Contents

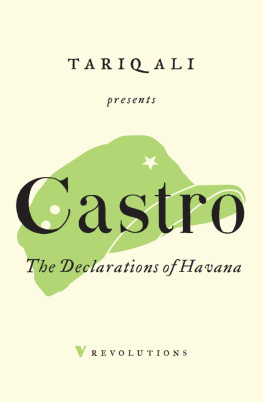

The Declarations of Havana

REVOLUTIONS

A series of classic texts by revolutionaries in both thought and deed.

Each book includes an introduction by a major contemporary writer

illustrating how these figures continue to speak to readers today.

The Declarations of Havana

Fidel Castro

INTRODUCTION BY TARIQ ALI

This edition published by Verso 2018

First published by Verso 2008

Introduction Tariq Ali 2008, 2018

Collection Verso 2008, 2018

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-138-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-139-3 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-140-9 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Bembo by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

CONTENTS

Explorations of the masterservant relationship have a long and distinguished pedigree in world literature, and its contradictions have been exposed in Al-Maari, Dante, Shakespeare, Cervantes and Goethe among others. In Cervantess masterwork, for example, a false oracle has informed the eponymous hero that his beloved Dulcinea can only be released if he is willing to sentence his servant Sancho Panza to receive thousands of lashes. Desperate for Dulcinea, the master agrees provided that he alone will administer the punishment. On a warm night his impatience gets the better of him. He rises from his bed and prepares to flog the unwitting Sancho Panza. Imagine the masters astonishment when the servant, instead of submitting quietly to violence, knocks him down. Cervantes writes:

Don Quixote: So you would rebel against your lord and master, would you, and dare to raise your hand against the one who feeds you.

Sancho: I neither make nor unmake a king, but am simply standing up for myself, for I am my own lord.

Here in a nutshell is the story of the Cuban Revolution. With the ending of direct colonial rule in the decade that followed the end of the Second World War, the overwhelming majority of countries in the three exploited continents ceased to be colonies in the usual sense. The United States, unlike its European cousins, had always preferred the indirect mode of domination, one which soon became the norm: formally independent and sovereign states, but heavily dependent on their metropolitan masters. An overblown and parasitic bureaucratic machine inherited from the colonial period presided over a backward socio-economic structure.

The function of these formally independent states was to serve the economic needs of the imperial powers, at the cost of their own political and economic sovereignty. This often resulted in a plantation culture ruled by the production of a single commodity sugarcane, in the case of Cuba or the extraction of mineral and oil resources, as in Africa and the Middle East. This structure discouraged any real attempts to generate an autonomous process of industrialization. India and Brazil were exceptions in this regard, but the autonomy on display in these countries did little to affect the global structure of domination.

In South America a governing creole elite, ruling in most cases with US political and military support, held the continent with relative ease. Rebellions, such as that led by Sandino in Nicaragua, were isolated and crushed. Physical and cultural repression of the indigenous population (with the exception of Mexico) was regarded as normal. Populist experiments (Argentina and Brazil) did not last too long. Few thought of Cuba as the likely venue for the first anti-capitalist revolution. For one thing, it was too close to the United States; moreover, the scale of US investments on the island was such that the corporations were unlikely to relinquish their grip. And if there was real trouble the Marines would undoubtedly be despatched to calm the natives in time-honoured fashion.

It didnt quite turn out like that. The small band of guerrillas led by Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos were initially seen as little more than an irritant. Batista, the Mafia-backed dictator in Havana, denied that there was any serious unrest in the country, and it was an enterprising US journalist who brought the first real news of armed struggle in the Sierra Maestra to the world. New York Times reporter Herbert Matthews practised his craft in a world slightly different to our own. For one thing, the newspaper of record, as the Times defined itself, generally permitted its journalists the creative freedom to explore new terrain or investigate the effect of US interventions in its South American backyard. His series of articles for the paper trumpeted the prologue of the Cuban Revolution.

The Cuba in which Matthews arrived in 1957 was the product of a turbulent past. La Isla Fiel (The Faithful Island) of Spanish imperial folklore, it had, under the leadership of its landed gentry, united against Spanish rule in the 1860s. After a decade of savage Spanish repression, the revolt was crushed. The decline in sugar prices triggered a new uprising in 1895 as plantation owners rallied to the cause of independence. The Spanish fought bitterly, and herded hundreds of thousands of Cubans into reconcentrados, concentration camps (their first appearance on the globe), where they languished and died. Twenty per cent of Cubas population (350,000) died during the three years of conflict. US entry into the war led to a Spanish defeat, but the ordeal had seriously weakened Cubas landowning class, which became incapable of resisting the establishment of a de facto US protectorate, with a permanent military base at Guantnamo. The Catholic Church was weak (three-quarters of the priests were foreigners), and incapable of shoring up the new regime. The Cuban landed oligarchy had virtually disappeared from the political landscape after another catastrophic slump in sugar prices following the First World War. This removed the only local force that could have blocked a revolution, as it had done successfully elsewhere in the continent.

Lacking cohesion, the urban rich were initially happy sub-alterns of the US corporations that occupied the island. US capital invested in Cuba was seven times greater than in the rest of South America. In the 1950s a building boom helped create a new class of Cuban businessmen. Occasionally they dreamed of grandeur and used their large fortunes to buy back the old plantations from US companies, but always stressed their own subordination to the imperial presence. They were parasites and happy with the niche that had been granted them. The ennui that pervaded this class forms the subject matter of many Cuban novels of the period.

Cubas fake parliamentary regime was venal. Its politicians regularly looted the countrys exchequer, and gang wars ravaged the cities. It was, in short, a complete debacle. Unsurprisingly, General Batistas second coup in 1952 met with no resistance from the political establishment, but nor did they give him fulsome support. He was regarded as an adventurer (in 1933 as a sergeant he had, together with student groups, organized a successful revolt against his own High Command) and considered untrustworthy. Because of his dark skin he was not permitted entry to the Havana Club, where the rich made business pleasurable.

REVOLUTIONS

REVOLUTIONS