Contents

Landmarks

Jack Lawrence Luzkow

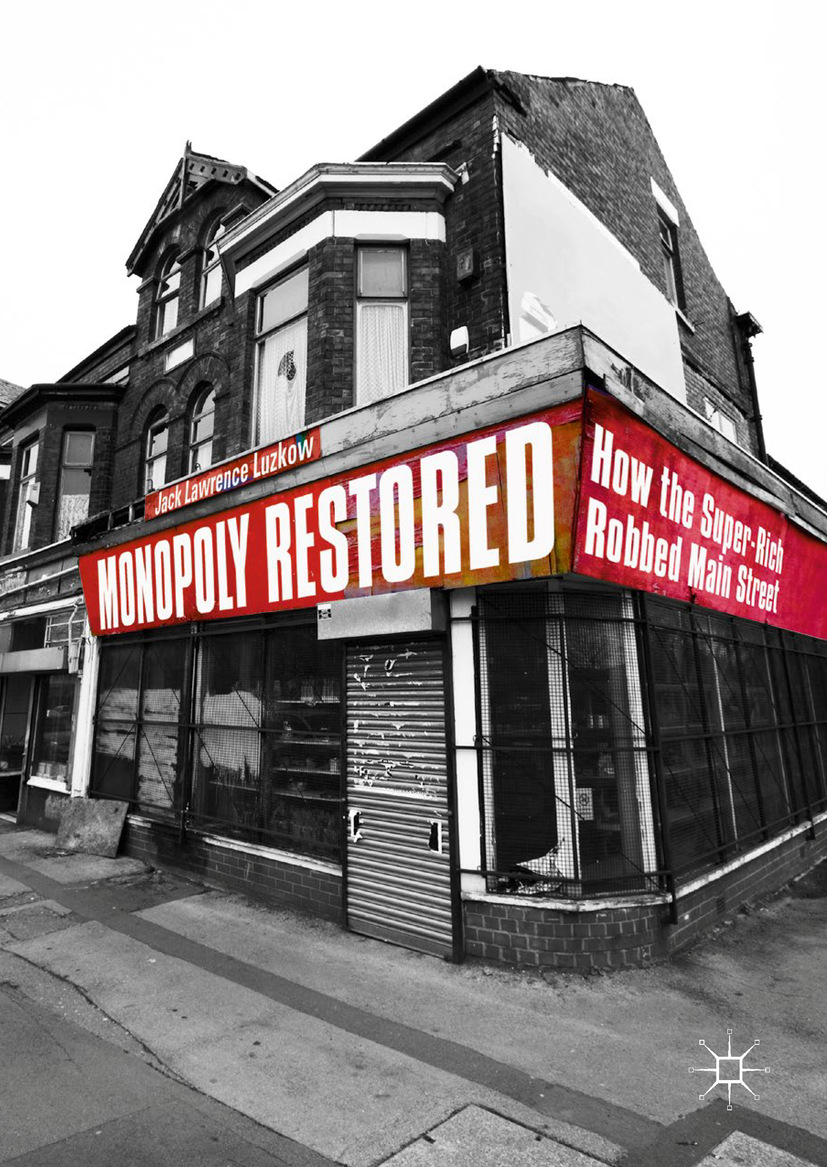

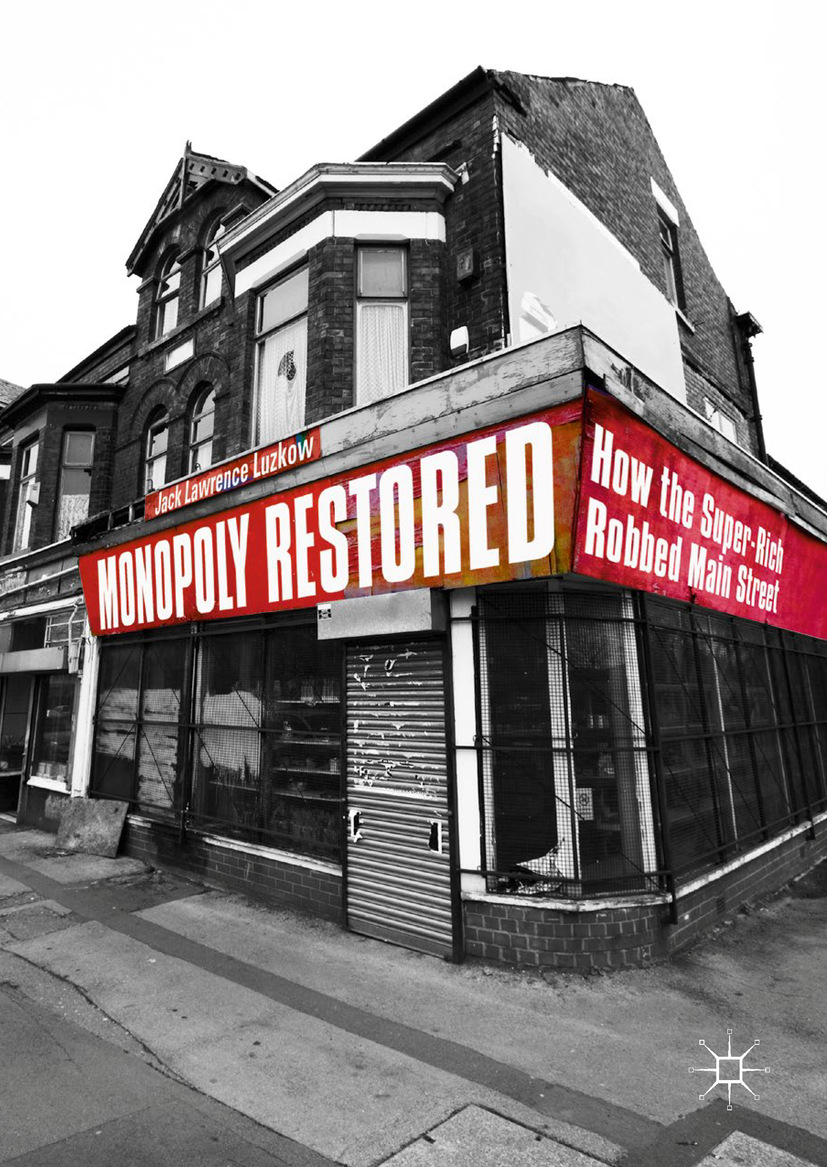

Monopoly Restored How the Super-Rich Robbed Main Street

Jack Lawrence Luzkow

Fontbonne University, St. Louis, MO, USA

ISBN 978-3-319-93993-3 e-ISBN 978-3-319-93994-0

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93994-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018946179

The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer International Publishing AG, part of Springer Nature 2018

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Cover image: onfilm, istock/Getty Images Plus

Cover design by Akihiro Nakayama

This Palgrave Macmillan imprint is published by the registered company Springer International Publishing AG part of Springer Nature

The registered company address is: Gewerbestrasse 11, 6330 Cham, Switzerland

For Roberto Giammanco, who taught me to see

The Author(s) 2018

Jack Lawrence Luzkow Monopoly Restored https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93994-0_1

1. Introduction

Jack Lawrence Luzkow

(1)

Fontbonne University, St. Louis, MO, USA

Jack Lawrence Luzkow

Email:

Like the majority of Americans, I did not expect Donald J. Trump to be elected president of the USA. No more than many in Britain expected Brexit to win the approval of British voters. Yet, like many others, I could also see the possibility that both Brexit and Trump would be triumphant. It did not take great insight or foresight to see that the press, the media generally, many politicians, and virtually all major political parties on both sides of the Atlantic were missing massive populist revolts that seemed all but invisible to the parade of public commentators.

