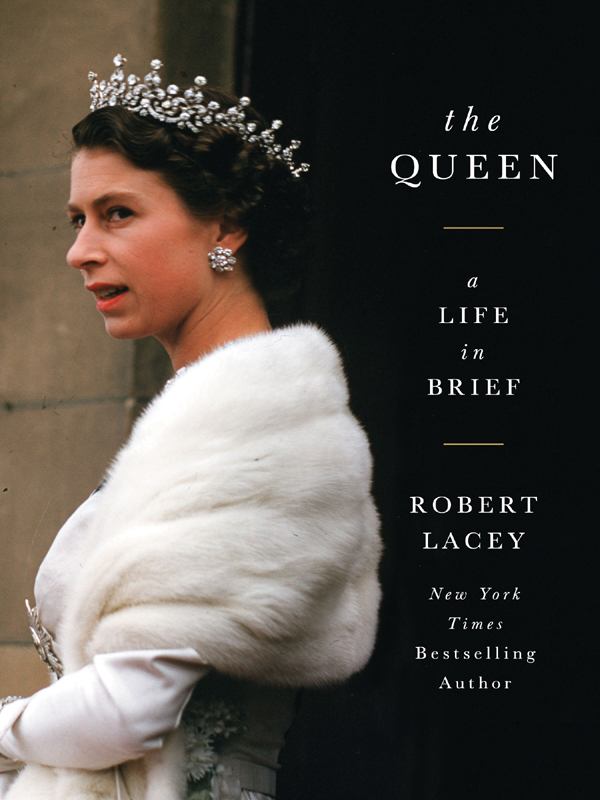

When the future Queen of the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, New Zealand and a dozen other Commonwealth countries was first learning to talk, she had difficulty pronouncing all the syllables in Elizabeth. Lilibet was the best she could manage, so that became the name by which her family knew her throughout her childhood and, in the case of her husband Prince Philip, to this daythough when hes feeling particularly affectionate, he also calls her Cabbage.

Little Lilibet loved to ride her tricycle. To judge from her tailored coat and sensible shoes, she might have been any well-born three-year-old pedalling the gravelled gardens of Mayfair at the end of the 1920s. Except that she called her grandfather Grandpa Englandand he lived across the park in Buckingham Palace.

Elizabeth of York was not born to be Queen. She came into the world on 21st April 1926, the equivalent of the modern Princess Beatrice: first-born daughter of the Duke of York, destined to flutter on the royal fringe. York is the dukedom traditionally given to the monarchs second sonPrince Andrew today and Elizabeths father, Prince Albert, in the 1920s. So while Lilibet was brought up with almost religious respect for the crown, there seemed no chance of her inheriting it. Her young head was never turned by the personal prospect of grandeurwhich is why she would prove so very good at her job. Elizabeth IIs lack of ego was to prove the paradoxical secret of her greatness.

Princess Elizabeth of York rides her tricycle in Hamilton Gardens, Mayfair. 1931

She grew up in no. 145 Piccadilly, a large, semi-detached London town house that was destroyed by German bombs in World War II and is now the site of the London Intercontinental Hotel beside the Hard Rock Caf. Her nursery was at the top of the house, stocked with dark, polished, grown-up furniture, complete with a clock and a glass-fronted display case. The night nursery in which she slept had no plumbingthere was a large jug and a basin holding water to wash her hands. On the landing outside the Princess took to collecting the toy horses on wheels she liked to ride around the house. Every evening she would change their saddles and harnesses before she went to bed.

We know these details thanks to Lady Cynthia Asquith and Anne Ring, confidantes of Elizabeths PR-conscious mother, the Duchess of York, who handed over family photographs and encouraged the ladies to write syrupy articles and books to feed the public appetite for intimate and authentic details of royal life. With royal sanction, the writers took their readers on a tour of the plum-carpeted premises of no. 145 so they could see the rocking horses on the landing and could almost touch the little scarlet dustpan and brush with which the Princess was taught to keep her room tidy. They were even invited inside the bathroom to imagine the naked splashings of a damp, pink cherub who seemed to be finding this bathing business the perfect end to what had been a perfect day.

With a voyeuristic emphasis on domestic furnishings, Lady Cynthia and Ms Ring developed a style of public intimacy which suggested that the Duchess of York had thoroughly absorbed her mothers opinions on royalty, fish and sea-lions. When it was let slip that the Princesss nursery clothes and trimmings were in yellow, other colours fell out of favour overnight. Until then customers at Selfridges of Oxford Street had had to order specially if they wanted something other than pink or blue for their children. Now almost every mother wants to buy a little yellow frock or a primrose bonnet like Princess Elizabeths, reported Americas TIME Magazine, which chose to put the Princess on its cover in April 1929 for setting a major fashion trend when she was only three.

The Royal Family doted on the little Princess as much as did the general public. When King George V fell ill with bronchial pneumonia early in 1929, his doctors prescribed recuperation in the bracing sea air of Bognor on the Sussex coast, and his granddaughter was sent down to aid his recovery.

G. delighted to see her, wrote Queen Mary in her diary at the end of March 1929. I playedin the garden making sandpies! The Archbishop of Canterbury came to see us and was so kind and sympathetic.

When the King got back to London he maintained that regular contact with his granddaughter was essential to his health and worked out that, before the leaves were on the trees in Green Park, he could actually see the front windows of no. 145 Piccadilly from Buckingham Palace. So every winter morning, soon after breakfast, the young Princess would draw her curtains and wave across the park, while her grandfather looked out for her and waved back.

On 21st August 1930 Elizabeth was joined by a younger sister, Princess Margaret Rose, who, at the age of three weeks, was described by her delighted mother as already possessing a will of iron to complement her large blue eyesall the equipment that a lady needs! The wayward consequences of Margarets iron will were to generate no little trouble and controversy in Elizabeths adult life, but in 1930 the immediate upshot of her arrival was rearrangement in the nursery. Elizabeths existing nanny Alla, Clara Knight, an elderly, square-jawed country woman who had served as nanny to the Duchess herself thirty years earlier, now took charge of the new arrival, leaving the four-year-old Princess to the care of her young Scottish assistant, Margaret Bobo MacDonald, the twenty-six-year-old daughter of an Inverness railway worker.

For the next six decades Bobo MacDonald was to become closer to Elizabeth than anyone else from outside her familyher most intimate companion and confidante. The plain-spoken young Scotswoman slept in the Princesss bedroom for most of her childhood then continued, as her dresser, to lay out her clothes every morning and evening in adult lifea legendary and rather feared power in the palace, credited with everything from her mistresss lamentably un-matching handbags to the Queens notorious frugality. The young woman who had grown up in a company cottage beside a railway line trained Elizabeth to save the wrapping paper from her presents after Christmas and birthdays, to be neatly smoothed and stored away in a special box, with the gift ribbon rolled up for future use.