CUSTODIANS OF THE INTERNET

Copyright 2018 by Tarleton Gillespie.

All rights reserved.

Subject to the exception immediately following, this book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. The Author has made this work available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International Public License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/).

An online version of this work available; it can be accessed through the authors website at http://www.custodiansoftheinternet.org.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Minion type by IDS Infotech Ltd., Chandigarh, India.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017953111

ISBN 978-0-300-17313-0 (hardcover: alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

CUSTODIANS OF THE INTERNET

all platforms moderate

In the ideal world, I think that our job in terms of a moderating function would be really to be able to just turn the lights on and off and sweep the floors... but there are always the edge cases, that are gray.

personal interview, member of content policy team, YouTube

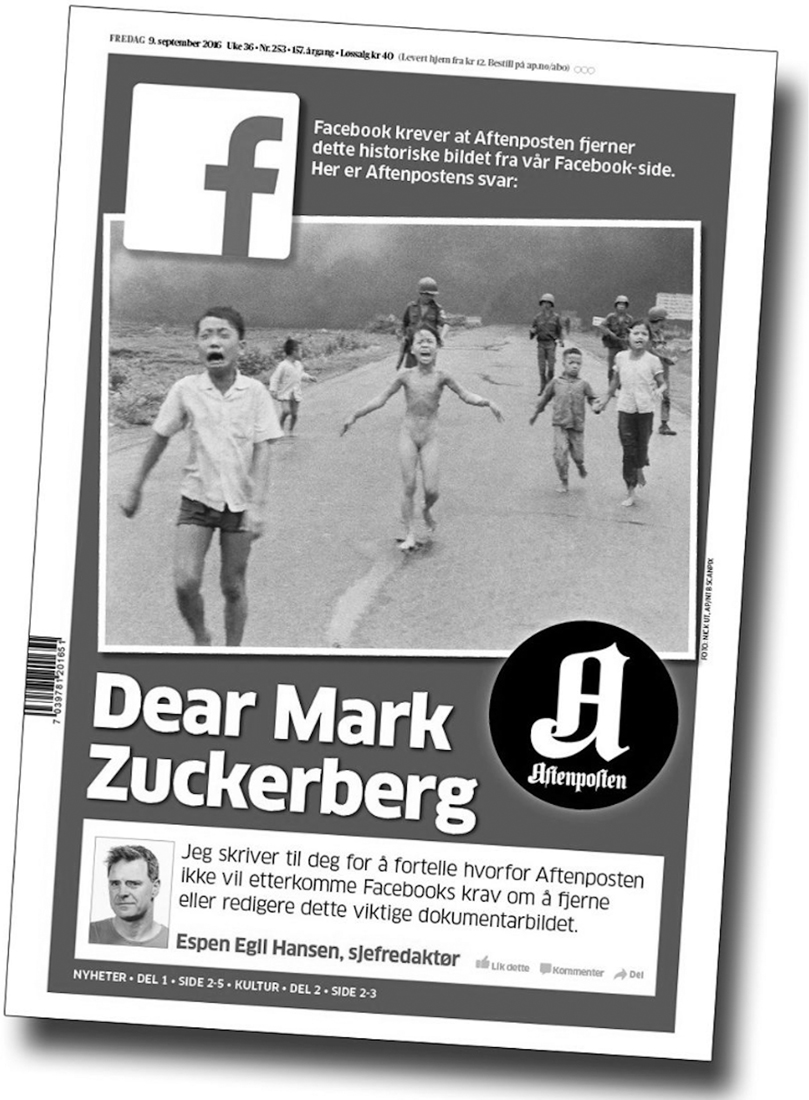

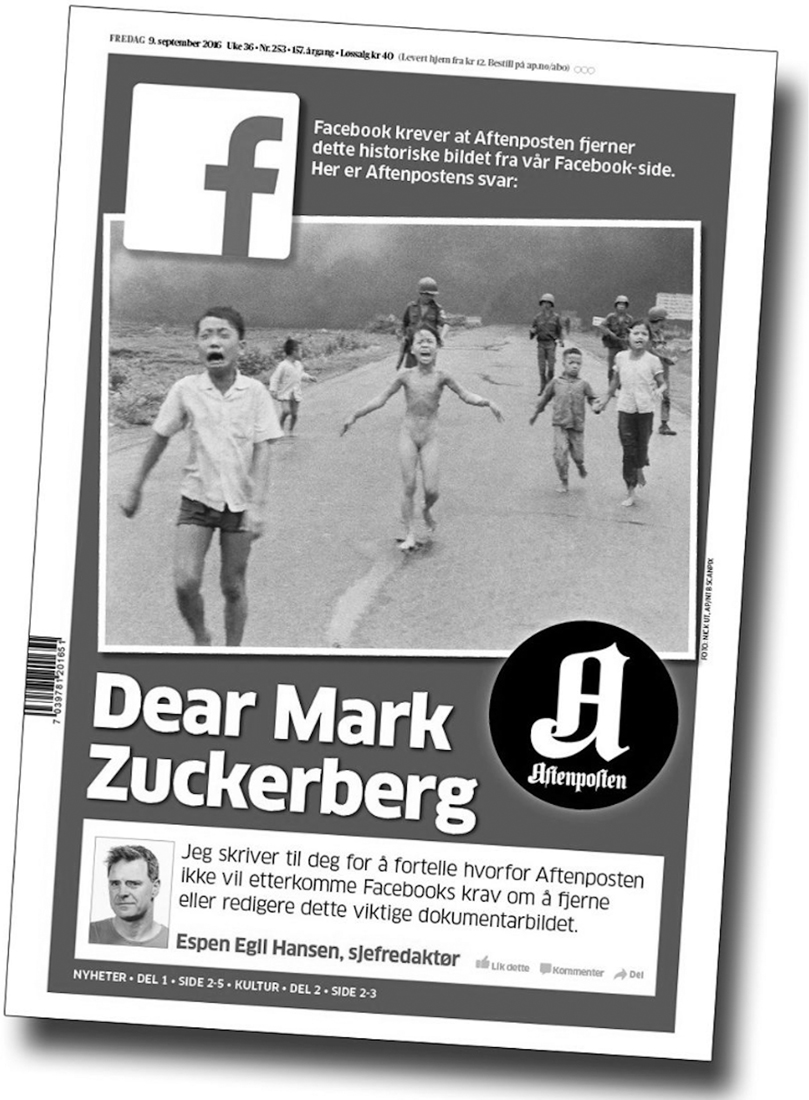

Titled The Terror of War but more commonly known as Napalm Girl, the 1972 Pulitzer Prizewinning photo by Associated Press photographer Nick Ut is perhaps the most indelible depiction of the horrors of the Vietnam War. Youve seen it. Several children run down a barren street fleeing a napalm attack, their faces in agony, followed in the distance by Vietnamese soldiers. The most prominent among them, Kim Phuc, naked, suffers from napalm burns over her back, neck, and arm. The photos status as an iconic image of war is why Norwegian journalist Tom Egeland included it in a September 2016 article reflecting on photos that changed the history of warfare. And it was undoubtedly some combination of that graphic suffering and the underage nudity that led Facebook moderators to delete Egelands post.

After reposting the image and criticizing Facebooks decision, Egeland was suspended twice, first for twenty-four hours, then for three additional days. The editor in chief of Aftenposten took to the newspapers front page to express his outrage at Facebooks decision, again publishing the photo along with a statement directed at Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg.

