Build Up for Battle

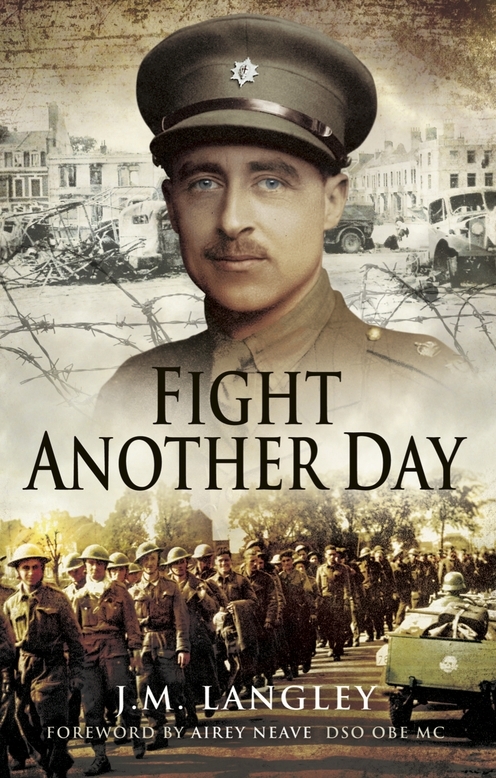

I do not know what you will do in life but at all costs avoid becoming a club or pub bore, my father would often say, adding, the worst are those who talk or write about themselves. It is largely due to the insistence of my children, who assure me I have a good tale to tell about how I passed the wartime years, that I have disregarded this excellent advice. It was my good fortune to be associated with a large number of men and women whose patriotism and courage went far beyond the call of duty and much of what I have written is a small token of my appreciation for all that they did.

War, as I saw it, was largely courage, suffering bravely borne, dogged determination to carry on in the face of disaster, and triumphs over the well nigh impossible. However, there were other less pleasing aspects incredible blunders, muddled and confused thinking, treachery and betrayal. I believe my experiences represent a fair balance between mens achievements and their failures; further, for good measure, it is leavened with humour which so often brightened even the darkest hour.

During the inter-war years a distinguished, if stupid, soldier of renown achieved notoriety by his oft-repeated statement, I recommended my servant for the VC because he followed me wherever I went. I do not fall into that category, though I must confess I thought that when I escaped from the Germans the whole business of getting back to England would be a matter of some congratulation; but I never imagined it would be regarded as an epic of courage and endurance, as it was by many. At the time it was useless to point out that as the Germans had acquired half Europe they had more problems on their plate than trying to catch one junior army officer, that running away hardly came into the category of bravery, and that travelling by train and hiding in hotels did not call for much endurance. I hold this view today, and indeed when I was asked if I would accept an offer to represent the escapers of the last war in the Association of POWs of the 1914 18 War I refused, solely on the ground that I was not a genuine escaper.

My activities in the second half of the war in helping escapers, or perhaps more accurately evaders, to return from enemy-occupied territory was more in my blood. At the outbreak of the First World War my father had given up a promising career at the Bar to join the South Staffordshire Regiment. He was wounded, and on recovering was appointed Assistant Military Attach in Berne. This, as I discovered many years later, was a cover for his work as a member of the British Intelligence Service. I doubt if he ever expected his son to follow in the same career.

I was in fact one of the war babies, and made my own small personal contribution by very nearly becoming a casualty on the home front a few weeks after my birth. A minor stomach operation was bungled by a young and inexperienced surgeon, and those in authority made the necessary arrangements for what they considered was inevitable. However, my mother took a different view and moved herself into the nursing home to what she called take charge.

I have never been able to obtain a clear and unbiased account of the subsequent battle with the matron. My mother would never go further than saying At least I saved your life, the look on her face and the tone of her voice indicating that the cost was high. Apart from survival, my souvenir of this event was a stomach scar which truly fitted a war baby, and through the years ahead excited the interest and admiration of doctors.

