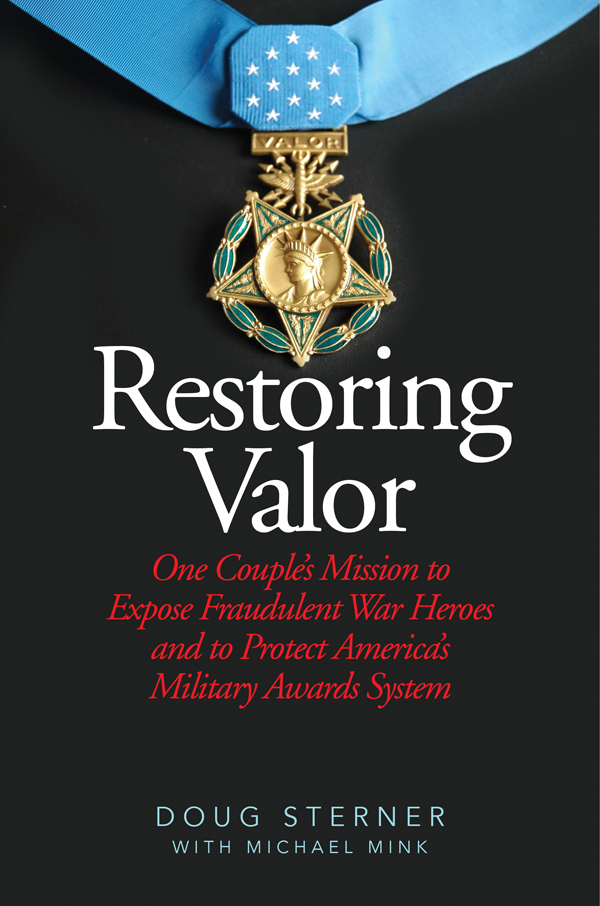

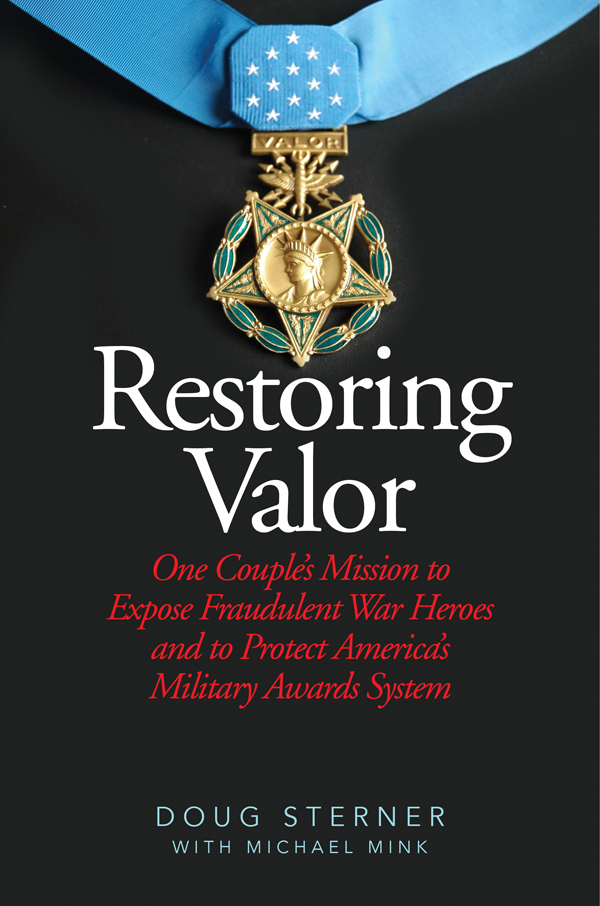

Copyright 2014 Doug Sterner

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eISBN: 978-1-62873-914-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

ISBN: 978-1-62636-551-3

Printed in the United States of America

Respectfully dedicated to those who

blazed the trail for us:

Mitchell Paige, MOH (USMC)

Special Agent Thomas A. Cottone Jr. (FBI)

B. G. Jug Burkett

Chuck and Mary Schantag

Contents

Introduction

Was the man who told such unbelievable tales exactly that: unbelievable?

Arizona Range News reporter Steve Reno could not believe his good fortune as he prepared to write a Veterans Day feature for his local paper in Willcox, Arizona.

