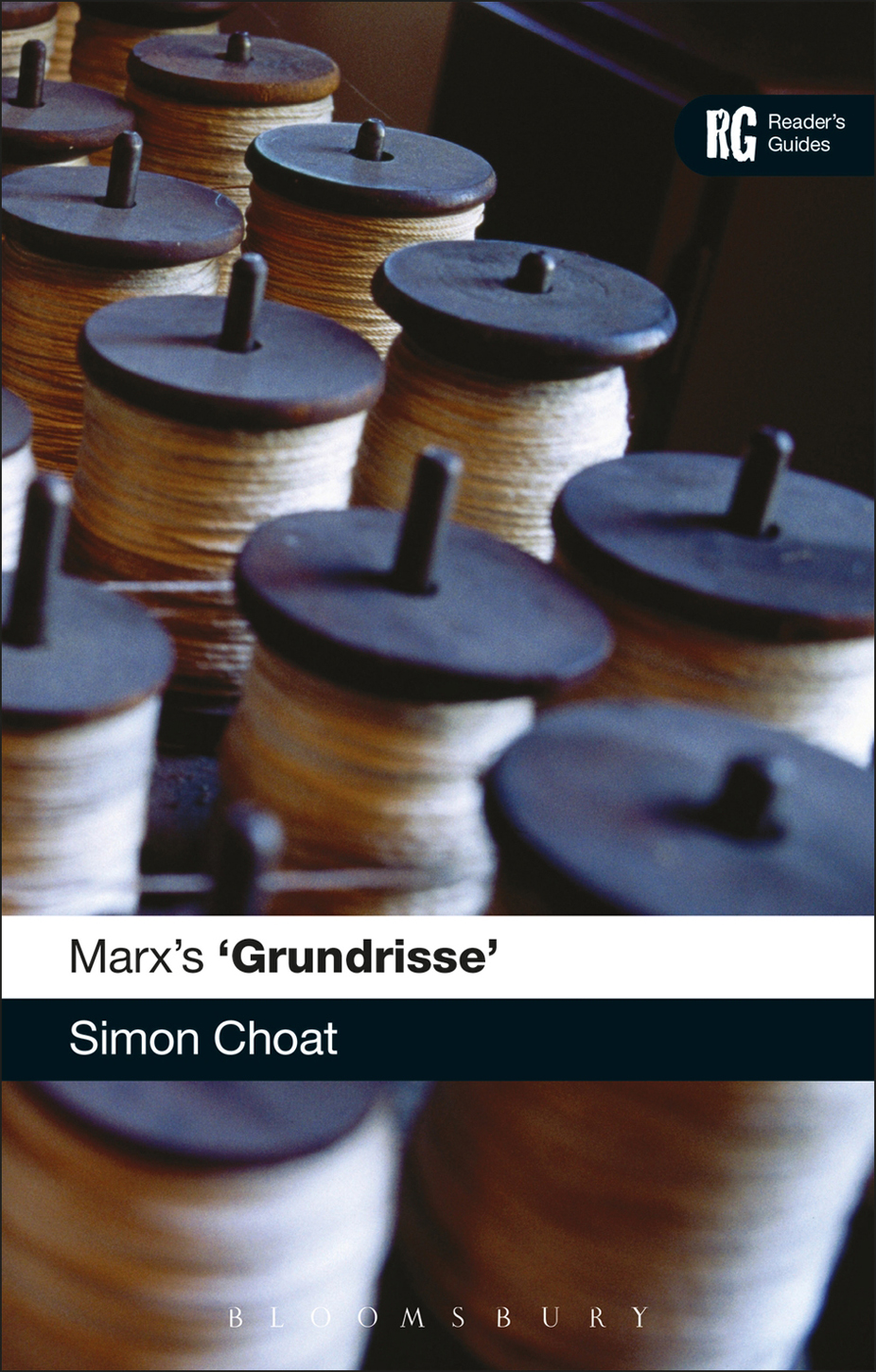

Marxs

Grundrisse

BLOOMSBURY READERS GUIDES

Titles available in this series

Aristotles Politics: A Readers Guide , Judith A. Swanson

Badious Being and Event: A Readers Guide , Christopher Norris

Berkeleys Principles of Human Knowledge: A Readers Guide , Alasdair Richmond

Deleuzes Difference and Repetition: A Readers Guide , Joe Hughes

Deleuze and Guattaris A Thousand Plateaus: A Readers Guide , Eugene W. Holland

Deleuze and Guattaris What is Philosophy: A Readers Guide , Rex Butler

Descartes Meditations: A Readers Guide , Richard Francks

Hegels Phenomenology of Spirit: A Readers Guide , Stephen Houlgate

Heideggers Being and Time: A Readers Guide , William Blattner

Hobbess Leviathan: A Readers Guide , Laurie M. Johnson Bagby

Kants Critique of Aesthetic Judgement: A Readers Guide , Fiona Hughes

Kierkegaards Fear and Trembling: A Readers Guide , Clare Carlisle

Levinas Totality and Infinity: A Readers Guide , William Large

Lockes Second Treatise of Government: A Readers Guide , Paul Kelly

Marx and Engels Communist Manifesto: A Readers Guide , Peter Lamb

Nietzsches Beyond Good and Evil: A Readers Guide , Christa Davis Acampora and Keith Ansell Pearson

Nietzsches Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Readers Guide , Clancy Martin

Rousseaus The Social Contract: A Readers Guide , Christopher Wraight

Spinozas Ethics: A Readers Guide , J. Thomas Cook

Wittgensteins Philosophical Investigations: A Readers Guide , Arif Ahmed

Wittgensteins Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus: A Readers Guide , Roger M. White

Forthcoming from Bloomsbury

Kants Critique of Practical Reason: A Readers Guide , Courtney D. Fugate

For Liz.

