Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For my parents,

Charlotte Phillips and Oliver Fein,

and for Clara, Jonah,

and Greg

Did mere indifference blister

these panes, eat these walls,

shrivel and scrub these trees

mere indifference?

Adrienne Rich,

The Photograph of the Unmade Bed (1969)

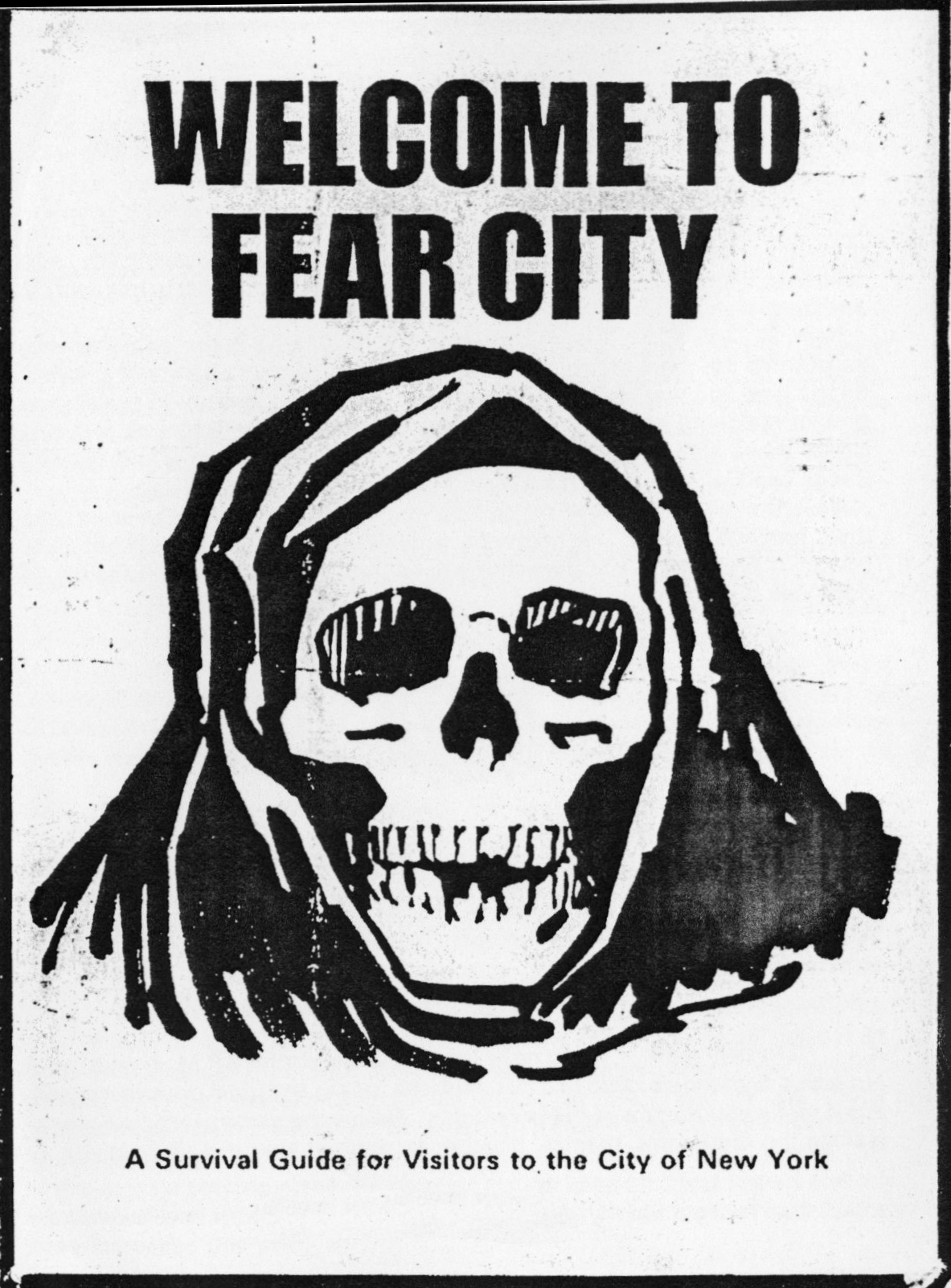

On October 30, 1975, the New York Daily News printed the most famous headline in its history: Ford to City: Drop Dead.

