Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

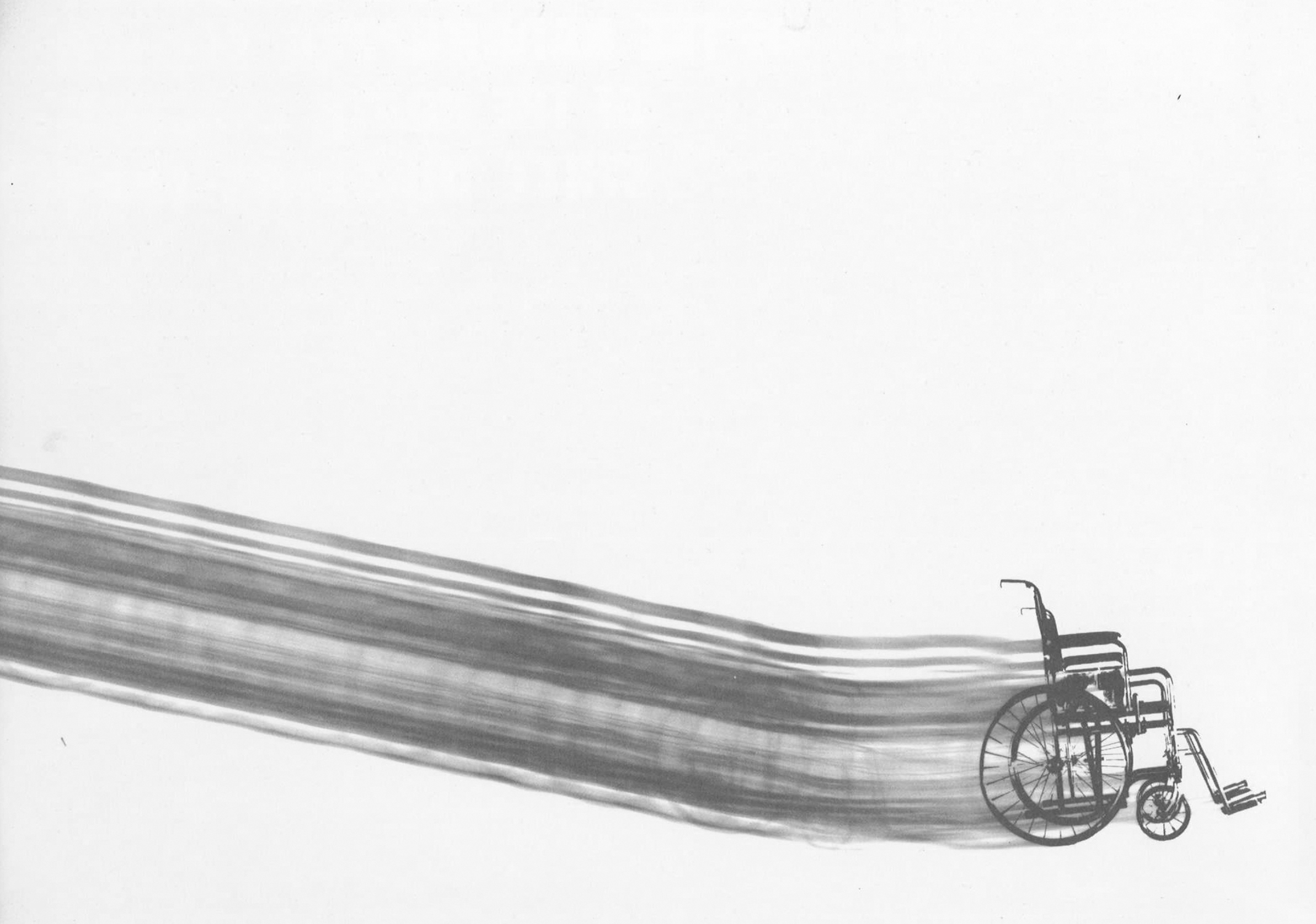

ACCESSIBLE AMERICA

Accessible America

A History of Disability and Design

Bess Williamson

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2019 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Williamson, Bess, author.

Title: Accessible America : a history of disability and design / Bess Williamson.

Description: New York : New York University, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018012212 | ISBN 9781479894093 (cl : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : People with disabilitiesUnited StatesHistory. | Barrier-free designUnited States. | Universal designUnited States.

