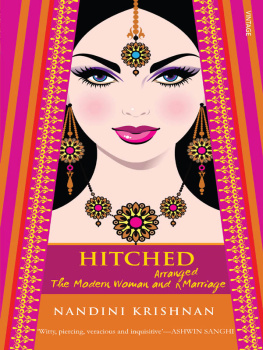

| Invisible Men: Inside Indias Transmasculine Network |

| Nandini Krishnan |

| Penguin Random House India Private Limited (2018) |

|

Female-to-male transgender people, or transmasculine people as they are called, are just beginning to form their networks in India. But their struggles are not visible to a gender-normative society that barely notices, much less acknowledges, them. While transwomen have gained recognition through the extraordinary efforts of activists and feminists, the brotherhood, as the transmasculine network often refers to itself, remains imponderable, diminished even within the transgender community. For all intents and purposes, they do not exist. In a country in which parents wish their daughters were sons, they exile the daughters who do become sons.

In this remarkable, intimate book, Nandini Krishnan burrows deep into the prejudices encountered by India's transmen, the complexities of hormonal transitions and sex reassignment surgery, issues of social and family estrangement, and whether socioeconomic privilege makes a difference. With frank, poignant, often idiosyncratic interviews that braid the personal with the political, the informative with the offhand, she makes a powerful case for inclusivity and a non-binary approach to gender.

Above all, she asks the question: what does manhood really mean?

Foreword

Fluid Has Direction

This is the part of a book I usually skip. After the prologue, which is unnecessary, and the blurb, which is unnecessary and a lie, and the introduction, which is a ruse promoted by academics to appear in books that people actually read, the foreword has to be the most spurious thing inside a book. But it has one respectable qualitythe writer of the foreword usually is some kind of an expert, related in some form to the subject matter of the book, and he says scholarly things about his domain. But this foreword does not possess even that single redeeming quality. In fact it did not occur to me until I began to read Nandini Krishnans manuscript that there can be genders within transgenders.

What did I think gender was? Male, female and a certain ambiguity? But then what exactly is the ambiguity? How many times have I met those amiable muscular Tamil eunuchs in saris who have no ambiguity at all, who are rather very sure about who they arewomen trapped in male bodies?

I first met them when I was twenty. Savvy magazine sent me to a small Tamil village called Koovagam to cover an extraordinary festival. Transwomen and transvestites from all around the nation arrived in spectacular bridal wear, and they stood in line to marry a minor god called Aravan. As the story goes, or at least as it was told to me then, during the Mahabharatas decisive Kurukshetra war, the good guys were losing and the sages said that for things to turn around, a perfect warrior had to be sacrificed. There were only three men who qualified as perfect warriorsKrishna, who was a god and indispensable; Arjuna, who was the hero and indispensable; and Arjunas son, Aravan, who was hence doomed. He was a virgin and he wished to enjoy sex before his death. So Krishna transformed into a beautiful young woman, Mohini. The transwomen of India worship Aravan because he married a woman knowing that she was once a man. And that is why they, too, marry him. On the wedding night, the brides offer free sex to the men and so the village swarmed with Tamil men in lungis, many of whom abused and molested the new brides of Aravan.

A quality of Tamil Nadu is that its transwomen are a part of mainstream life, yet they attract a dark and terrifying malice in Tamil men (once, in a train, a young and coy transwoman was seated beside me; a man came in with his bags and upon finding her, he kicked her on her chest, for no reason at all apart from that the fact that he could, culturally, kick her and get away with it). In Koovagam, after the raucous bridal night, the brides become widows to mark the death of Aravan. They wear white saris and they beat their chests and wail. As you keep staring at them, you slowly realize it is not for some mythical minor god that they mourn. They cry for their entrapment in male bodies. My time in Koovagam made me comfortable with them, and a few months later in Mumbai, at a traffic light, when a transwoman asked me for money and I didnt have change, I gave her twenty and asked her for ten back, which greatly baffled her.

The lives of transwomen are somewhat better now. Among transgenders, transwomen are the normal people. The transgenders we think we know are in actuality transwomen; men who strive to become women. But there is the other kind, which is the subject of this book.

I have for long considered men and women who are normal, who are biologically, mentally, indisputably men and women, who claim that gender is a spectrum, as charlatans who want to state something esoteric even though they dont know what they are talking about. Gender is not a spectrum; gender is a definite state of being. The body is the spectrum. Some men and women are trapped in the wrong bodies, and they then proceed to transit. Transition is not a spectrum; transition is movement towards certainty. We imagine the people in transition as a single collective organism in weird clothes, whom we then place in our minds as the middle-people. What does not occur to us is that the transition is not only continuous, it also has a direction. To be precise, it has two directions.

It is not only men who strive to become women; there are millions of women who wish to become men. This exquisite book tells the stories of some of those women as they begin to transformthe hope and force of inevitability that subsume the torture of it all. You will read about women who use the latest medical advances to liberate themselves from their gorgeous female shape, who will cut away their breasts, destroy their long flowing hair, make stubbles spring on their faces, and fix agonizing penises.

Nandini uses a technique popularized by V.S. Naipaul and Svetlana Alexievichof telling the stories of people through their own authentic voices. And she is such a trustworthy researcher that these stories she is about to tell also serve as an anthropological survey of Tamilianshow they deliver jokes, how they hurt and how they are fused with their grandparents, and in what ways they are subtle and what ways melodramatic. This book is, at times, the Malgudi Days of transmen.

There are, of course, large swathes of stories that she narrates herself, through her own voice. Her artistic talent alone would make the reading of this book an important joy, but there are two other qualities that I feel are more influential. She is a delinquent. No interesting aspect of life escapes the delinquent. Also, she does not need the farce of compassion to respect people. As a result, the book that you hold does not contain even a moment of the feudalism of the lucky masquerading as sympathy for the unlucky.