BLACK LABOR, WHITE SUGAR

BLACK LABOR, WHITE SUGAR

CARIBBEAN BRACEROS AND

THEIR STRUGGLE FOR POWER IN THE

CUBAN SUGAR INDUSTRY

PHILIP A. HOWARD

Louisiana State University Press

Baton Rouge

Published by Louisiana State University Press

Copyright 2015 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing

Designer: Barbara Neely Bourgoyne

Typeface: Quadraat

Printer and binder: Maple Press

Portions of chapters 13 appeared in somewhat different form in the authors article Treated like Slaves: Black Caribbean Workers in the Modern Sugar Industry, 19101930, Journal of Caribbean History, nos. 12, 2014, and are reprinted by permission.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Howard, Philip A., 1957

Black labor, white sugar : Caribbean braceros and their struggle for power in the Cuban sugar industry / Philip A. Howard.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8071-5952-1 (cloth : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-0-8071-5953-8 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8071-5954-5 (epub) ISBN 978-0-8071-5955-2 (mobi) 1. Sugar workersCubaHistory. 2. Foreign workers, HaitianCubaHistory. 3. Foreign workers, JamaicanCubaHistory. 4. Sugarcane industrySocial aspectsCubaHistory. 5. HaitiansCubaPolitics and government. 6. JamaicansCubaPolitics and government. 7. Labor movementCubaHistory. 8. Protest movementsCubaHistory. 9. CubaEconomic conditions. 10. CubaEmigration and immigrationSocial aspects. I. Title.

HD8039.S86C853 2015

331.5'440899607291dc23

2014036417

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

To my wife,

Kelly Y. Hopkins,

and our children,

Kathleen and Thomas

CONTENTS

TABLES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the officials of the Instituto de Historia de Cuba for sponsoring my research. Amparo Hernndez Denis and Belkis Quesada Guerra ensured that I received my researchers visa, letters of introduction, and assistance from a number of Cuban scholars. Oscar Zanettis comments on a paper about Haitians and Jamaicans in the Cuban labor movement that I presented at the Fifth International Conference to commemorate May Day in 2003 were insightful. They became foundational for the fourth chapter. Professor Zanetti also guided me to the newspaper collection housed in the Instituto de Literatura y Lingstica. There, Alina Cuadrado Castellns assistance made my research productive. The director of the Biblioteca Nacional de Jos Mart, Marta Terry, provided me with services of a number of librarians. The care of Eugenio Surez Castro and Zenayda Porra allowed me to continue my research at the Archivo Histrico Provincial de Camagey during the daily scheduled blackouts that were common in 1999 and 2000. The research for this book could not have been completed without Olga Portuondo Ziga, Rebecca Caldern Berroa, and Reynaldo Cruz Ruz. Their kindness and generosity made my research trips to Santiago de Cuba wonderful experiences. The same can be said about the caring and knowledgeable archivists and librarians of the Sir Arthur Lewis Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica; the National Archive of Jamaica in Spanish Town; and the U.S. National Archives at College Park, Maryland. The staff at the Smathers Librarys Manuscripts Division at the University of Florida, Gainesville, especially Carl Van Ness, helped me mine the Rionda-Braga Papers.

I would like to thank Leon Fink, Walter Hixson, Tom OBrien, and Louis A. Prez Jr. for reading multiple drafts of the manuscript. I have tried to address all of their concerns. Tony Martin helped with my analysis of Marcus Garvey in Cuba. Samuel Martnezs constructive observations resulted in revising my approach and arguments. He discerned the multiple historiographies to which this study hopes to contribute. I am also grateful for the support and generosity that John M. Hart has shown since I arrived at the University of Houston. His kindness and understanding were responsible for my research trip to Jamaica. The funding for my research also came from the University of Floridas Summer Research Grant. As the John Moore Distinguished Chair in African American History, Richard J. Blackett also provided me with a substantial grant that allowed me to travel to Cuba several times. I am extremely indebted to him for his unending support and advice since I was his graduate student at Indiana University. Training me as a social historian, he continues to remind me to be critical toward my sources while never dismissing arrogantly the research of other scholars.