Classification: LCC HV 1553 . W 55 2018 | DDC 362.4/047dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018012212

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

In Memory of Philomene Asher Gates

CONTENTS

Introduction

Disability, Design, and Rights in the Twentieth Century

Every day in my city, I use the things I write about. I am not disabled in any conventional sense of the term, but I use curb cuts, feeling under my feet concrete grooves and rubberized bumps that signal a shift in terrain. I see parents pushing strollers, travelers wheeling bags, and street vendors and movers with hand carts all using curbs and ramps to go about their daily tasks. Returning an armful of books to the library, I hip-check the large metal button that opens the automatic door. In a crowded bus, I look up at the LED words telling me (if they are working) which stop is next. As a historian of design, I can even note a few relevant works from design history: the long, smooth ramp of Frank Lloyd Wrights 1943 Guggenheim Museum, not designed explicitly as a wheelchair ramp but suggesting alternative means of traveling up and down a grand building; the round Honeywell thermostat, easy to read and rotate, designed by ergonomics pioneer Henry Dreyfuss in 1948; and the black rubber-handled OXO Good Grips vegetable peeler, developed in 1989 by Betsey Farber, who had arthritis, with her husband, Sam, a product designer. Some sites surprise me with unconventional approaches to accessibility, like the gentle bird-chirping and wind-chime sounds piped in to mark key pathways on the campus of San Francisco State University, or the light displays along quiet underground walkways between terminals at the Detroit Airport that provide a break from the audio and visual overload of the rest of the airport. More commonly, features of accessible design seem to materialize the decades of struggle that it took to put them into place: subway elevators reeking of pee or out of order; accessible toilets repurposed for storage or inexplicably locked.

Accessible designdesign that is usable for people with physical, sensory, and cognitive disabilitiesis a ubiquitous part of the contemporary built environment in the United States and, increasingly, the world. Over the last half century, legal and social mandates for disability inclusion have brought about changes in nearly every public space in the country and influenced a new range of forms in office equipment, household products, and personal technologies. Initial efforts to address physical barriers in public spaces came in the 1940s and 1950s, partially in response to the return of disabled veterans from World War II and the well-publicized effects of the polio epidemic.

The objects and architecture we describe today as accessible are artifacts of a period in which many Americans revised their perceptions of disability and the place of disabled people in U.S. society. The idea that disabled people could and should participate in public life took hold in the medical, legal, and social mainstream of the twentieth century in a shift that Henri-Jacques Stiker refers to as making disability ordinary: rather than pitied or reviled, Stiker writes, in this new era the disabled were to be folded into the commonplace through rehabilitative efforts to normalize. Design played a significant role in this task of normalization. The resulting designs, however, were often controversial or ineffective. Often these features were added reluctantly, as technical afterthoughts, or were difficult to use, requiring people who needed them to ask or search for supposedly accessible services. Regulations on access addressed only a limited segment of the disabled population when they prioritized physical mobility more often than other concerns such as communication, comprehension, or social dynamics.

This history finds in the concept of access a story of twentieth-century design politics. As Langdon Winner wrote in his 1986 essay Do Artifacts Have Politics?, the political implications of technologies are as likely to be a product of their circumstances as inherent to their design. In contrast to the most overt of political technologies, such as large-scale systems that are compatible with strong, centralized authority, the politics of what Winner calls technical arrangements are less apparent, seemingly minor details in the construction of everyday spaces and things. The means by which these arrangements became rearranged was highly political as well. Initial legal measures had little material effect when accessibility requirements were rarely followed or enforced. It was not until citizen activists pushed for specific and stringent enforcement that meaningful change began to appear. Once in place, the artifacts of access took on new meaning, particularly for opponents who saw accommodations as moves of a nanny state intervening in private life and business. As Winner might point out, advocates of access and their opponents shared a deeply political reading of everyday design.

Access became a measure of new priorities in design of the twentieth century. Design, a catchall term for the many practices of shaping and organizing human tools and environments, has often been deployed within modern agendas of organization and standardization. Whether in reform of public housing and industrial work conditions, or in more recent plans to improve environmental performance, mediators suggested that design was a tool of social improvement. When it came to disability, as medical professionals, veterans advocates, and community activists pointed to stairs, buses, parking lots, phone booths, and everyday appliances as barriers to inclusion, they defined the social experience of disability through the material world. Through this line of thinking disability itself could be seen as a product of design, and design the potential maker of an inclusive society.

Efforts to improve access contributed a new sense of the social potential of design, but also revealed deeply held American beliefs about technology, space, and society. From the start, conversations about access touched a sensitive nerve in American political discoursenamely, the bias against collectivism and shared resources, rather than private property and individual economic power. Throughout the late twentieth century, advocates favored approaches that centered on an individual, economically mobile actor rather than a figure representing general social welfare. These concerns recall other design histories in which U.S. government agencies and consumers have favored approaches that center individual rather than collective participation. This preference did much to shape the realities of the American home and its gender roles. In the early twentieth century, efficient, modern conventions such as commercial kitchens and laundries lost favor in a consumer culture that painted ideal middle-class households as spaces where an individual woman performed housework using her own appliances. As the first three chapters of this book show, this normative household image also shaped prescriptions for the kinds of accessible design that should be developednamely, that which maintained expectations of race, class, and gender roles.