The INS had a long tradition of denying that it ever had a humanitarian program to benefit noncitizens. In official bar association liaison committee meetings with the New York district director of the INS that I attended before 1972, District Director Peter Esperdy, in response to a direct question, denied the existence of a nonpriority program or any other policy by which the INS might defer or decline the removal of eligible noncitizens. Although district directors had been routinely forwarding meritorious hardship cases to regional commissioners, this beneficial program was practiced sub rosa and was never publicly discussed or acknowledged.

In August 1971, John Lennon and Yoko Ono arrived in the United States on visitor visas. They retained me in January 1972 to assist them with their immigration problem. Yoko had an eight-year-old daughter, Kyoko, whose father, Yokos former American husband Tony Cox, had absconded with her several years earlier and the child was nowhere to be found. John and Yoko had just secured a court order for the childs temporary custody in the U.S. district court in Saint Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, where Yoko and Tony had divorced, and the court granted Kyokos temporary custody to her and John. Tony Cox then filed a new custody proceeding in Texas, where Yoko and John also appeared and secured a temporary custody order from that court as well. But once again, Tony Cox absconded with the child and needed to be located.

I approached the INS district director, Sol Marks, and requested an extension of stay to permit the Lennons to find Kyoko and secure her custody, which I felt was the strongest reason for an extension of stay I had ever heard. Upon checking with the Office of the INS Commissioner, Marks granted only a one-month extension and issued a warning that my clients had better leave.

Unknown to us at the time, the commissioner had received a letter from Senator Strom Thurmond representing the Internal Security Subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee, advising that John Lennons presence in the United States could be detrimental to President Richard Nixons reelection plans. Lennon, who had an immense impact on young people, had been discouraging young Americans from serving in Vietnam, and the upcoming November election was to be the first time in U.S. history that eighteen-to-twenty-year-olds would be permitted to vote. This information was shared with District Director Marks and soon resulted in the institution of harsh deportation proceedings against John and Yoko as overstayed visitors. The INS assumed that Lennon would have no choice but to leave or be deported, since his old British marijuana conviction would leave him no other choice.

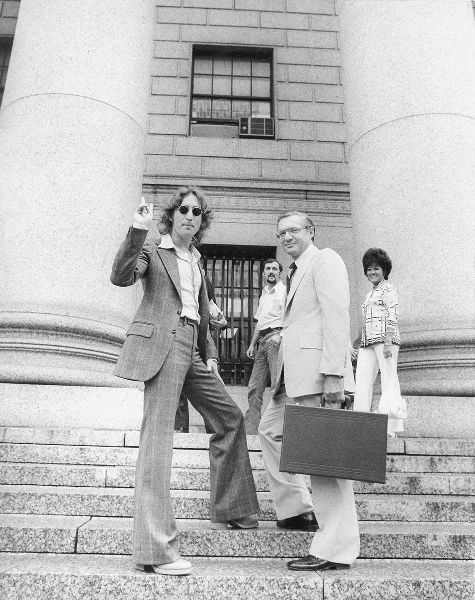

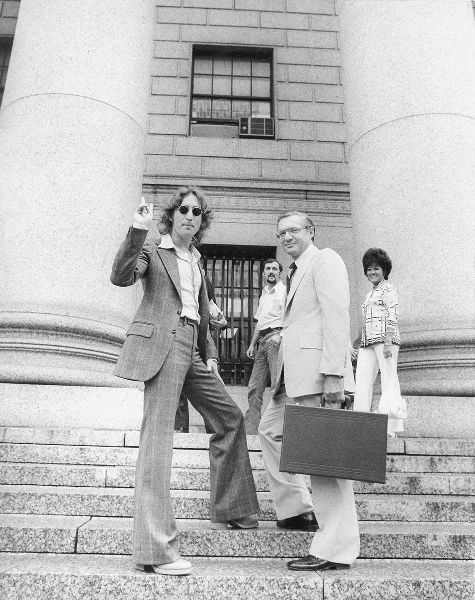

Former Beatle John Lennon, left, with his attorney Leon Wildes, right. Photo courtesy of Leon Wildes.

During the deportation proceedings and thereafter, District Director Marks was continuously interviewed in the media. As the official voice of the INS, he continuously claimed that I am an enforcement officer and I have an obligation to remove every illegal alien. John Lennon is not being treated differently from any other illegal alien.

The case lasted five years. Among the steps that I took on Lennons behalf was the filing of a federal action under the Freedom of Information Act. I demanded documentation of the INS nonpriority program, later known as deferred action. Eventually, I secured a copy of the provision of law, in an unpublished INS Operation Instruction, as well as copies of 1,843 approved nonpriority cases. I published the provision and analyzed the cases in a series of articles on deferred action published in the San Diego Law Review. With Johns encouragement, I was anxious to publicize my discovery and analyze the basis upon which the INS had exercised its prosecutorial discretion in past years. In addition, I learned that no nonpriority request had been made in the Lennon case itself. I felt that John and Yokos plight merited prosecutorial discretion.

The New York U.S. attorney wrote to Federal Judge Owen and suggested that it was appropriate for the INS to consider an application for nonpriority classification for John Lennon. He also instructed that no INS officer previously involved with the case be allowed to participate. I drafted the nonpriority request, which was filed and processed through the Office of the Commissioner of Immigration, using the same procedure as the nearly two thousand similar cases. My application was granted, and thus John Lennon was granted nonpriority status. Two weeks later, he was granted lawful permanent resident status by an order of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, notwithstanding his marijuana conviction, in 1976.

Imagine my gratification upon meeting Shoba Sivaprasad Wadhia, a talented young lawyer and professor who had taken up my favorite cause where I had left off. I was pleased as well when I later learned that she was producing a book essential to this vital area of developing law and policy. Her book capably examines prosecutorial discretion as it applies in the immigration context, its relation to prosecutorial discretion in the criminal process, the precise details of deferred action, how it has been applied by the Obama administration, particularly in respect to its expanded use to assist young people, and the technical effect of judicial review and the Administrative Procedure Act in this area. She also outlines her efforts in securing and publicizing prosecutorial discretion programs and her recommendations for improving prosecutorial discretion in the immigration system. I am proud to say that I consider this work to be a major contribution to this vital area of developing law.