WHEEL FEVER

WHEEL FEVER

How Wisconsin Became a Great Bicycling State

Jesse J. Gant & Nicholas J. Hoffman

Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

2013 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

E-book edition 2014

For permission to reuse Wheel Fever: How Wisconsin Became a Great Bicycling State (ISBN 978-087020-613-9; ebook ISBN 978-0-87020-614-6), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

wisconsinhistory.org

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Societys collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

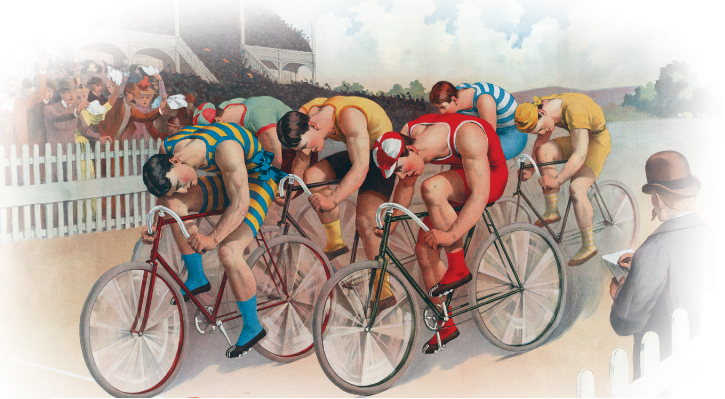

Cover: Detroit Lithograph Company, 1895. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsa-08935

Designed by Authorsupport.com

17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Gant, Jesse J.

Wheel fever : how Wisconsin became a great bicycling state / Jesse J. Gant and Nicholas J. Hoffman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87020-613-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. CyclingWisconsinHistory. 2. WisconsinHistory. 3. WisconsinSocial life and customs. I. Title.

GV1045.5.W62G36 2013

796.6409775dc23

2013007080

Contents

To Randy and Marcy Gant

and Kristi Helmkamp

FOREWORD

W hy a book about cycling in late nineteenth-century Wisconsin? Granted, the bicycle is widely considered one of the greatest inventions of all time, cleverly exploiting the clean and abundant supply of willpower to provide cheap and efficient transportation, not to mention healthful and enjoyable recreation. And those were the crucial years that witnessed the transformation of the first crude miniature carriages into something very much resembling contemporary bicycles. But, still, why focus on Wisconsin?

The authors of Wheel Fever, Jesse Gant and Nicholas Hoffman, explain that Wisconsin has become a leading cycling destination for outdoor enthusiasts, offering beautiful scenery, an inviting rolling terrain, and a vast network of cycling paths reclaimed from abandoned railroads. They further assert that the current popularity of cycling has something to do with the states long infatuation with the sport, dating back to the original boneshakers of 1869.

As a bicycle historian who learned how to bicycle in the capital city of Madison less than a century after Joshua G. Towne introduced the sport to the state, I am, of course, partial to the books premise. But some might question whether the books geographical scope is sufficiently broad to tell the story of cyclings rise.

The authors, both passionate riders and loyal native sons, readily concede that the states historical ties to the mechanical horse are not particularly striking. After all, the first waves of velocipede mania, emanating from France, struck the eastern seacoast before making their way west in the late 1860s. And the bicycle revival a decade later, triggered by the introduction of the British high wheeler, likewise started in the East, with Boston serving as its hub. To be sure, Wisconsin did keenly experience the great bicycle boom of the 1890s, but so did every other state, notably neighboring Illinois, home to the manufacturing center of Chicago.

Still, there is a Wisconsin-based story to trace and tell, and the authors have done so with admirable skill and devotion. It would be a great mistake to infer that this book is narrowly focused or strictly of regional interest. On the contrary, it gives an excellent overview of bicycle development during a crucial period when the curious two-wheeler was still vying to prove its lasting value.

The narrative also explores broad themes that would greatly influence the development of the nation as a whole, such as the birth, growth, and operation of an important industry, the rise ofand resistance towomen and black cyclists, the campaign for better roads, and the establishment of a popular spectator sport.

Moreover, as it turns out, the Wisconsin-rooted characters presented here were highly representative of their peers elsewhere. Joshua Towne may have been a clerk at the Milwaukee office of the American Express Company, but he was also the spiritual brother of hundreds of young office employees the world over, for whom the velocipede represented an exciting and alluring new way to exercise, travel, and socialize. Only a year before Townes exhibition, E. Vallot of Paris wrote Pierre Michaux, the pioneer bicycle manufacturer of the same city, asking for a payment plan. I have about 85 colleagues, he pleaded. Most are young people, and the majority of those would certainly become buyers if offered such terms.

Similarly, Terry Andrae, a.k.a. The Flying Badger, was in many ways a typical wheelman of the 1880s. Young, athletic, and privileged (his fathers factory in Milwaukee produced bicycles and tricycles), he was an ardent proponent of the new-style bicycle with its towering and daunting profile. Unlike the discredited boneshaker, it truly was a roadworthy, if accident-prone, vehicle, though it renounced any aspiration to serve as the peoples nag. On the contrary, it was unabashedly recreational in nature, deliberately imposing and exclusive. For Andrae and similar devotees on both sides of the Atlantic cycling offered speed, adventure, and glory.

Despite its elitist nature, the high wheeler laid the technical and social foundation for the great bicycle boom of the 1890s, a phenomenon that would touch nearly every segment of American society and shape the nations course for decades to come. And as the title Wheel Fever suggests, the boom era is in fact the heart of this book. Many of the Wisconsinites we meet here were not only representative of their generation but were also genuine players on the national scene. The Janesville-raised temperance leader Frances Willard, for example, wrote a popular book encouraging women to take to the wheel. And Milwaukee-born racer Walter Sanger dominated the competitive sport at its peak.

This is also the part of the narrative where the authors present their most compelling research and analysis. They show how the cycling movement, even as it grew to include ever-larger cross sections of the American population, was still very much a product of its times, subject to powerful reactionary forces bent on suppressing its liberating and democratic tendencies.

I thank and congratulate Jesse Gant, Nicholas Hoffman, and the Wisconsin Historical Society Press for producing this valuable and welcome addition to cycling literature.

David V. Herlihy

Boston, Massachusetts

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I t is a tremendous pleasure to thank the people who helped bring Wheel Fever into existence. We first started thinking about this book during the summer of 2009, andas is often the case with this kind of workwe have incurred many debts. We would like to take this opportunity to acknowledge those who helped us, directly and sometimes indirectly, along the way.

We start with the number of excellent mentors and teachers we have worked with these past few years. Scholars and writers who taught us to become better historians include: Jasmine Alinder, Bill Cronon, Jack Dukes, Kristen Foster, Michael Gordon, Susan Johnson, Will Jones, Steve Kantrowitz, David McDaniel, Aims McGuinness, Steve Meyer, Jennifer Morgan, Monica Rico, Amanda Seligman, and Daniel Sherman. Michael Gordon, in particular, deserves our special thanks. He made this a better book not only by laboring through a number of early drafts but also by challenging us to expand our thinking whenever and wherever it was possible. We also want to offer a special thanks to David Herlihy, our foreword writer, who read an early version of the book, travelled to visit us in the middle of Hurricane Sandy, and has proven himself to be a wonderful friend and supporter. Finally, Greg Bond wrote a PhD dissertation examining race and sports in the late nineteenth century that we found helpful for our analysis. All have inspired us to become better thinkers and writers, and we are grateful that they have invested so much time and energy in us.

Next page