Even while there was much talk of economic recovery, the rate of poverty in the USA reached 17% in 2016. A percentage roughly double that had been in poverty at some point between 2010 and 2013: the same was true for the UK. The official rate of unemployment may have been reduced to below 5% in the US and almost as low in the UK by 2017, but these calculations were badly flawed. If part-time employment was not counted as being in-work, if people were not counted as working when they were nominally self-employed, then the rate of official unemployment doubled or worse, in the USA and the UK.

In both countries, wages have remained stagnant for the middle classes and have been so for decades. The working classes practically have become invisible in both countriesat least prior to Brexit and the election of Donald Trump as both nations have abandoned manufacturing, arguing that blue-collar industrial jobs were best done in low-wage countries. The irony is that for many, the UK and the USA have become low-wage countries themselves. But it is worse than that. The middle classes on both sides of the Atlantic have been struggling for decades, facing stagnating incomes at best, or long-term unemployment as many so-called middle-class jobs have either evaporated or been exported abroad.

Conservatives on both sides of the Atlantic point out that this was the inevitable result of globalization and automation. Some say it is because of poor decisions made by the less successful, the impoverished and the uneducated: they failed to get the right skills, or education, their productivity was low, and American and British workers were not competitive. Moreover, Republicans and Tories have argued for decades that labor unions are greedy, practice class conflict, and advocate unreasonable wage hikes that raise prices, lead to inflation, and make products more and more unaffordable. Inevitably, as jobs have disappeared, as wages have stagnated, as millions have failed to participate in so-called recovery, as unions have been eviscerated, and as political parties have failed to respond to the suffering that they have not acknowledged, or simply could not see, the mass parties of the past began to fragment, unsure of who or where their constituencies were.

Constituencies themselves have become more complex, divided by identity politics, regional attachments, social and class divisions, and polarized further by immigration and population movements as both the USA and the UK became less Western, less Christian, and less white. Identity politics have proved especially nettlesome, as gender identity has become more amorphous and ill-defined, and as marriage has become something other than between a man and a woman, challenging traditional white populations already threatened as their neighbors and countries became less Christian and less white. And as whites, particularly the traditional bread-winning male populations, have become more threatened, as their jobs have been eviscerated or exported, as more and more have been displaced, and as they have had to compete with low-wage workers in far-flung countries, Conservatives everywhere have successfully argued that their problems were the result of Big Government: too many taxes, too much support of illegal immigrants, too much protection of trees and certain animal species, too little concern for workers who had nothing to look forward too.

In the midst of these problems, liberals seemed unable to articulate a vision for the future. They became too cozy with Wall Street in the USA and the City in Britain. They became part of the establishment, more and more distant and increasingly unaware of or insensitive toward the suffering of their traditional constituents. On both sides of the Atlantic, the major parties moved to the right, Democrats embracing compromise with Republicans as a way to acquire power, and Tony Blair and Labor doing the same in Britain to accommodate the Tories . For decades, in both the USA and the UK, major political parties accepted the viewpoints of Big Business: keep taxes low, government regulation at a minimum, low or no tariffs at the border, minimal if any carbon tax, weak unions, and strong currencies.

What progressive parties on both sides of the Atlantic failed to do was to adequately acknowledge or grasp the multiple crises at hand. We have been floundering in the USA and the UK now for several decades, following the end of history, or at the least the End of Communism as a serious historical force, as to what exactly our alternatives should be in the non-Communist West. It is time now to admit and to fully acknowledge that Europe and the USA have been facing dual crises of capitalism and liberal democracy, and for Europe a continuing crisis of unity. More than crises, the West now faces a historical caesura marking the end of liberalism as we have known it, and the beginning of a new era of authoritarianism that is a reminder of things past, if not a return of history. German historian Philipp Ther, though addressing the failures of the Western model of liberal democracy and economic liberalism in Central and Eastern Europe, has inadvertently put the current crisis in the West in historical perspective. Ther has argued that a neoliberal train set in motion by Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in the USA began to cross into Europe in 1989. He states the problem with clarity: