Contents

BIBEK DEBROY

SANJAY CHADHA

VIDYA KRISHNAMURTHI

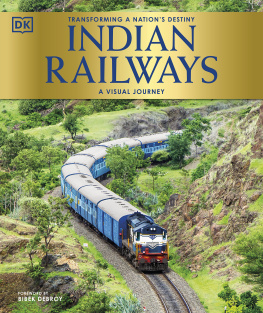

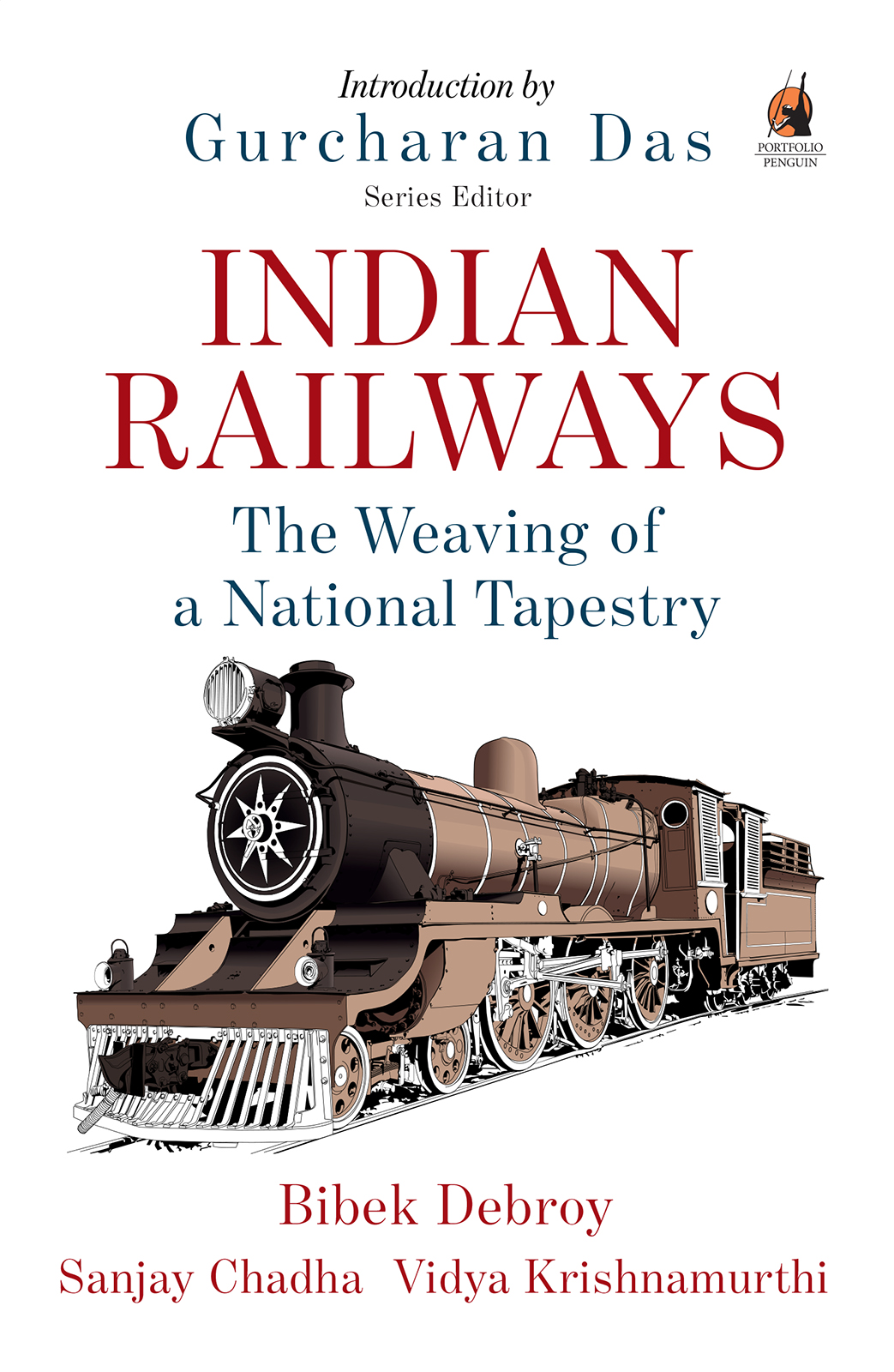

INDIAN RAILWAYS

The Story of Indian Business

The Weaving of a National Tapestry

With an introduction by Gurcharan Das

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

PORTFOLIO

INDIAN RAILWAYS

BIBEK DEBROY is an economist and is currently a member of Niti Aayog. He was the chairman of a committee set up by the ministry of railways to recommend desired reforms. In the past, he has worked in academia, business chambers and the government. He is the author of several books, papers and popular articles, and writes columns for newspapers and magazines.

SANJAY CHADHA is presently working as joint secretary in the department of commerce where he handles international trade with Northeast Asia. He is also the nodal officer for trade infrastructure and mainstreaming of the Indian states in international trade. He has worked in various capacities for over two decades for the Indian Railways. He done an MBA from the Faculty of Management Studies, University of Delhi and has a bachelors degree in mechanical engineering and production technology from the Engineering Council, UK. He has published widely in domestic and international journals.

