Copyright 2018 by Jeffrey A. Engel, Merewether LLC, Timothy Naftali, and Peter Baker

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Modern Library, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

M ODERN L IBRARY and the T ORCHBEARER colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Engel, Jeffrey A., author.

Title: Impeachment : an American history / Jeffrey A. Engel, Jon Meacham, Timothy Naftali, Peter Baker.

Description: New York : Modern Library, 2018. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018034718| ISBN 9781984853783 (hardback) | ISBN 9781984853790 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: ImpeachmentsUnited StatesHistory. | BISAC: HISTORY / United States / General. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Government / Executive Branch. | HISTORY / Essays.

Classification: LCC KF 5075 . I 47 2018 | DDC 342.73/068dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018034718

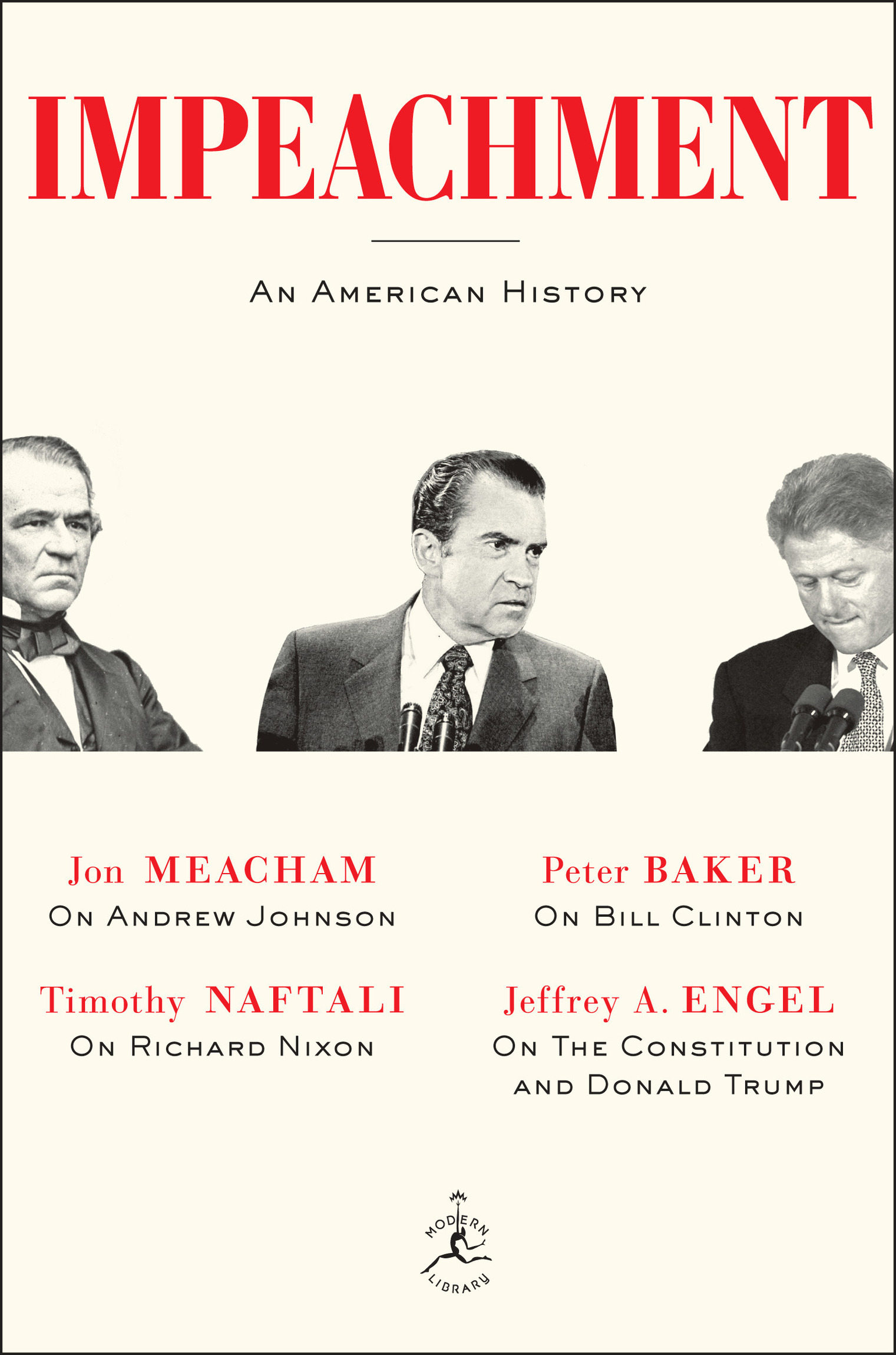

Cover photographs: National Archives / Getty Images (Andrew Johnson); The Washington Post / Getty Images (Richard Nixon); Associated Press (Bill Clinton)

I NTRODUCTION

It is rare, and for good reason. Impeaching a president is no small thing. Designed to check tyrants or oust corrupt leaders, the process of impeachment outlined in the United States Constitution nonetheless constitutes what Thomas Jefferson called the most formidable weapon for the purpose of a dominant faction that was ever contrived. It means, let us be blunt, nullifying the will of voters, and with it the basic foundation of legitimacy for all representative democracies. Hence its rarity. Only twice in two-plus centuries has the House of Representatives approved articles of impeachment against a sitting president, sending his and the nations political fate for trial in the Senate. A third time, certain impeachment and likely conviction were averted only at the eleventh hour by the resignation of a president who realized hed run out of options.