Seated across from him in his office was a young man whose story would have been unbelievable were it not for the documents, photos, memorabiliaeven a chunk of marble from Saddam Husseins palacethe war hero provided to back up his story. Nearly two full pages in the November 10, 2004 edition of Staff Sergeant Gilbert Velasquezs hometown newspaper were needed to chronicle his service, his sacrifice, his uncommon valor, along with his suffering over two decades of military service.

According to Velasquez, after graduating from high school in Willcox in 1989, he enlisted in the US Army and was deployed to Iraq the following year to serve in Operation Desert Storm. After attacking Baghdad, his artillery unit of the 1st Infantry Division was joined by Green Berets, in the campaign to take the city of Tikrit.

Then we were told to go back to Baghdad because we had Saddam cornered. We started firing on January 27 [and] we stopped firing on January 30 at 4:15 on orders from General Norman Schwarzkopf. We were one quarter mile out of the city when they called the cease-fire, he was quoted as saying in the story.

Two years later, according to Velasquez, at the suggestion of his commanding officer he applied for and received both Airborne and Ranger training. He said that this career change landed him in Somalia in October 1993 for the tragic battle subsequently detailed in the movie Black Hawk Down.

I declined to talk to Hollywood, Velasquez told Reno of the making of that movie. The military didnt want us to talk about it. I did not give any interviews. It still hurts me bad to think about Somalia, but Ive made my peace with it. Noting his frustration with false propaganda Army accounts of that battle, he told Reno that after he lost three men, I had to go to the mens families and tell them it was a training accidentAfter I got out of the Army, I told the families exactly what happened. One of the wives slapped me and I had to regain my composure because I was crying with her.

After the 1993 Somalia battle, Velasquez considered leaving the Army but instead soon found himself in Haiti, battling native insurgents in efforts to insure that food and humanitarian relief reached the population. Following that duty he returned home, married, and hoped his obligation to his country had been fulfilled.

Fifteen days after the September 11, 2001 attack on the Twin Towers in New York City, Velasquez and his Ranger comrades were back at war, this time in Afghanistan. Of those combat patrols in the earliest days of the global war on terrorism he noted, I was going through a pair of boots every forty days on that rough terrain.

Velasquez described how he returned from Afghanistan in 2003 but his respite from foreign battlefields was short-lived. On March 20, 2003, the United States and coalition forces invaded Iraq in Operation Iraqi Freedom. Army Ranger, Staff Sergeant Gilbert Velasquez, was among them (or so he claimed).

Early in the campaign, Velasquez volunteered for a special mission with troops of the 101st Airborne Division against a high level target in Mosul that subsequently led to a fierce, four-hour fire fight. From it we found the two deceased bodies of Uday and Qusay, sons of Saddam Hussein. There were over 100 bullet holes in each of them. We put them in body bags to be cleaned up for pictures. I took a few pictures myself, he told Reno.

