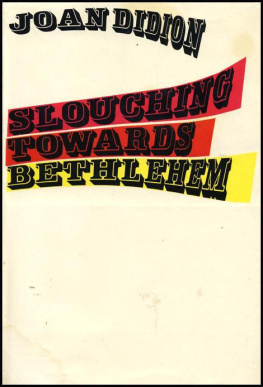

Robert H. Bork

S LOUCHING

TOWARDS

G OMORRAH

M ODERN L IBERALISM AND

A MERICAN D ECLINE

For Mary Ellen, sharer of good days,

comforter on bleak ones

There is good reason why William Butler Yeatss The Second Coming is probably the most quoted poem of our time. The image of a world disintegrating, then to be subjected to a brutal force, speaks to our fears now.

THE SECOND COMING

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

W ILLIAM B UTLER Y EATS

When Yeats wrote that in 1919, he may have foreseen that the twentieth century would experience the blood-dimmed tide, as indeed it has. But he can hardly have had any conception of just how thoroughly things would fall apart as the center failed to hold in the last third of this century. He can hardly have foreseen that passionate intensity, uncoupled from morality, would shred the fabric of Western culture. The rough beast of decadence, a long time in gestation, having reached its maturity in the last three decades, now sends us slouching towards our new home, not Bethlehem but Gomorrah.

Contents

A Word About Structure

Introduction

We Hold These Truths to Be Self-Evident:

The Rage for Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness

We Hold These Truths to Be Self-Evident:

The Passion for Equality

The Supreme Court as an Agent of Modern Liberalism

Killing for Convenience:

Abortion, Assisted Suicide, and Euthanasia

The Politics of Sex:

Radical Feminisms Assault on American Culture

The Wistful Hope for Fraternity

Afterword

P art I of this book begins with two chapters about the Sixties because that decade brought to a climax trends that had long been developing in America and in other nations of the West. It was a politicized decade, one whose activists saw all of culture and life as political. The consequence is that our culture is now politicized. It worked the other way as well: our politics is increasingly (we need such a word) culturized. We have a new and extremely divisive politics of personal identity. We have invented a range of new or newly savage political-cultural battlegrounds. Democrats and Republicans have begun to line up on opposing sides of the war in the culture.

Because my thesis is that these developments have been coming on for a long time and may be inherent in Western civilization, Part I continues with two chapters that examine the themes of liberty and equality, which were celebrated in the Declaration of Independence and are dominant in our culture today. These ideals have been pressed much too far and account for the cultural devastation wrought by modern liberalism. Chapters 5 and 6 discuss the forces that advance the agenda of modern liberalism: the intellectual class and that classs enforcement arm, the judiciary, headed by the Supreme Court of the United States.

Part II, consisting of chapters 7 through 15, examines the particular institutions and areas of cultural warfare that result from the twin thrusts of modern liberalism: radical individualism and radical egalitarianism. This part of the book takes up the collapse of popular culture; the case for censorship; crime, illegitimacy, and welfare; abortion and euthanasia; the politics of sex (radical feminism); the dilemmas of race; the decline of intellect; the trouble in religion; and the fragmentation of our society into warring groups.

Part III consists of two chapters examining the prospects for the survival of democratic government and the question of whether America can reverse its decline and avoid becoming Gomorrah.

O ne morning on my way to teach a class at the Yale law school, I found on the sidewalk outside the building heaps of smoldering books that had been burned in the law library. They were a small symbol of what was happening on campuses across the nation: violence, destruction of property, mindless hatred of law, authority, and tradition. I stood there, uncomprehending, as a photograph in the next days New York Times clearly showed. What did they want, these students? What conceivable goals led them to this and to the general havoc they were wreaking on the university? Living in the Sixties, my faculty colleagues and I had no understanding of what it was about, where it came from, or how long the misery would last. It was only much later that a degree of understanding came.

To understand our current plight, we must look back to the tumults of those years, which brought to a crescendo developments in the Fifties and before that most of us had overlooked or misunderstood. We noticed (who could help but notice?) Elvis Presley, rock music, James Dean, the radical sociologist C. Wright Mills, Jack Kerouac and the Beats. We did not understand, however, that far from being isolated curiosities, these were harbingers of a new culture that would shortly burst upon us and sweep us into a different country.

The Fifties were the years of Eisenhowers presidency. Our domestic world seemed normal and, for the most part, almost placid. The signs were misleading. Politics is a lagging indicator.

Culture eventually makes politics. The cultural seepages of the Fifties strengthened and became a torrent that swept through the nation in the Sixties, only to seem to die away in the Seventies. The election of Ronald Reagan in 1980 and the defeat of several of the most liberal senators seemed a reaffirmation of traditional values and proof that the Sixties were dead. They were not. The spirit of the Sixties revived in the Eighties and brought us at last to Bill and Hillary Clinton, the very personifications of the Sixties generation arrived at early middle age with its ideological baggage intact.

This is a book about American decline. Since American culture is a variant of the cultures of all Western industrialized democracies, it may even, inadvertently, be a book about Western decline. In the United States, at least, that decline and the mounting resistance to it have produced what we now call a culture war. It is impossible to say what the outcome will be, but for the moment our trajectory continues downward. This is not to deny that much in our culture remains healthy, that many families are intact and continue to raise children with strong moral values. American culture is complex and resilient. But it is also not to be denied that there are aspects of almost every branch of our culture that are worse than ever before and that the rot is spreading.

Culture, as used here, refers to all human behavior and institutions, including popular entertainment, art, religion, education, scholarship, economic activity, science, technology, law, and morality. Of that list, only science, technology, and the economy may be said to be healthy today, and it is problematical how long that will last. Improbable as it may seem, science and technology themselves are increasingly under attack, and it seems highly unlikely that a vigorous economy can be sustained in an enfeebled, hedonistic culture, particularly when that culture distorts incentives by increasingly rejecting personal achievement as the criterion for the distribution of rewards.