And that is it. Only three times in American history has a presidents conduct led to such political outrage or disarray as to warrant his potential removal from office, transforming a political crisis into a constitutional one. None has yet seen the process end in a presidents ouster. Andrew Johnson was impeached in 1868 for undermining Reconstruction and failing to kowtow to congressional leadersand, in a large sense, for failing to be Abraham Lincolnyet survived his Senate trial by the thinnest of margins. A vice president elevated following tragedy, he nonetheless made the office his own, bringing racial sensibilities and an idea of how to bring Confederate states back into the fold following the Civil Wara process broadly termed Reconstructionfar different from that the man he replaced likely would have pursued, and most surely at odds with the Republican majority in Congress. They wanted him out, but it was not clear hed done anything wrong or illegal, save not hewing to the party line. Trial in the Senate ensued. Then haggling, bribery, threats, and soul searching, and acquittal by a single vote. Unpopular in Washingtonalbeit increasingly popular throughout the defeated South, whose ideals he sympathized withJohnson remained to the end of his term, defiant, despised, and despicable. But still the president.

The same cannot be said for Richard Nixon, who, under fire for two years, ultimately resigned in August 1974 after the House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment for contempt of Congress, obstructing justice, and employing his executive power for personal and political gain. The scandal began with a bungled, politically inspired break-in at the Watergate office complex and blossomed as proof of Nixons complicity ultimately overtook his denials and dissembling. Upon reviewing the charges, one London newspaper quipped that in the time since George Washington first took the presidential oath in 1789 the office had progressed from a man who could not tell a lie, to one who could not tell the truth.

Even for a nation contemporaneously beset during the early 1970s by racial tensions, energy shortages, economic woes, and a military and humanitarian debacle in Vietnam, newly sworn-in president Gerald Fords assessment of Watergates broad impact was only partly true: Our long national nightmare, he told Americans the day Nixon left office, is over. Its legacy lingered. Respect for journalists initially flourished in Watergates wake, given the central role investigative writing had played in unraveling the scandal, but it did not last. The publics overall faith in the fourth estate weakened in the longer term as the cancer injected into the national consciousness by months of partisan slander and Nixons lamentations of the witch hunt waged against him slowly metastasized. Nixons supporters preferred to blame his ouster less on his own crimes than on those who reported them.

Watergate, by process of indignation, Republican senator Jesse Helms proclaimed, became the lever by which embittered liberal pundits have sought to reverse the 1972 conservative judgment of the people. Like-minded publisher Henry Regnery perceived an even deeper conspiracy. The most ominous thing about Watergate, he wrote, is that it clearly demonstrates that the press and the bureaucracy, working together, can destroy the president, and from now on, every president is going to have to take this fact into account.

Two generations later these charges still ring true in conservative circles. The Richard Nixon I knew had almost nothing to do with the Richard Nixon as portrayed in the media, columnist Ben Stein explained fully forty-one years after Nixons resignation, describing a wise but misunderstood man hounded from office by an urban and elitist news media determined to undermine his presidency and the traditional American values he espoused. Like the schoolyard bullies they are, Stein said, the media went after him for his vulnerability.

This is historical tripe, but effective when delivered to a receptive audience. Lies told often enough form a reality of their own, and Americans of all stripes struggled in the decades after Watergate to simultaneously process a presidents unprecedented resignation alongside broader changes in their nations economy, global role, and even ethnic and religious makeup. Conspiratorial explanations flourished in the combative political ecosystem that followed, with partisan critique ultimately proving more persuasiveand certainly better for ratings, first on radio and then on cable televisionthan the unraveling of complex facts. Small wonder, then, that the publics overall trust in journalists as the watchdogs of democracy has never again reached pre-Watergate levels.

Faith in government plummeted over the same period. In the broadest sense, one well-respected polling group concluded, public confidence in Americas leaders hasnt been the same since Nixons resignation. Before Watergate, more than half of Americans polled trusted their public officials to do the right thing. Never again would more than half of respondents say the same. There is a reason we apply -gate to any and all public outrages since: the maelstrom that consumed Nixons White House shattered public confidence in a manner impossible to ever again fully repair, setting the standard by which all ensuing scandals are measured.