For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance; but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.

(St Matthew 25:29)

The Gospel of St Matthew tells the story of a man who goes abroad and leaves his fortune to his servants. He gives one five talents of silver, he gives a second two talents and gives a third one talent. The first two servants engage in trade and double their silver. The third servant, however, buries his talent. When the master returns, he praises the first two for their faithfulness: Well done, thou good and faithful servant: thou hast been faithful over a few things. He accuses the third of being an unprofitable, wicked and slothful servant, and gives the order: take therefore the talent from him, and give it unto him which hath ten talents.

For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance; but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath. (St Matthew 25: 2829)

The Matthew Effect is known not only in the field of sociology. In the vernacular it is also known as Der Teufel scheit immer auf den grten Haufen (money makes money, literally: the devil always takes a shit on the biggest pile); the rich get richer; success leads to success; it always rains where its already wet. Nobody has ever got rich through hard work, says another maxim, and an English saying points the way to the alternative: money makes money.

That which one can regard as either a suspicion or knowledge based upon experience was proved by the economist Thomas Piketty. At least, that is what he intended to do. In a huge book with vast quantities of statistical material which, thanks to the expansion of the financial bureaucracy as a result of the bourgeois revolutions, deals primarily with the last 200 years he depicts how, when and why the distribution of wealth has become, and is becoming, increasingly unequal.

When Pikettys book Capital in the Twenty-First Century was published in France in the summer of 2013, it had a friendly reception. However, it did not get very much attention. The hype first began with the American edition in March 2014, when Paul Krugman, winner of the Nobel Prize in economics in 2008, celebrated Pikettys work as the most important book of the year and possibly of the decade. It was a book that will change both the way we think about society and the way we do economics. Martin Wolf, columnist for the British Financial Times, declared it to be an extraordinarily important book that nobody should ignore. The German economist and so-called Wirtschaftsweise, or economic sage Peter Bofinger praised the book and attested that Piketty had succeeded in finally putting the urgently necessary discussion about the future of the market economy at the centre of public attention.

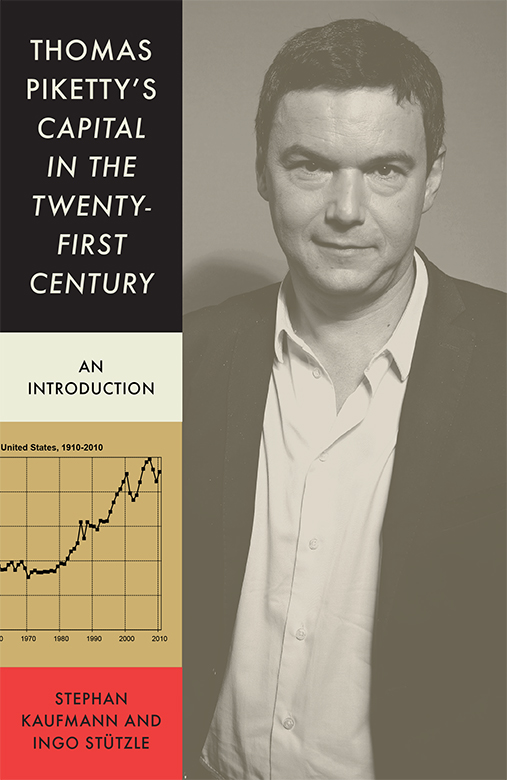

An economist as rock star: Piketty as cover boy

For a long time, the book occupied the number one spot of the Amazon bestseller list, the first printing sold out quickly, and it is supposed to have made the author a millionaire. Pikettys first reading tour through the United States resembled that of a rock star. He presented his findings to the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the senior staff of US President Obama. Large newspapers in Europe and America devoted much space to the book and vied for interviews in which Piketty could elucidate and defend his theses. The only thing missing from the rock star comparison were tour dates on his website.

The hype is remarkable, since alongside the praise it was maintained that Piketty advanced a most simplistic thesis and provided evidence in his book for that which the people have known for a long time. And not just the people; numerous empirical investigations in the past had demonstrated the divergence between rich and poor in the industrialized countries. So if Piketty was merely writing what was already well known and proven, what was all the excitement about? In order to explain that, one first has to consider the context in which the book was published. And then, one has to consider the content of the book.

The Prelude: Redistribution,

Inequality and Debt Crisis

The great attention that Piketty received can be explained for one thing by the contemporary economic situation and its pre-history. In the 1980s there began what was later called the neoliberal age. Among other things, it involved the redistribution of the tax burden from capital income to wage income and consumption. The concept behind this was lifting the burden from capital in order to promote investments and thus economic growth.

Between states this became noticeable as a competition for investment, in which every country lowered its taxes on capital and business in order to attract capital. This strategy of courting capital was regarded as without alternative, since businesses and investors would otherwise leave the country:

Whoever keeps taxes high here shouldnt wonder if businesses move to countries that are more advantageous tax-wise. What use are nice theories if businesses close or move away? We cannot allow that under any circumstances. Germany must court enterprise capital, since only that guarantees innovations, growth, and jobs.

Here are some examples of the consequences of this competition between states in Europe:

Tax competition. Between 1997 and 2007, the average corporate tax rate in the old EU countries fell from 38 to 29 per cent, in the new EU entry countries from 32 to 19 per

At the same time the top personal income tax rate in the EU-15 (UK) went down from an average of 67 (60) per cent in 1980 to 48 (40) per cent in 2006. For the EU-25 it was only 42 per cent. US President Reagan lowered the top tax rate in 1982, initially from 70 per cent to 50 per cent, and then to 28 per cent.

Transition to dual income taxation. Profits on interest and from dividends are increasingly subject to a flat tax and no longer to an individual, progressive tax rate. That means that the higher the income, the higher therefore the income tax rate, the more the taxpayer profits from the flat tax upon income from interest.