The previous day, President Gerald Ford had delivered a speech at the National Press Club in Washington on the looming bankruptcy of New York City. Once inconceivable, such a collapse fit with the climate of the time. American politics in the autumn of 1975 had taken on the qualities of a grotesque. Saigon had fallen just a few months before Fords speech. The memory of President Nixons resignation in the midst of the Watergate scandal was still fresh. Oil shocks in 1973 had made it clear that the United States could not control supplies of the black gold on which its economy depended, and rapid inflation throughout 1974 and 1975 transformed each paycheck into a game of chance. Across the country, people had been boycotting meat and sugar to protest exorbitant prices. Massive corporate bankruptcies, near-bankruptcies, and financial collapses shook familiar business icons: the Penn Central railroad in 1970, the defense giant Lockheed in 1971, and the Long Islandbased Franklin National Bank, the twentieth largest in the country, in 1974.

The prospect of New York Citys collapse seemed a further terrifying lurch. The leading men at the citys biggest banksincluding First National City Bank (the forerunner of Citibank), Morgan Guaranty, and Chase Manhattanhad spoken out in favor of federal aid for New York. Executives from around the country had traveled to Washington to testify that if the city went under, the fragile national economy might topple as well. Cold Warriors warned that the citys bankruptcy would bolster the Soviet Union. Lawmakers in Washington, Albany, and New York City itself eagerly awaited any hint that Ford might lend his support to a bailout deal. How would it lookwhat would it meanfor New York City, the countrys largest metropolis, the home of Wall Street, the heart of American finance, to wind up in bankruptcy court?

But President Ford and his closest advisersa circle that included his chief of staff, Donald Rumsfeld, and the chairman of his Council of Economic Advisers, Alan Greenspanstrongly opposed federal help for New York. They were convinced that the city had brought its problems on itself through heedless, profligate spending. Bankruptcy was thus a just punishment for its sins, a necessary lesson in how the city should change to move forward. And as far as the national economy was concerned, Ford and his circle believed that the banks, the businessmen, and the city were scaremongering, that the economic impact of the citys financial collapse would easily be containedthat the market had already factored it in. Accordingly, Ford promised to veto the bills that were circulating through Congress to provide emergency aid to New York. Instead, he supported reforms to existing bankruptcy regulations that would make it easier for the city to file. The meaning was clear: New York could go bankrupt, and the federal government would do nothing to help.

For the president, as for much of the nation, New York City stood for urban liberalism, an example of the central role that government might play in addressing problems of poverty, racism, and economic distribution. At the National Press Club, Ford challenged New Yorks network of municipal hospitals and its free public university as lavish, unnecessary extravagances. The federal government should not give a penny in bailout funds that allowed New Yorkers to continue these indulgences, he said. Why should other Americans support advantages in New York that they have not been able to afford for their own communities?

The harsh lesson was intended not only for New York. Ford believed that the United States had to face a new reality: the countryindeed, the worldhad entered an era of slowed economic growth, an age of austerity, in which it was no longer possible for the government to pay for many social services to which the American people had grown accustomed. The citizens basic attitude toward government had to be transformed. Americans needed a revived philosophy of individual initiative centered on fiscal responsibility and limited spending. In the last few minutes of his talk, Ford scolded the nation: If we go on spending more than we have, providing more benefits and more services than we can pay for, then a day of reckoning will come to Washington and the whole country just as it has to New York City. And when that day of reckoning comes, who will bail out the United States of America?

On that note, the president departed for California. He was embarking on a fundraising trip for his 1976 presidential campaign on the home turf of his main rival on the right: the former governor of the state, Ronald Reagan.

Even before Fords speech, there were many in New York who felt that they had been abandoned. A few months earlier, in the spring of 1975, a woman named Lyn Smith wrote a letter to her senator, the liberal Republican Jacob Javits. Smith described the housing conditions in a South Bronx neighborhood near her home. The city, it seemed to her, had stopped making any effort to demolish burned-out buildings, despite their dangers. When a house burns down they dont destroy the frame, they leave it standingyou never know when its going to fall. A little boy I know or knew named Ralfy lives in the South Bronx he was playing in one of the broken down houses and he fell through the floor hes dead now but if that building had been torn down he wouldnt be dead. Smiths toneflat, apathetic, resigned, quietly bearing witness but hardly even launching a protestis perhaps the most haunting aspect of her missive. I dont know why I wrote this letter youll probably never read.

For a woman like Lyn Smith, austerity meant not only budget cuts but a political mood of bleak hopelessness. The fiscal crisis involved discarding a set of social hopes, a vision of what the city could be. For Ford and those around him, the New York City fiscal crisis was a story of the bankruptcyeconomic and moral alikeof liberal politics. It proved that using government to combat social ills would end in collapse. It provided a spectacular repudiation of the Great Society, the War on Poverty, even the New Deal. But for ordinary people, the fiscal crisis meant something different: it marked a change in what it meant to be a New Yorker and a citizen. We are still living with the consequences of this transformation today.

* * *

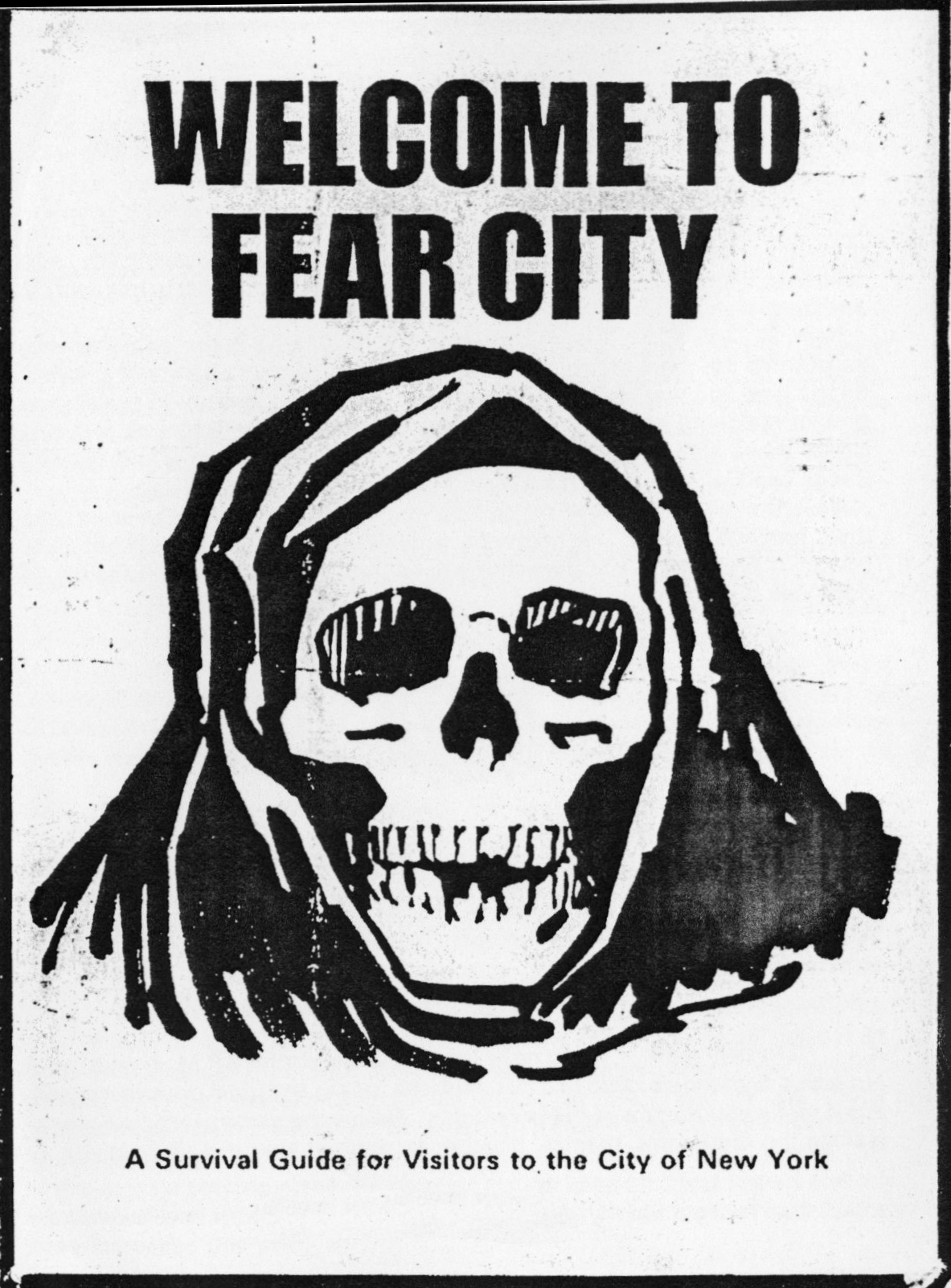

Forty years after the fiscal crisis, the 1970s remain a touchstone of New York City politics, the nightmare era to which no one wants to return. The classic cinema of the 1970s and 1980s memorialized these years of disinvestment and blight in films such as Taxi Driver , The Panic in Needle Park , The Taking of Pelham One Two Three , and Fort Apache, The Bronx , which portrayed New York as a sea of filth and despair, an urban cesspool. The decade is widely remembered as a time of crime, violence, lawlessness, disorder, graffiti-covered subways, inflation, unemployment, and budgets completely out of controlan era of social breakdown, economic malaise, and political collapse.