I would like to thank the editorial and production staff of LSU Press, especially Rand Dotson, and my editor, Alisa Plant. Their honesty and commitment to direct a fair and unbiased assessment of my manuscript were exemplary. I would also like to thank freelance editor Margaret Dalrymple. Her keen eye and valuable comments during the books copy editing have helped me to convey the significance and excitement of the daily lives of the Caribbean braceros in Cuba. Finally, I would like to thank members of my family, which now only consists of my brothers, Albert and Paul. We are the sons of Albert and Harriet Howard of Gary, Indiana. I am forever grateful to my wife, Kelly Y. Hopkins. She not only read sections of the book, but her technical knowledge was critical in putting it together. She is a terrific mother. I am blessed with her presence and love.

BLACK LABOR, WHITE SUGAR

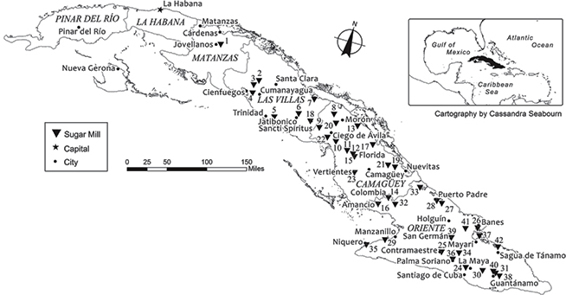

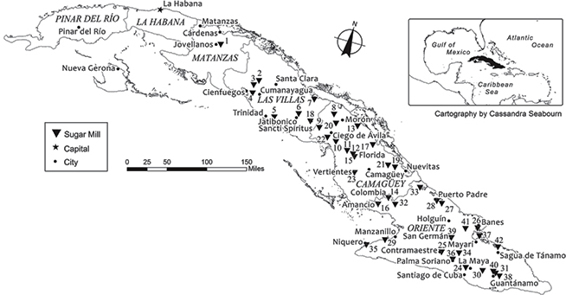

SUGAR MILLS IN CUBA

Matanzas

1. Soledad

Las Villas

2. Caracas

3. Hormiguero

4. Soledad C

5. Trinidad

6. Tuinic

7. Vitoria

Camagey

8. Adelaida

9. Algodones

10. Baragu

11. Camagey

12. Cespedes

13. Cunagua

14. Elia

15. Florida

16. Francisco

17. Jaronu

18. Jatibonico

19. Lugareno

20. Morn

21. Senado

22. Stewart

23. Vertientes

Oriente

24. Algodonal

25. America

26. Boston

27. Chaparra

28. Delicias

29. Dos Amigos

30. Ermita

31. Esperanza

32. Jobabo

33. Manat

34. Miranda

35. Niquero

36. Palma

37. Preston

38. Romelie

39. San German

40. Soledad (G.S. Co.)

41. Tacaj

42. Tanamo

INTRODUCTION

From its beginnings in the colonial era, the cultivation of sugarcane in Cuba engendered immeasurable misery for the predominantly black labor force that cut, loaded, and hauled this tropical commodity. Performing manual field work for a small class of wealthy plantation owners, African cane cutters and haulers, or macheteros and carreteros, suffered under the institution of slavery. By 1910, nearly twenty-five years after their emancipation in 1886, the harsh existence and low social status of the majority of black Cuban sugarcane workers remained unchanged in many ways. After the abolition of slavery, the former slaves and their descendants began to work for wages. During the harvest season, which usually started in late December and lasted through the end of June, they labored daily from sunup to sundown cutting and hauling one to two tons of cane per worker for the sugar mills. Their living quarters continued to consist of poorly constructed, filthy, and overcrowded barracks or

Next page