VIDYA KRISHNAMURTHI is a researcher with Indicus Foundation, New Delhi, with an interest and experience in ancient Indian history and cultural history of the premodern period. Her current project focuses on the Indus Valley Civilization and the historical linkages between India and South East Asia. Previously, she worked at Niti Aayog as a Young Professional. She holds a masters in East Asian studies from the Faculty of Social Sciences and a bachelors in history from University of Delhi. She also writes short stories for children.

GURCHARAN DAS is a world-renowned author, commentator and public intellectual. His bestselling books include India Unbound, The Difficulty of Being Good and India Grows at Night. His other literary works consist of a novel, A Fine Family, a book of essays, The Elephant Paradigm, and an anthology, Three Plays. A graduate of Harvard University, Das was CEO of Procter & Gamble, India, before he took early retirement to become a full-time writer. He lives in Delhi.

THE STORY OF INDIAN BUSINESS

Series Editor: Gurcharan Das

Arthashastra: The Science of Wealth by Thomas R. Trautmann

The World of the Tamil Merchant: Pioneers of International Trade by Kanakalatha Mukund

The Mouse Merchant: Money in Ancient India by Arshia Sattar

The East India Company: The Worlds Most Powerful Corporation by Tirthankar Roy

Caravans: Punjabi Khatri Merchants on the Silk Road by Scott C. Levi

Globalization before Its Time: The Gujarati Merchants from Kachchh by Chhaya Goswami (edited by Jaithirth Rao)

Three Merchants of Bombay: Business Pioneers of the Nineteenth Century by Lakshmi Subramanian

The Marwaris: From Jagat Seth to the Birlas by Thomas A. Timberg

Goras and Desis: Managing Agencies and the Making of Corporate India by Omkar Goswami

Indian Railways: Weaving of a National Tapestry by Bibek Debroy, Sanjay Chadha and Vidya Krishnamurthi

Introduction

My heart is warm with the friends I make,

And better friends Ill not be knowing

Yet there isnt a train I wouldnt take,

No matter where its going.

Edna St Vincent Millay

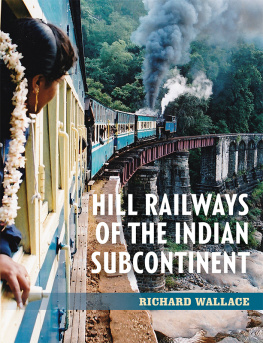

Every Indian seems to have at least one impossibly romantic railway memory. Mine is of a journey from Kalka to Shimla when I was five. From the window of our train, my family and I feasted, for the first time, on the snow-tipped crests of the Himalayas. With each bend of the winding track, we passed green slope after green slope, their tiers of neatly cultivated terraces looking like gardens hanging in the air. Belts of pine, fir and deodar punctuated the terraces, and masses of rhododendrons clothed the slopes. Below, towards the south, the Ambala plains seemed to recede as the Sabathu and Kasauli hills appeared in the foreground. To the north rose the confused Himalayan mountain chains, range after snowy range.

The train stopped at Barog, where we ate the most delicious puri-alu. The station was named after a railway engineer named Barog, who had built the infamous tunnel number thirty-three, as the authors of this volume inform us. He started to dig the tunnel from opposite ends of the mountain, hoping that the digging parties would meet in the centre. But they did not, and Barog shot himself and his dog, unable to bear the ignominy. The railway company then hired a certain Baba Bhalku, who apparently had the ability to tap on the mountain wall with a stick and tell from the sound where it could be dug. Bhalku became a legend and helped to build all the tunnels to Shimla.

One of Bhalkus last tunnels was at Shogi, where we had our first wondrous vision of Shimla. From afar, it looked like a mythical, green-carpeted garden dotted with red-roofed Swiss chalets. My excitement mounted as we neared. We passed Jutogh, crossed Summer Hill, turned into tunnel number 103, and finally reached Shimlas Victorian railway station. By then I had fallen in love with the railway, and ever since, whenever I have heard a train whistle, I have wished, like Edna St Vincent Millay, that I were on that train. But these longings are dying rapidly in an age of railway mediocrity that has crept insidiously upon India during the past two generations.

Indian Railways: The Weaving of a National Tapestry by Bibek Debroy, Sanjay Chadha and Vidya Krishnamurthi is a charming attempt to recapture the power and poetry of the building of, and travel on, the railways in India, from the mid-nineteenth century to Independence. It is hard to imagine that the men who built the railways belonged to a profession of heroes, but this is exactly what our authors show in the lives of engineers like Rowland Stephenson, John Chapman and Arthur Cotton in this lively tenth volume of Penguins The Story of Indian Business. Stephenson dreamt of connecting London and Calcutta by rail, which would reduce the journey between England and its Indian empire to ten days; he also wanted to link Calcutta with Peking and Hong Kong.

Arthur Cotton was a hero to my engineer father. When I was a child, I remember listening to my father speak enthusiastically about Cottons idea of connecting our subcontinent with inland waterways as an alternative to the railways. To connect Indias rivers and form a robust system of inland water transportation was not a hare-brained ideait was seriously debated in the British parliament in the nineteenth century. The railways won in the end, in part because of a powerful lobby. Ever since, I have nostalgically wondered whether, if India had also invested in inland waterways for transport, we might not have got the side benefit of irrigating our arid lands and making our agriculture less vulnerable while also providing cheap transport to the people. The authors of this book give a fascinating account of this controversy of railways-vs-inland waterways in a dialogue between the anonymous P and C.