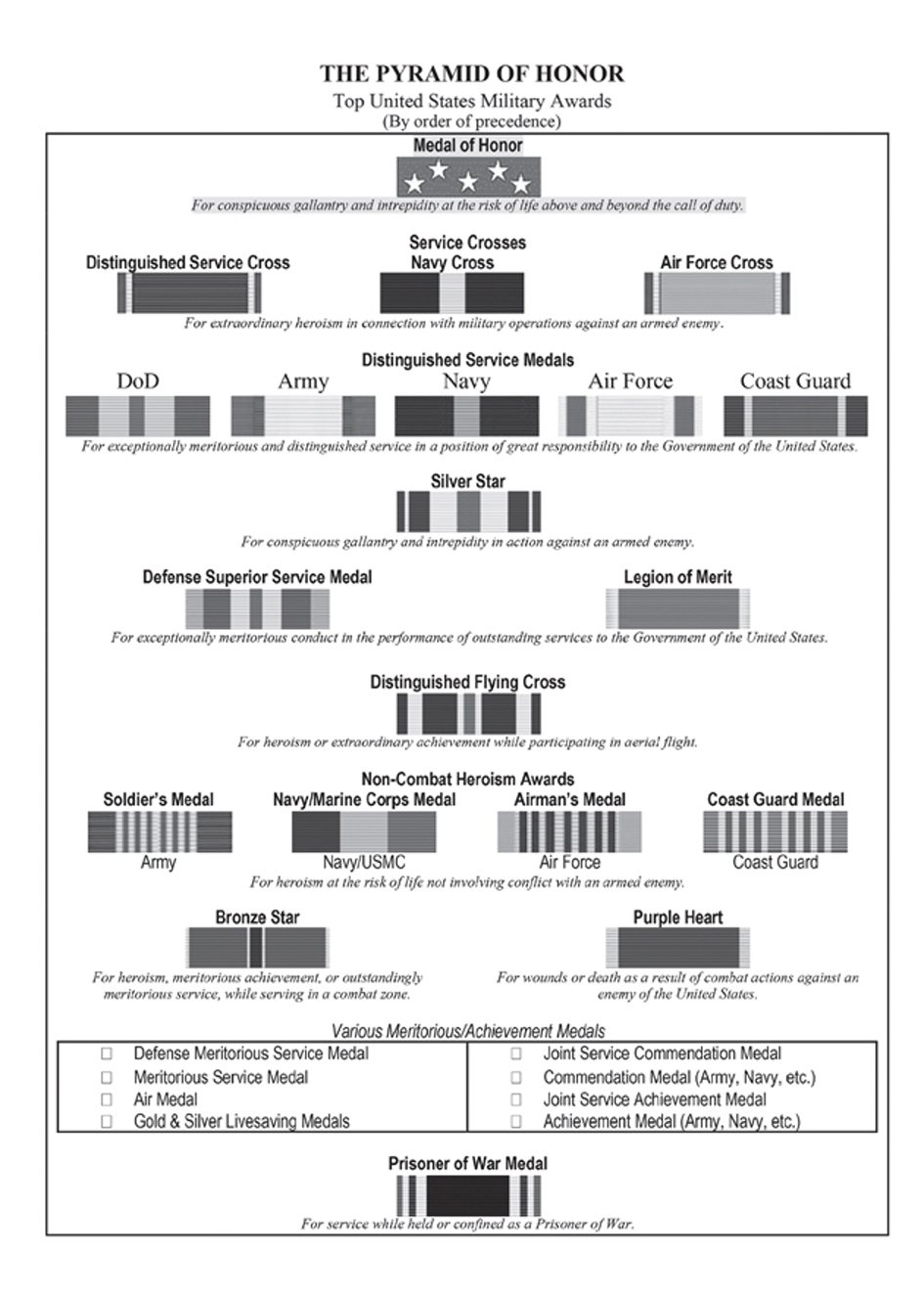

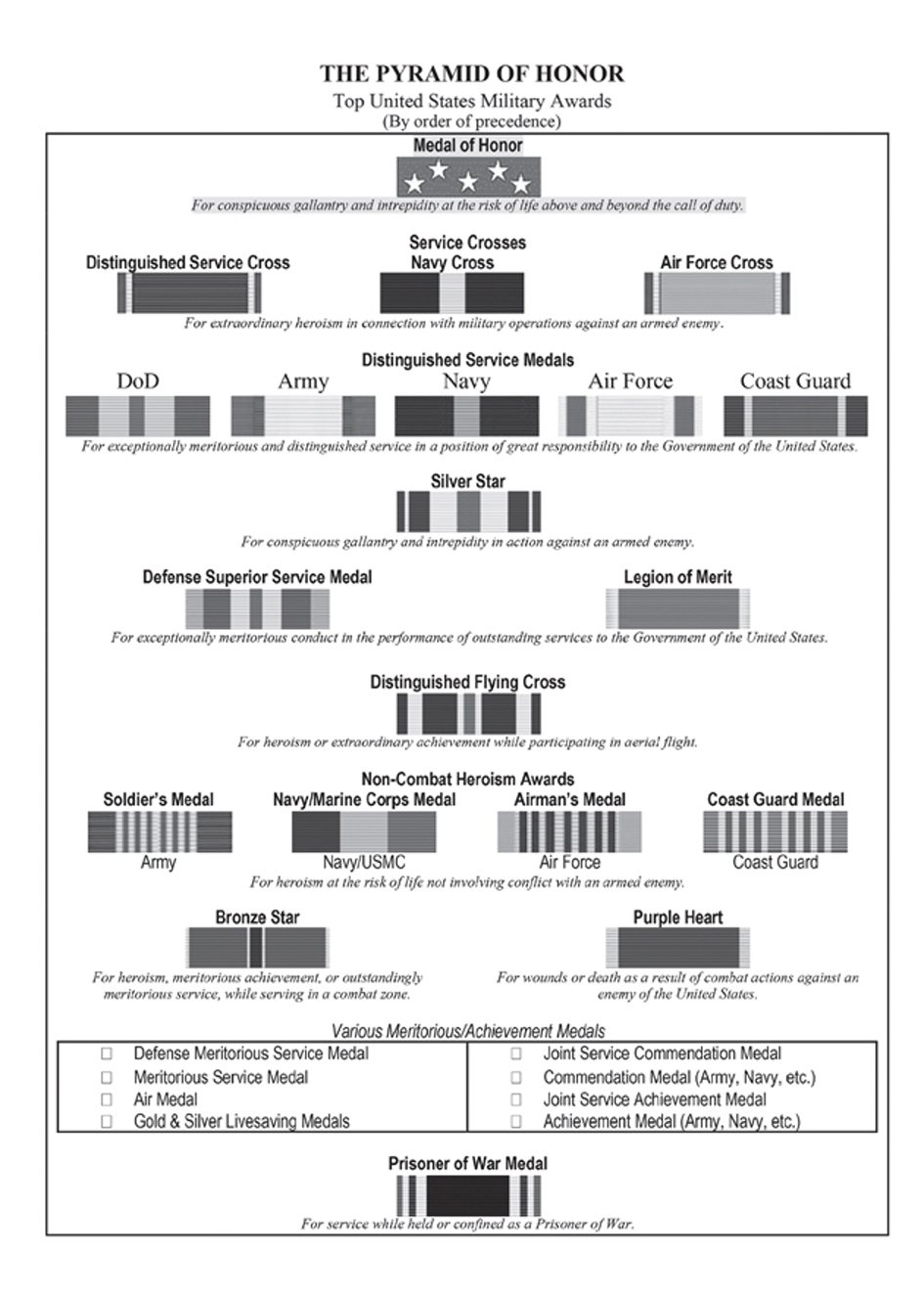

In other combat actions that followed early in the Iraq War, at one point when his men were pinned down by an enemy tank, Velasquez destroyed it and was awarded a Silver Star, the Armys third highest award for valor in combat. Then, in a subsequent battle he pulled his chief out of danger before going back and firing on enemy soldiers, killing six and earning the prestigious Distinguished Service Cross, which is second only to the Medal of Honor.

The best was yet to come.

In December 2003, while operating with 610 other soldiers in searches north of Tikrit, Velasquez related how one of his men saw a blanket in a field of corn that looked oddly out of place. I said we need volunteers and we took seven soldiers to that place, he remembered. Pulling back the blanket to reveal a pit in the ground, Velasquez shouted for anyone inside to come out with their hands up. A single man emerged from the pit. Velasquez told Steve Reno, As soon as I saw his eyebrows, I knew we had Saddam.

When Gilbert Velasquezs story ran in the Arizona Range News on November 10, 2004, the day before Veterans Day, the war in Iraq was only a year-and-a-half old, and was still supported by most Americans. Velasquezs story was one of the first detailed accounts of heroism from that war. His achievements made him one of the most-decorated heroes since the end of the Vietnam War, a period during which only a handful of Silver Stars had been awarded. Further, not since the end of the Vietnam War had any other American been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Armys highest award for valor and a decoration second only to the Medal of Honor.

The front page that was headlined HIGHLY-DECORATED SOLDIER TALKS ABOUT IRAQ, AFGHANISTAN, KUWAIT AND SOMALIA featured a large color photograph of Velasquez holding a framed set of medals. These included his Silver Star, the Legion of Merit, Bronze Star, Purple Heart and other decorations. He noted for the record that his Distinguished Service Cross, absent from the collection, had been buried with his godfather, a fellow soldier and mentor who had died in the War on Terror.

No doubt Steve Reno had every reason to feel fortunate to have elicited this incredible story from Velasquez, a hometown boy and reluctant hero who had served long, suffered much, and given a full measure of devotion to his country. Initially it was hard to believe such a highly decorated hero, this man who got Saddam, was from a community that was only now learning about his exploits on foreign fields of combat. Reno noted in his published story, His children would love to tell his story at school, but he has told them not to. The other kids will ask too many questions that my kids dont know the answer to.

Next page