Early in 1918 the family joined my father in Switzerland, where we all remained for the rest of the war. When peace came we all returned to England. My father was full of confidence that he could take up where he had left off five years before; after all, the War to end all Wars had been won, and did not the greatest politician of the age talk of Homes for Heroes? Alas, as two generations of men and women who fought for Britain now know only too well, the nations gratitude is very short lived, and God is forgotten and the soldier slighted with the most astonishing rapidity.

A CAREER.

( The Bight Man in the Bright Place .)

You should see our son James!

You should just see our James!

As bright as a button, as sharp as a knife!

My wife says to me and I say to my wife,

Youll never have seen such a son in your life

As our jammy son, James.

He is now three years old;

Hes a good three years old;

When the fellow was two you could see by his brow

(At the age of a year, you could guess by the row)

That this was a coming celebrity. Now

Hes a stout three-year-old.

Question: What shall he be?

Tell us, what shall he be?

Shall he follow his father and go to the Bar,

Where, passing his father, hes bound to go far?

But one knows, says his mother, what barristers are.

Something else he must be!

Do you fancy a Haig?

Shall our James be a Haig?

The War Office tell me hes late for this war,

Have the honour to add there wont be any more

Since thats what the League of the Nations is for;

So its off about Haig.

But his mother sees light

(Mothers always see light).

This League of the Nations we mentioned above,

With the motto, Be Quiet, the trade-mark, a Dove,

Will be wanting a President, wont it, my love?22

Jimmys mother sees light.

Yes, that could be arranged;

Nay, it must be arranged.

In the matter of years Master Jimmy would meet

Presidential requirements. What age can compete,

In avoiding the gawdy, achieving the neat,

With forty to fifty? Thus, forty-five be t.

Given forty-two years, hell be finding his feet

And the Treaty of Peace should be getting complete ...

And so thats all arranged.

HENRY.

My father was probably better off than a million or more others, since as a contributor to Punch he had achieved considerable success with his Watchdog series of humorous despatches from the trenches. He also wrote a number of amusing poems, one of which, A Career, was to prove over optimistic!

However, the next six years was a hard, relentless struggle to rebuild a shattered career, and it was not until 1925 that he was on the road to success and able to launch me on the educational programme as accepted by the professional classes of the time: preparatory and public schools followed by university.

My particular preparatory school, Aldeburgh Lodge, was situated at Aldeburgh in Suffolk, later to become famous for its Festival. The school had the simple aim of training boys for the public schools from which, it was confidently assumed, they would go on to be leaders within the British Empire. The theme was service to God, King and Country, which required unquestioning obedience to those in authority, a stiff upper lip and a goodly measure of play up, play up and play the game. Discipline was strict but just and the only thing I really disliked was the food.

It is, however, an ill wind that blows nobody any good as the following conversation in 1946 with a colleague who had survived three years on the Burma railway as a Japanese POW shows.

It was absolutely bloody, I suppose. Youre lucky to be alive.

Yes, I owe my survival largely to Aldeburgh Lodge.

How come?

The Jap food was better. I used to say to myself every day you survived Aldeburgh Lodge food and therefore you will not have much difficulty in surviving here.

All in all I look back with gratitude to my four years at Aldeburgh Lodge, where, though never happy, I received a training that was to prove of immense value in life ahead, and a sense of pride in ones country. Empire Day was a whole holiday and our heroes were Captains Scott and Oates, Admiral Nelson and Nurse Edith Cavell; our poetry The Charge of the Light Brigade and How Horatius held the Bridge; our music Land of Hope and Glory and Onward Christian Soldiers. Better than film stars, footballers and pop music? I still think so! Tough and active both physically and mentally, the headmaster expected the same from others. You must do something in life. In the churchyard over one grave there is the following epitaph He did no harm, neither did he good What a miserable life. Do something, if you only kill your mother at least you will have done something. But do not tell your mother my advice! Strong medicine for the young.