Table of Contents

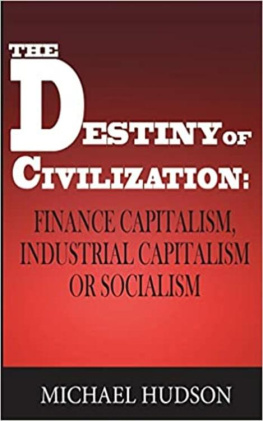

2012 Michael Hudson / ISLET-Verlag

Set in Baskerville

Cover design by Cornelia Wunsch

All rights reserved

www.michael-hudson.com www.islet-verlag.de

Hudson, Michael 1939

Finance capitalism and its discontents. 1.

Interviews and Speeches, 20032012

ISBN 13: 978-3-9814842-1-2

Please submit editorial corrections to

FinanceCapitalism@gmail.com

It is impossible to escape the impression that people commonly use false standards of measurement that they seek power, success and wealth for themselves and admire them in others, and that they underestimate what is of true value in life. We are so constituted that we can gain intense pleasure only from the contrast, and only very little from the condition itself.... The time comes when each of us has to give up as illusions the expectations which, in his youth, he pinned upon his fellow-men, and when he may learn how much difficulty and pain has been added to his life by their ill-will....

What a potent obstacle to civilization aggressiveness must be, if the defence against it can cause as much unhappiness as aggressiveness itself ! Natural ethics, as it is called, has nothing to offer here except the narcissistic satisfaction of being able to think oneself better than others. so long as virtue is not rewarded here on earth, ethics will, I fancy, preach in vain. The element of truth behind all this, which people are so ready to disavow, is that men are not gentle creatures who want to be loved, and who at the most can defend themselves if they are attacked; they are, on the contrary, creatures among whose instinctual endowments is to be reckoned a powerful share of aggressiveness.

Sigmund Freud, Civilization and its Discontents (1930)

Preface

Since 2003 I have been giving a series of interviews to get on record my analysis of debt deflation to explain how the economys debt overhead eats into the production-and-consumption economy. These interviews elaborate the economic analysis I have published in The Bubble and Beyond (2012). The first were with Standard Schaeffer on Counterpunch. Over the ensuing decade I gave more interviews with Bonnie Faulkner on Guns and Butter at KPFK, with Eric Janszen on i-tulip, and most recently with Paul Jay on the RealNews network. Subsequently, I wrote many articles for Counterpunch, Global Research, Naked Capitalism, and the University of Missouri at Kansas City (UMKC) economics blog New Economics Perspectives. Abroad, I have been writing a series of policy articles and historical reviews in the Financial Times, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and numerous foreign-language papers. Most other interviews included in these two volumes are one-time occasions with foreign news media and film documentaries. These all are posted on my website michael-hudson.com, run by Karl Fitzgerald of Prosper Australia.

My usual procedure was to edit the transcripts for clarity, and that is the version that appears here. Lynn Yost helped prepare the book for press. I have worked closely in developing my ideas with Steve Keen (Australia), Dave Kelley (the United States), Dirk Bezemer (the Netherlands), and my colleagues Jeff Sommers (University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee), Randy Wray (UMKC) and Terry Dwyer (Australia).

I could not have produced this work without the support of my wife, Grace Hudson, who has provided an ideal home and working environment and has been a constant source of love and inspiration.

Productivity, compound interest and poverty

Modern Money Theory: Teach-in on February 24, 2012 at Rimini, Italy.

This grassroots event was organized by Italian investigative journalist Paolo Barnard, and attracted 2,181 participants, whose contributions enabled him to bring over my UMKC colleagues Stephanie Kelton, Bill Black and Marshall Auerback, as well as Alan Marquez from France. Bonnie Faulkner supervised and prepared the audiotape for broadcast on her Guns and Butter program on Pacifica Radio on March 9, and Filipe Messina of Media Roots transcribed it.

I have edited my lecture to clarify the distinctions between sovereign money creation and bank credit; commodity-price inflation and asset-price inflation; and between productive and unproductive credit.

Suppose you were alive back in 1945 and were told about all the new technology that would be invented between then and now: the computers and internet, mobile phones and other consumer electronics, faster and cheaper air travel, super trains and even outer space exploration, higher gas mileage on the ground, plastics, medical breakthroughs and science in general. You would have imagined what nearly all futurists expected: that we would be living a life of leisure society by this time. Rising productivity would raise wages and living standards, enabling people to work shorter hours under more relaxed and less pressured workplace conditions.

Why hasnt this occurred in recent years? In light of the enormous productivity gains since the end of World War IIand especially since 1980why isnt everyone rich and enjoying the leisure economy that was promised? If the 99% is not getting the fruits of higher productivity, who is? Where has it gone?

Under Stalinism the surplus went to the state, which used it to increase tangible capital investmentin factories, power production, transportation and other basic industry and infrastructure. But where is it going under todays finance capitalism? Much of it has gone into industry, construction and infrastructure, as it would in any kind of political economy. And much also is consumed in military overhead, in luxury production for the wealthy, and invested abroad. But most of the gains have gone to the financial sector higher loans for real estate, and purchases of stocks and bonds.

Loans need to be repaid, and stocks and bonds receive dividends and interest. For the economy at large, people are working longer just to maintain their living standards, which are being squeezed. Women have entered the labor force in unprecedented numbers over the past half-centuryand of course, this has raised the status of women. Mechanization of housework and other tasks at home has freed them for professional life outside the home. But on balance, the workload has increased.

What also has increased has been debt. When World War II ended, John Maynard Keynes and other economists worried that as societies got richer, people would save more. For them, the problem was to keep market demand high enough to buy all the output that was being produced.

And indeed today, markets are shrinking in many countries. But not because people are saving out of prosperity. The jump in reported saving in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) in recent years has resulted from repaying debts. It is a negation of a negationand hence, a statistical positive.

Paying off a debt is not the same as building up liquid savings in a bank. It reflects something that only a very few economists have worried about over the past century: the prospect of debts rising faster than income, leading to financial crashes that transfer property from debtors to creditors, and indeed polarize society between what the Occupy Wall Street movement calls the 1% and the 99%.

What also was expected universally fifty years agoindeed, until about 1980was that governments would play an increasingly important economic role, not only as forward planners but as direct investors in infrastructure. To Keynesians, government spending served to pump money into the economy, maintaining demand and employment in cyclical downturns. And for hundreds of years, governments have undertaken basic infrastructure spending so that private owners would not use monopoly privileges to charge economic rent.