All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace for providing the graphs that appear in this book.

The map on is reproduced courtesy of The Map Company, copyright Kappa Map Group LLC. Used with permission.

Endpaper map by Mapping Specialists, Ltd.

Name: Kleinfeld, Rachel, author.

Title: A savage order : how the worlds deadliest countries can forge a path to security / Rachel Kleinfeld.

Description: First edition. New York : Pantheon Books, 2018. Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018014527. ISBN 9781101871997 (hardcover : alk. paper). ISBN 9781524746872 (ebook).

Subjects: LCSH: Internal securityCross-cultural studies. Human securityCross-cultural studies. National securityCross-cultural studies. ViolencePrevention. ViolenceGovernment policy.

Classification: LCC HV6419 .K54 2018 | DDC 363.32/17dc23 | LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2018014527

may your efforts be rewarded.

INTRODUCTION

It is impossible to move tons of cocaine, launder thousands of millions of dollars, and maintain a clandestine organization of several hundred armed persons without a system of political and police protection.

YOLANDA FIGUEROA, A JOURNALIST MURDERED ALONG WITH HER HUSBAND AND THREE CHILDREN IN MEXICO, DECEMBER 1996

Ebed Yanes knew better than to leave the house at night. He was a diligent student, the kind of teenager who washed his fathers car every Sunday before church. But he was also fifteen, and it was an early summer Saturday. A girl he knew from Facebook had suggested a rendezvous. After his parents had gone to bed, Ebed snuck out and drove off on his fathers motorcycle. He followed the roads for a while looking for the girl. He couldnt find her. He sent her a text message telling her that he had to return home.

The next morning, his father noticed the car was unwashed. He called the guard booth at the entrance to their gated community. The guard said that Ebed had left around midnight and hadnt returned. Ebeds parents tried to stay calm. They checked the childrens hospital, then the jail. Next, they stopped at the police homicide division. Ebeds parents finally found their only son in the morgue, with a broken jaw and a bullet wound near his mouth.

In Honduras, one of the most violent countries on earth, Ebeds killers might have been members of a gang or a drug cartel. The police mentioned they could have been at a party near where the body had been found: in a country with so much impunity, small arguments mixed with alcohol often led to death. As Ebeds father walked the street where his son had last been alive, a neighbor poked out his head. He had heard shots the night before, he explained, and saw soldiers prodding a splayed body with their rifles. The neighbor handed Ebeds father the empty bullet cases he had collected after the soldiers had left.

As a senior fellow at a Washington think tank, I advise governments and philanthropists on how major social change occurs in democracies, particularly how to build security, improve governance, and deepen justice in badly governed countries. My desk is cluttered with studies analyzing terrorism, fragile states, insurgencies, and war. But the dirty secret is that we know surprisingly little about how to solve these problems. Policies often simply mimic the strategies used in functional countries. We had no proof, for instance, that the program used to train Germanys police would be effective in Afghanistan. But that was the policy Europe and America decided would mend the warring country after the United States and allied forces invaded in 2001. Its the sort of idea that gets trotted out again and again.

Nearly all the research we have about violence offers insight into countries at war. Today, however, most violent death looks like Ebeds murder in Honduras. Since the end of the Cold War, wars between countries and civil wars have plummeted.

VIOLENCE ISNT JUST WAR

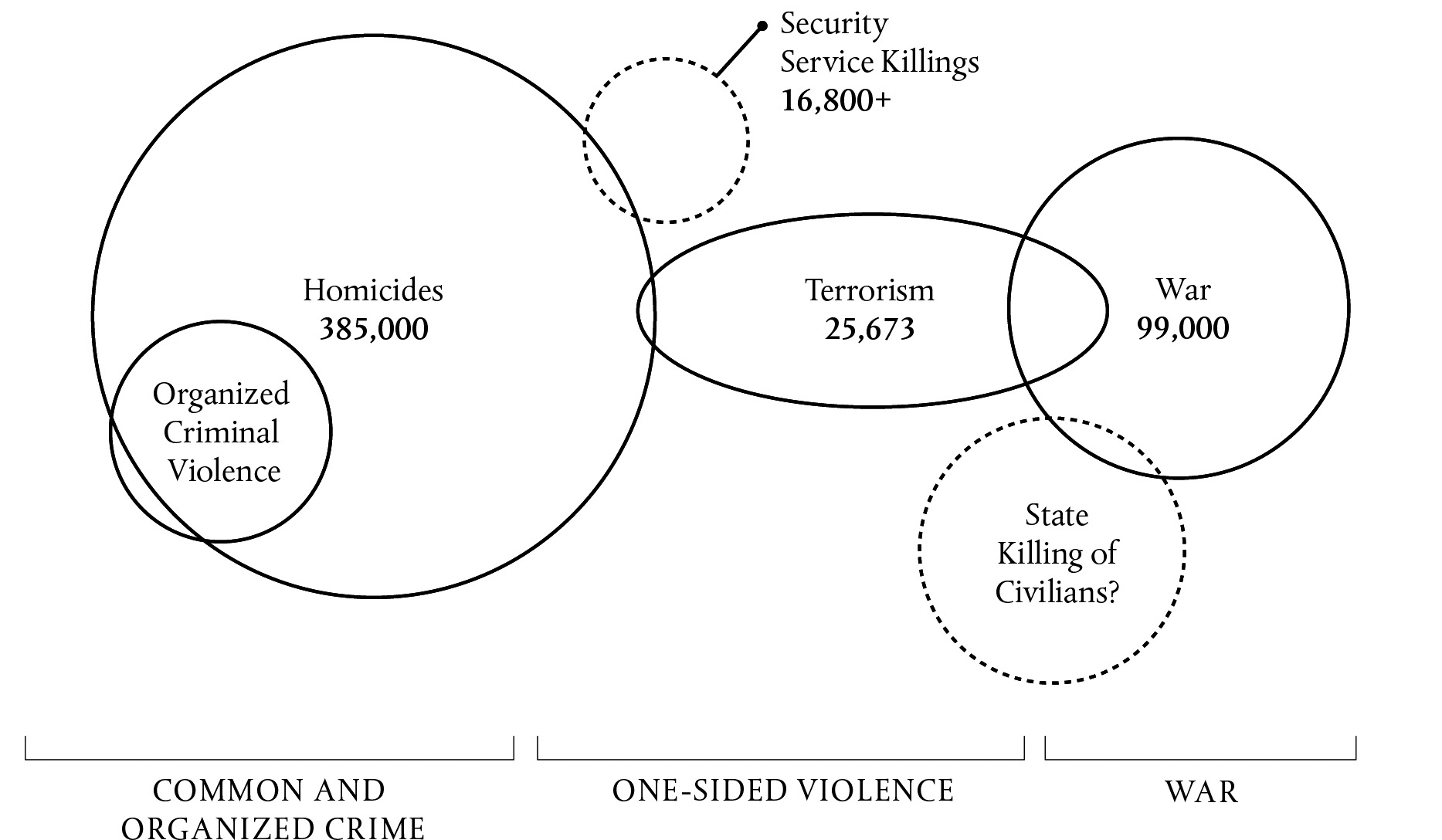

Three kinds of carnage kill four times as many people as the battle deaths in all current wars put together.

VIOLENT DEATHS IN 2016 BY CAUSE

(Dotted lines indicate severely underreported statistics.)

With a handful of exceptions, the most violent countries in the world today are not at war but are buckling under a maelstrom of gang warfare, organized crime, state brutality, and murders by paramilitaries, death squads, and ordinary people. This is the violence devastating Central America, the cocktail that has made Venezuela the most deadly country in the world. It adds to the death toll in some countries formally in conflict like Afghanistan and creates fertile soil for terrorists like ISIS. War grabs the headlines. But the security problem of our time is boiling over from countries caught in a vortex of internal violence.

Violence devastates lives and destroys countries. Its effects can last for generations. In Central America, children get recruited to join gangs or are raped by gang members starting at around age thirteen. Altered genes, of course, can be passed to future generations.

The United States has a particular interest in this problem. In 2011, New Orleanss homicide rate (the number of deaths per 100,000) was on par with the rate for all violent death in Afghanistan. The U.S. homicide rate remains four to five times higher than that of Australia, Canada, or Europe. Americans like to imagine that our gang warfare, police brutality, and inner-city predation stand apart from the problems faced by developing countries. But they are far more similar than we like to admit.

Violence feels like an intractable problem. That sense of hopelessness has altered global politics. Over half a century ago, creative leaders forged the European Union to unite a continent where two world wars had killed millions; now, the idea of European world war is unimaginable. Fifty years ago, the United States sent men to the moon. Today, we send women and children back to countries where they are being hunted by gangs.

Every country for itself, demands the new Western zeitgeist. Refugees fleeing violence, from Central America to the Middle East, are igniting political backlash on both sides of the Atlantic. In the United States, neither the more militaristic policies of President George W. Bush nor the lighter touch of Barack Obama have been able to stanch the bleeding around the globe. Indeed, both tactics poured fuel on the conflagration. Europes leaders have done no better. Crowded schools, strained public services, and fears about immigration and Islam have fueled movements to shut down borders. Britains Brexit is a nostalgic demand for a return to a little England that hasnt existed for decades. The leader of the rising Alternative for Germany party declared that border guards might need to aim their guns on illegal frontier crossers. Austrias Freedom Party, which campaigned under the slogan Austria First, is part of the governing coalition in charge of the Defense, Interior, and Foreign Ministries. It demands tighter borders just as Americas president calls for higher walls.