BLOOMSBURY READERS GUIDES

Marxs

Grundrisse

SIMON CHOAT

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

CONTENTS

S everal people have aided the writing of this book, either by reading and commenting on draft versions of the chapters or by discussing the Grundrisse with me. In particular, I would like to thank: John Grant, Julian Wells, Dave Tinham, John Spiers, Steve Keen, Judith Ryser, Daniel Fitzpatrick, Sam Halvorsen, Rick Saull, Bryan Mabee, and Jeff Webber. Only I am responsible for any errors in what follows.

Above all, I must thank Elizabeth Evans and, despite the fact that he actively hindered the completion of this book, William Choat.

CW: Karl Marx and Frederick Engels (19752005) Collected Works , 50 vols. London: Lawrence & Wishart.

C1: Karl Marx (1976) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy , vol. 1, trans. Ben Fowkes. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

C2: Karl Marx (1978) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy , vol. 2, trans. David Fernbach. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

C3: Karl Marx (1981) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy , vol. 3, trans. David Fernbach. Harmondsworth: Penguin

This book is a guide in the sense that a map is a guide to a particular territory. In the same way that you would not sit and home and look at a map instead of going for a walk, it is not my intention that you read this book instead of Marxs Grundrisse : it should be read alongside the Grundrisse to help you get your bearings or should be consulted at times when you are feeling lost. As with any map (especially for a territory as large as the Grundrisse ), not everything can be covered: the aim is not to reconstruct the Grundrisse but rather to guide you through its central concepts, claims and arguments.

The numbers in brackets in the text refer to page numbers in the Penguin edition of the Grundrisse :

Karl Marx (1973) , trans. Martin Nicolaus. London: Penguin.

This edition has been used because it is the most widely read and also because it is available for free on the Marxists Internet Archive. I am grateful to Martin Nicolaus for permission to quote from his translation. Occasionally, I have modified the translation and this is marked by tm . My own insertions into quotations are marked SC in text.

The Grundrisse is the name given to the notebooks that Karl Marx wrote in London in 18578. Its full title in German is It would be just as accurate, however, to call them a labyrinth: while logical and systematic, they also contain many dead ends, circular repetitions and confusing detours, and once you enter them you may regret having done so. In a letter of May 1858 to Friedrich Engels, Marx himself claimed that the manuscript on which he was working was a real hotchpotch ( CW40 : 318). The Grundrisse is nonetheless one of Marxs most important and influential writings, and a knowledge of it is vital for an understanding of his work as a whole. To begin guiding ourselves through this labyrinth, it will be helpful to place the text in its biographical, intellectual, and political and economic context.

Biographical background

Marx was born in Trier, Prussia, in 1818. In 1835, he went to study Law at the University of Bonn and after one year transferred to the University of Berlin. It was here that Marx developed an interest in the philosophy of G. W. F. Hegel: as he wrote to his father in 1837, he got to know Hegel from beginning to end, together with most of his disciples ( CW1 : 19). He also associated with and befriended some of those disciples, the so-called Young or Left Hegelians, who sought to develop Hegels philosophy for progressive or radical ends. Marx finished his studies in 1841, submitting a thesis to the University of Jena, which earned him a doctorate. Thwarted in his ambition to become a university teacher, he became a writer and editor for various short-lived journals, while continuing to write and publish more philosophical works. It was at those journals that Marx first began to investigate economic questions. As he later put it: In the year 184243, as editor of the Rheinische Zeitung, I first found myself in the embarrassing position of having to discuss what is known as material interests ( CW29 : 2612). His writings of the early and mid-1840s show his political development from a Hegelian-inflected radical liberalism to revolutionary communism.

The Rheinische Zeitung was eventually suppressed and, in 1843, a recently married Marx moved to Paris to work for another journal; here he became friends with Engels. Increasingly involved in radical politics, in 1847 both men joined the Communist League, for whom they wrote the Communist Manifesto , published in 1848 while revolutions swept across Europe. Ultimately those revolutions failed and Europe faced a counter-revolutionary wave of violent oppression. Marx was expelled from several European cities until, in 1849, he settled in London, where he lived with his wife and children until his death in 1883.

Intellectual context

Lenin famously claimed that Marxism was the legitimate successor to three currents of thought: German philosophy, English political economy and French socialism. The influence of each of these currents can be seen very clearly in the Grundrisse .

Hegel and dialectics

The German philosopher who most influenced Marx was undoubtedly Hegel. The nature and extent of Hegels influence is, however, a continuing source of debate. It is agreed that Marxs early works draw heavily on Hegel, but it has been argued most The Grundrisse must play an important role in this debate: clearly not an early work, it is nonetheless saturated with Hegelian terminology. Precisely what it is that Marx takes from Hegel remains a matter of dispute, but it is evident from comments in both correspondence and published works that the mature Marx valued Hegels dialectic, while nonetheless viewing it as deficient. In January 1858, while writing the Grundrisse , Marx wrote to Engels: If ever the time comes when such work is again possible, I should very much like to write 2 or 3 sheets making accessible to the common reader the rational aspect of the method which Hegel not only discovered but also mystified ( CW40 : 249).