This paperback edition published by Verso 2015

First published by Verso 1983

First published by New Left Books 1976

Norman Geras 2015

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-871-7

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-873-1 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-872-4 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Contents

To my mother and father

Foreword

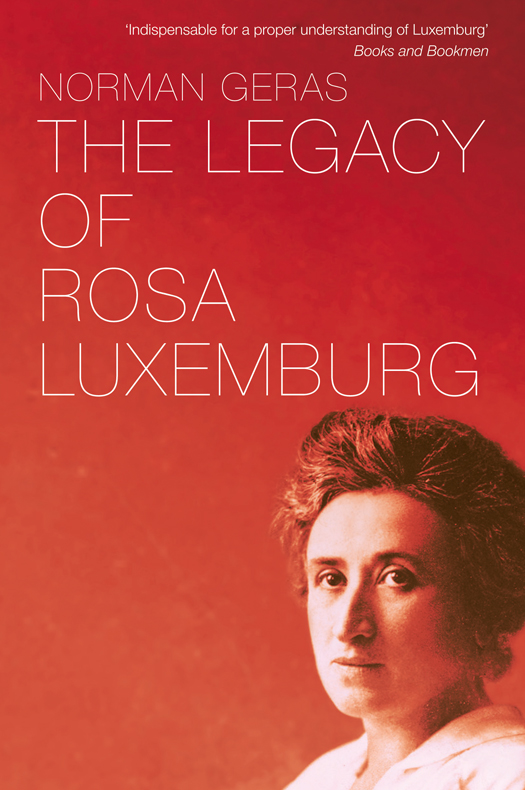

This book brings together four essays on the political thought of Rosa Luxemburg. Some brief remarks on their scope and content are in order here to identify the common set of concerns that has motivated the writing of them. The first essay examines the relationship to Luxemburgs political ideas of her economic theory of capitalist breakdown and disputes the widespread notion that the latter was the basis for a spontaneist conception of the class struggle. In the second essay, her contribution to the debate after 1905 over the nature of the Russian revolution is elaborated, against a common misconception of it, and some of the issues at stake in this debate, including her own views on the nature of bourgeois democracy, are assessed. Building on the point established by the first piece, the third argues that her strategic conception of the mass strike embodied not some irrational faith in mass spontaneity, but the elements of a theory of the political preconditions for successful proletarian revolution, as well as a first adumbration of the difference between bourgeois democracy and socialist democracy. The fourth essay takes up this last question directly, in connection with Luxemburgs criticisms of the Bolsheviks in 1918, and by way of a critique of the kind of interclass and libertarian conceptions which have been used so often to counterpose her to revolutionary Marxism. The first two essays have appeared previously in the New Left Review, in the issues for November/December 1973 and January/February 1975 respectively; the last two were written since then.

Apart from the substantive links connecting the topics of these essays, they are unified by three further considerations. In each case on capitalist breakdown, on the nature of the coming revolution in Russia, on the mass strike, on socialist democracy one is dealing with a question where Luxemburg has been badly misunderstood and where the effort of simple recovery is far from complete. Secondly, each of these questions has a historical significance extending beyond the boundaries of her own specific meaning, because in fact each of them formed the centre of a major politico-theoretical controversy in the history of the international workers movement. They are matters of interest to anyone interested in this history. Thirdly, they are matters that have not lost their currency but that have, on the contrary, continued to be important. The diagnosis of the tendencies of capitalist development and the articulation to it of a strategy for socialism; the nature of revolutions outside the advanced capitalist countries and the relationship of democratic to socialist tasks; the place of extra-parliamentary, mass struggle in the battle for socialism; the nature of socialist democracy these are all questions that remain, in one sense or another, open. They continue to be debated amongst socialists today and a great deal hinges on the answers to them. In that sense, to speak of Rosa Luxemburgs political legacy is not to consign her to a vanished past, as more than one non-Marxist writer has wanted to. It is to emphasise the actuality of her thought, and to try to appropriate to the present the most valuable elements of it. One does not have to think that her work is beyond criticism, nor is that the spirit of these essays, in order to believe that there are things in it of lasting value.

It is such a belief, and certain inadequacies in the existing literature about her, which together constitute the raison dtre of this book. More perhaps than other great revolutionaries, in any case at least as much, Luxemburg has suffered from the usual combination of misunderstanding with outright distortion. In her own case, it succeeded in burying her real political positions in relative obscurity for several decades after her death. Recently, this situation has begun to change for the better and there is today a growing body of serious literature about her. For the English reader in particular, access to her thought has been made immeasurably easier in the last ten years by the appearance of three different though overlapping collections of her political writings, by the publication of one new biography and the republication of an older one long out of print, by the first translation into English of several items of importance from Luxemburgs own Anti-Critique to Lukacs History and Class Consciousness. Nevertheless, in this matter as in others, the weight of the past is not easily shifted, and her work remains even now the subject of wild assertion and arbitrary or mistaken imputation. In the approach to her ideas there is often, even amongst serious students of them, a lack of analytical care and an insufficiently rigorous regard for the detail of her formulations. All of this helps to explain why there should be in both the structure and the style of the following essays the similarity that each presents and assesses some aspect of Luxemburgs political thought through a critique of misconceptions which are documented by reference to the existing literature. That similarity reflects something of the posthumous fate of her work. It goes without saying that this book is also indebted to the same body of literature, and every effort has been made to record that debt as well. It is also needless to say, given the very form of the book, that it makes no pretence to being an exhaustive treatment of her life or ideas. It is intended only as a contribution to clarifying them.

I should like to thank Michael Lowy, Robin Blackburn and Perry Anderson, who at various times discussed various points with me as well as giving me encouragement. More especially, I should like to express my gratitude to Adle Geras who, stage by stage, and more or less line by line, went through the writing of this book with me. Responsibility for its contents remains, of course, my own.

Manchester, December 1975

I

Barbarism and the Collapse of Capitalism

Capitalism, by mightily furthering the development of the productive forces, and in virtue of its inherent contradictions, provide(s) an excellent soil for the historical progress of society towards new economic and social forms. Rosa Luxemburg

No medicinal herbs can grow in the dirt of capitalist society which can help cure capitalist anarchy. Rosa Luxemburg

In her work we see how the last flowering of capitalism is transformed into a ghastly dance of death. Georg Lukacs

Amongst the misconceptions by which Rosa Luxemburgs thought has been deformed, the most widespread and tenacious is, without doubt, that which attributes to her a thesis going variously under the names of determinism, fatalism and spontaneism. Any one of a number of her real or alleged views can be cited as the manifestation or consequence of this thesis: her emphasis on mass spontaneity; her underestimation of the importance of organisation and of leadership; her belief that class consciousness is the simple and direct product of the class struggle of the masses. But what is generally regarded as its ultimate source and cited as definitive proof of its existence is her theory of capitalist breakdown, according to which the contradictions of capitalism must lead, eventually, but also automatically and inevitably, to its complete collapse. Now, there are problems about the very meaning of this notion of final collapse and these will be taken up later on. For the moment it suffices to record that its attribution to Luxemburg is perfectly well founded, for the notion is integral to her thought.