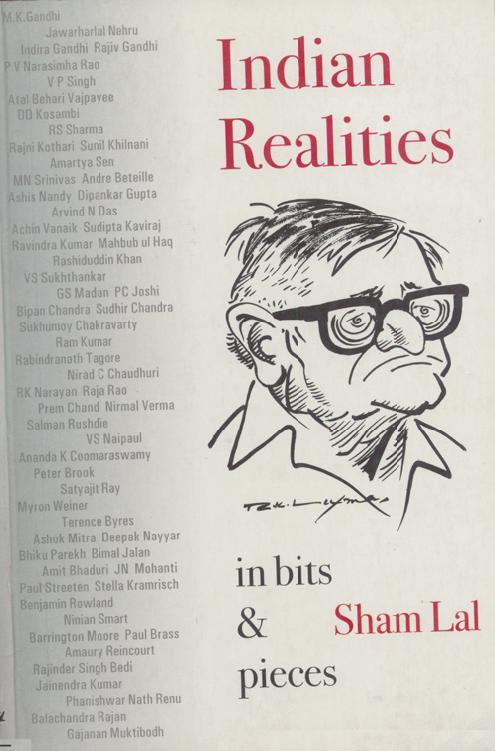

Copyright Sham Lal 2003

First Published 2003

First in Rupa Paperback 2007

Published by

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

Sales Centres:

Allahabad Bangalore Chandigarh

Chennai Hyderabad Jaipur Kathmandu

Kolkata Mumbai Pune

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Typeset in 11 pts. Aldine by

Nikita Overseas Pvt Ltd

1410 Chiranjiv Tower,

43 Nehru Place

New Delhi 110 019

Printed in India by

Rekha Printers Pvt. Ltd.

A-102/1 Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-II

New Delhi-110 020

Contents

Introduction

T he word 'realities' in the title of this collection of essays, most of them review articles, each bearing on some aspect of Indian history, politics, economy, art or literature, is highly suspect at a time when the virtual and the imaginary often pass as real. This is why I qualify it with the phrase 'in bits and pieces' to stress the fragmentary character of the book and rebut the notion of a vantage point from where one can view or assess the whole national scene in so large and diverse a society as India's. Even where I make broad generalisations, I do so with an uneasy awareness of their provisional and open-ended nature in a situation where the frenzy of the new forces for change, both internal and external, defies the discipline of any grand theory.

Just as there has been of late a proliferation of elite, subaltern, caste and ethnic histories, depending on different perceptions of the past, there have been many reconstructions of present-day life, political, economic, social or cultural, reflecting the aggrandised identities of religious, regional, tribal and other groups. India's post-colonial history has been a story of frustrated hopes, sluggish economic growth, political fragmentation, increased violence in public life and a growing overload of demands on the system which the state is unable to process or mediate because of the steady erosion of its steering capacity.

Unfortunately for the country, the years of its independence saw a conjunction of four developments, making management of change extremely difficult. The first of these was a population explosion which prevented a rather modest rate of economic growth from making a significant dent in poverty. The second was a frantic pace of technological change which made the country lag far behind many others in both productivity and prosperity levels. The third was the logic of the democratisation process set in motion by adult franchise. The splintered political life has fractured electoral verdicts in recent years and produced hung parliaments resulting in ruling coalition of disparate groups. All this has made for political instability, further deepening the crisis of governance.

The last but not the least malevolent of the four developments is the ongoing globalisation process, which is putting new power structures, based on monopolies of investment capital and new technologies, in place. The terms of trade are rigged against the poor and they can do little about it. Official hype in India may hail the USA as the country's natural ally, and recent events have certainly brought the two somewhat closer to each other. Even so, there are all too frequent reminders that America's priorities as the only superpower are quite different from those of India which has taken too long to imbibe the all too obvious fact that the limits of a nation's room for manoeuvre in foreign policy are the limits of its military and economic clout.

The encounter between modernity and tradition here over the last 50 years has not been too happy. It is not just a case of misunderstandings arising from their different approaches to the right kind of relationship the individual ought to have with the cosmos, with nature, with the community to which he belongs and with his own self. It is primarily a problem bound up with wide disparities of power. Modernity disrupts and disorients traditional societies which have their revenge by making a hash of the values that come with it. The result is an odd assortment of cultural hybrids or grotesques.

The various local traditions here were friendly to the ecological environment. Modernity wants to exploit nature for human ends. The old societies, despite widespread deprivation, promoted a culture of contentment by setting limits to human needs. Modernity becomes an unwitting cause of endemic discontent by creating one new need after another without being able to satisfy the basic necessities of hundreds of millions of people. It does not see the cruel irony of the kind of society it produces. The most industrially advanced countries have eased the burden of daily toil and yet more people complain of job stress than ever before. They have access to means of instant communication but little to communicate by way of meaning, and place a high value on self-expression without a self to express. Modernity is busy fouling its own nest and the aim is not so much to pay heed to existential problems as to dominate both nature and weaker societies.

The paradox is that, despite the despoiling of nature, warping of human relations and putting in place a new international pecking order, it has lost none of its lure for those it wants to turn into client states of the dominant military and economic power. Thanks to the political dislocations, cultural disorientations and new social and ethnic conflicts fostered by the modernisation process, the world has to put up with far more violence, more widespread psychic disorders and a more acute sense of loss of meaning.

This raises many awkward questions for the modernising elite here, particularly when the market theology is commodifying not only all consumer and capital goods but all ideas, philosophies, arts and other works of the human mind. How can the modernisation process be made less disruptive in India in these circumstances? How can the state here preserve its freedom of action and refuse to yield too much ground to the new hegemonic power? How can the country reduce the regional and personal income disparities that have become a threat to national integrity and internal peace? How can it prevent the pathologies of modernity from undermining the process of development and infecting both political and economic cultures with more virulent viruses of amorality and cynicism?

Answers to these questions demand something more than a change in laws and bureaucratic procedures. They call for a commitment by those in public life to more exacting norms of integrity and general welfare. Politics today mostly draws persons with a yen for powers of patronage and insensitive to the obscenity of the stark contrasts between the newly rich and those without work and often without enough to eat. Small hi-tech enclaves flourish amidst large huddles of sweatshops. Posh colonies co-exist merrily with stinking shanties. Schools without any teaching aids and often without even clean drinking water, meant for the majority of children, turn out millions of young persons fated to relapse into illiteracy while private schools with proper teaching and extra-curricular facilities cost as much by way of fees as a poor family earns in a month.