Copyright 2016 by Peter Fritzsche

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Amy Quinn

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fritzsche, Peter, 1959 author.

Title: An iron wind: Europe under Hitler / Peter Fritzsche.

Description: New York: Basic Books, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016018828 (print) | LCCN 2016025604 (ebook) | ISBN 9780465096558 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 19391945Occupied territories. | World War, 19391945Europe. | World War, 19391945Personal narratives, European. | World War, 19391945Social aspectsEurope. | Civilians in warEuropeHistory20th century. | ViolenceSocial aspectsEuropeHistory20th century. | War and societyEuropeHistory20th century. | Hitler, Adolf, 18891945Influence. | EuropeSocial conditions20th century. | BISAC: HISTORY / Modern / 20th Century.

Classification: LCC D802.A2 F77 2016 (print) | LCC D802.A2 (ebook) | DDC 940.53/4dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016018828

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Franziska, my love

CONTENTS

Table of Contents

Guide

After I completed my book Life and Death in the Third Reich and corrected the galleys, I left for Germany with my children for a semester-long sabbatical. When I got to Berlin in January 2008, I simply kept on going, researching the book I had just finished, prowling the archives, looking for stories, trying to find more voices to help me understand the calamity of World War II and the Holocaust. At the same time, I became increasingly aware of how contemporaries themselves recorded events and established archives in order to make sure that a history of the war could be written. Some of this activity was undertaken by Germans, usually as they looked forward to a great victory; much of it was undertaken by Jews as they contemplated the destruction of their families in the ghettos into which they had been shoved. Slowly, I organized my thoughts and conceived of a book that would explore how people in World War II struggled to make sense of the murderous events occurring around them. I wanted to understand what people thought they were seeing in German-occupied Europe. Civilians constituted the great majority of the victims in the war, but they also deliberately refused to see or they misunderstood what they did see. Ordinary men and women thereby contributed to the horror that engulfed Europe. Even patriotic narratives of anti-German resistance mirrored Nazi views of the world in crucial ways. This book is about the wartime experience of civilians, the often dubious parts they played in the war, and the ways they approached their neighbors and the groups persecuted by the Germans. The violence of the war was so extensive that people tried to contain it by separating themselves from the fate of others. World War II revealed the broad collapse of structures of empathy and solidarity in a way that World War I never did. People helped each other, but they also betrayed each other. They were blinded by myopia, but they were also brutally frank and occasionally startlingly incisive. An Iron Wind tells the story of how people struggled to find meaning in World War II. It tries to listen into the talk in wartime.

This book has been a long time in the making, and I finally began writing in 2014. I would not have completed this book without the love and support of my wife, Franziska, to whom it is dedicated. She is my great love. I have always been nourished by my children, Lauren, Eric, Elisabeth, Joshua, and now Matteo, whom I neglected but with whom I also sometimes, hopefully often enough, played hooky. I am deeply grateful to my colleague Harry Liebersohn and my mother, Sybille Fritzsche, for reading and commenting on the manuscript. Many thanks to my agent, Andrew Wylie, for his consistent support and to Brian Distelberg at Basic Books for his extraordinary suggestions on how to improve my argument. Many years ago, Matti Bunzl and the Jewish Studies reading group at the University of Illinois provided an early and hugely welcome forum for what were still my hugely rough ideas. My thanks also to Geoff Eley, Anne Fuchs, and Michael Geyer. Many people, most of whom I know only through their words, were in my thoughts as I wrote this book; I want to name one of them: my father, Hellmut, himself a World War II veteran. I have become a better scholar and writer thanks to these collaborations, but the errors and problems that remain are all mine. Ultimately, no book on World War II can ever be finished or be adequate in any meaningful way, which is both the origin and the conclusion of An Iron Wind.

