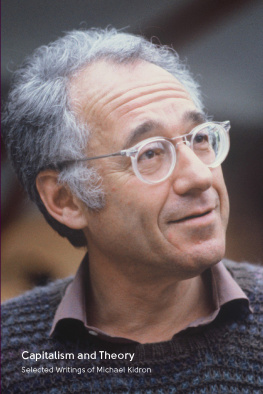

Michael Kidron - Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron

Here you can read online Michael Kidron - Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: Haymarket Books, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron

- Author:

- Publisher:Haymarket Books

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Chapter 1

Reform and Revolution:

Rejoinder to Left Reformism II [1961]

T his article will attempt to take up the case against Left Reformism, as it was presented by Henry Collins in the last issue of International Socialism , at the point where Alasdair MacIntyre left it. In doing so it will try to meet Collins on the grounds of his own choosing and, simultaneously, fill in some of the gaps left by MacIntyres more methodological treatment.

Although nowhere presented in sequence, Collinss argument amounts to a straight, rather crude, economism. By providing relatively full employment and a rising standard of living, capitalism can prevent the frustrations it engenders among workers from congealing into violent, revolutionary opposition. It has succeeded in doing so in the pastat least since the 1870sthrough exporting surplus goods and capital, and with them unemployment, to colonial and backward countries. It is doing so now by funnelling money from the private to the public sector and by expanding credit, that is, by a measure of planning; and it will be able to do so in the future by internationalising the planning process or, in greater detail, by strengthening international currency control, rationalising international trade, and so arming itself with the means to undertake the industrialisation of backward countries. This, in turn, will provide it with a vast new market. Naturally, planningwhether national or internationalis not welcomed by the orthodox, but they have no choice. The growing power of communism compels capitalism to adopt the very measures it dreads or, at least, inhibits its opposition to planning measures thrust on it by the workers. Ultimately, communist and working class pressure will result in the progressive assimilation of a degree of planning that will constitute socialism. And were therewithout revolution.

There are a number of points in Collinss thesis with which revolutionary socialists will want to quarrel. I shall deal with three of them: the role of planning in the stability of modern capitalism, the possibility of international planning today, and the problem of working class action. Two othersthe effect of development in backward countries on capitalist stability and the role of the statewill have to wait for another occasion.

Stability and Planning

For reformists, capitalist instability is subject to cure within the system; for revolutionary socialists it is not. The reformist will point to the absence of major slumps since before the war; the revolutionaryapart from a lunatic fringe who see in every visit to the labour exchange a prelude to hunger marcheswill accept the fact but question its relevance. Slumps have never defined the system; they merely indicated, viciously and publicly, its contradictory nature. Ultimately they derive from factors that are as inherent in capitalism today as they ever were, and which remain as powerful a source of instability.

Were it not that the productive forces of society are controlled by an infinitesimal minority of its members, the capitalists, the disposition of its resources over and above what is required for renewal would present no problem. It would conform to a pattern formulated by all in terms of present and projected needs and wishes. Were it not for competition amongst capitalists, whether organised in monopolies or not, there would be no compulsion for them to accumulate these surpluses and re-invest them in a constant, unplanned expansion of the productive structure. These statements are axiomatic in my argument. Without both these factors there would be no reason for the blind accumulation of capitalblind in the sense that it bears no immediate relation to the consumer needs of societythat has always defined the capitalist system. And it is this compulsive accumulation, the expansion of capacity in response to the exigencies of competition rather than to the needs of society, that has been the final cause of the periodic crises of overproduction that punctuated the development of capitalism until quite recently. It is also for Marx the underlying factor in the long-term decline in the rate of profit which, by lowering the ceiling of booms and shortening their duration, presaged for him a future of increasingly catastrophic slumps.

For Marxists, the problem presented by the absence of major slumps these last twenty years boils down to an enquiry into the factors that have fractured the compulsive accumulation-overproduction sequence. Is it planning, as Collins would have it, or something else? Logically, the factors fall into two groups: capitalism can either expand its markets or else destroy, partially or wholly, its constantly accumulating productive capacity. It is the first of these that has always appealed to reformist socialism: if only capitalists could be cajoled (right reformism) or forced (left reformism) into raising wages, a market would open up within the system which would both save it from crisis and benefit the working class. Thus Strachey. Thus Collins. But how useless! Were wages to increase at a greater rate than the increase in productivity, or the increase in the rate of exploitation, for any length of time, the rate of profit would fall and crises proliferate. Wages can, and have of course, been forced up, but alwaysin the long runwithin these limits where they are ineffective in opening up new markets, however important they are in humanising the condition of the working class. An alternative market, once highly favoured by reformists but now rejected in a rush of newfound international brotherhood, was that of the colonial world. This was the Fabianism of the Webbs. It was imperialism. But here too there was a catch. Although an effective evacuant of surplus capital for a time, imperialist investment merely postponed overproduction until the new capacity emptied its products on world markets. It could not serve as a permanent solution, because it disposed of capital accumulations in an essentially productive way.

This brings us to the second type of solution open to capitalism: the destruction or partial destruction of capital. Even in its most progressive phase, capitalism has resorted to destruction in order to sustain itself. Slumps were ruinous of capital; wars even more so. Advertising and the imposition of low standards (the interment of the perpetual electric light bulb or the ladder-resistant nylon stocking) play a small part in this today. Before taking up the discussion of the dynamics and limitations of this approach, a word or two need be said about a possible combination of the two types of solution, a combination that couples the search for markets with the control over accumulation. As Collins rightly points out:

[I]n the second volume of Capital Marx went on to show how the stability of a capitalist economy depended upon proportionate rates of growth being maintained in the sectors producing capital and consumer goods. Contrary to the teachings of the classical and vulgar economists there was no built-in tendency for such proportionate growth to occur, and crises of over-investment and under-consumption were, for all practical purposes, inevitable.

If the proportions could be maintained, capital prevented from flowing out of the heavy sector to consumer goods production in boom times, the system could be stabilised. This, Collins implies, can be assured through state intervention, which only now has become sufficiently massive and conscious to be effective. Perhaps. But, as this section will attempt to show, fixing the correct proportions is a function of the systematic destruction of potentially productive accumulation.

Capitalism is a naturally expanding system. In its industrial form it has spread from Britain both as an extension of the British economy (the Old Dominions) and as a defence against British encroachment and overlordship (large parts of Europe, for example). In many of the later, independent, and defensive capitalist economies (say in Germany or Japan), viability depended from the start on a degree of concentration of available capital and on a degree of interpenetration with the state, particularly with its active military arm, that were significantly different to what obtained in Britain. Naturally, foreign aggressiveness fed back into the leading capitalist countries: they met concentration of capital abroad with concentration at home, tariffs with tariffs, state intervention with state intervention, militarism with militarism.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron»

Look at similar books to Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Capitalism and Theory: Selected Writings of Michael Kidron and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.