Urbana

March 23, 2016

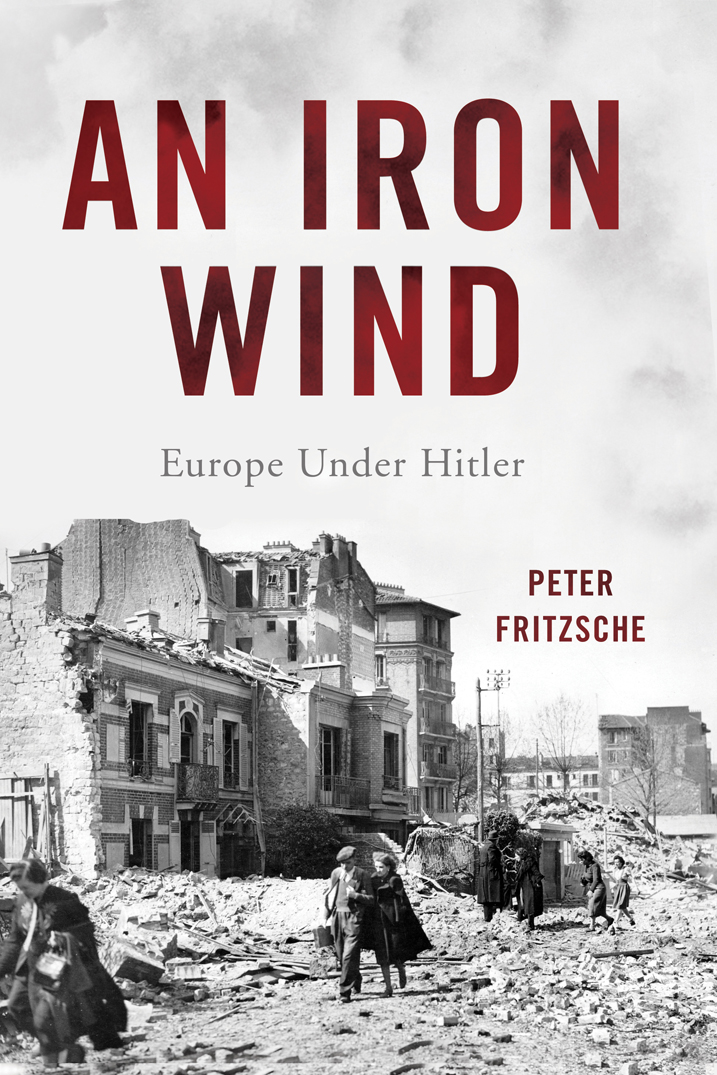

Stalingrads World War II memorial is inscribed with the words An iron wind beat into their faces, followed by but they all kept marching on. For German-occupied Europe, the first part is true; the second part is not. The war was an iron wind, massively and unrelentingly destructive on the home front as well as the battlefield. But not everyone marched. People were deported, enslaved, and massacred. Others crouched down to find shelter from the wind of war, or they turned with the wind to collaborate or somehow make do. Those who did fight did not always do so from the wars beginning or find themselves alive at its end. This book is about how people scattered by the iron wind of Germanys war in Europe in the years 19391945 came to intellectual grips with the most terrible conflict in modern history.

When World War II came, it smashed through the expectations about battle that had been formed during the Great War that preceded it. The war marched into civilian lives in an unprecedented way. Not only were cities bombed but homes invaded, neighbors arrested, and Jews deported. The iron wind also unsettled and then blew apart notions of empathy and solidarity. In no previous modern war was the casualty rate among civilians so high and suspicion about neighbors so acute. In dramatic contrast to the fallen uniformed soldiers mourned after World War I, the vast majority of the dead in World War II were noncombatant men, women, and children, some 20 million in all. Nearly 1 million civilians died in aerial bombardments, with tens of millions more left homeless, but the air wars casualties were not nearly as high as Europeans anticipated at the outbreak of the war. Instead, thousands upon thousands of civilians were slaughtered as hostages, as Germany retaliated against partisan attacks on its soldiers, or were killed simply for being Polish or Jewish. Nearly 1 out of every 5 Poles perished during the conflict, in contrast to 1 in 50 who did so in France. Three-quarters of Europes Jews, a total of 6 million people, did not survive; they were the neighbors most likely to be deported and murdered. The war turned military barracks such as those in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz into civilian concentration camps. It is imperative to reconsider World War II not simply as a military conflict but as an extraordinary assault on civilians.