Front page of the Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten, September 8, 2016, including the Terror of War photograph (by Nick Ut / Associated Press) and editor in chief Espen Egil Hansens open letter to Mark Zuckerberg, critical of Facebooks removal of Uts photo. Newspaper used with permission from Aftenposten; photo used with permission from Associated Press.

More than a week after the image was first removed, after a great deal of global news coverage critical of the decision, Facebook reinstated the photo. Responding to the controversy, Facebook Vice President Justin Osofsky explained:

These decisions arent easy. In many cases, theres no clear line between an image of nudity or violence that carries global and historic significance and one that doesnt. Some images may be offensive in one part of the world and acceptable in another, and even with a clear standard, its hard to screen millions of posts on a case-by-case basis every week. Still, we can do better. In this case, we tried to strike a difficult balance between enabling expression and protecting our community and ended up making a mistake. But one of the most important things about Facebook is our ability to listen to our community and evolve, and I appreciate everyone who has helped us make things right. Well keep working to make Facebook an open platform for all ideas.

It is easy to argue, and many did, that Facebook made the wrong decision. Not only is Uts photo of great historical and emotional import, but it also has been vetted by Western culture for decades. And Facebook certainly could have handled the removals differently. At the same time, what a hard call to make! This is an immensely challenging image: a vital document of history, so troubling an indictment of humanity that many feel it must be seenand a graphic and profoundly upsetting image of a fully naked child screaming in pain. Cultural and legal prohibitions against underage nudity are firm across nearly all societies, with little room for debate. And the suffering of these children is palpable and gruesome. It is important precisely because of how Kim Phucs pain, and her nakedness, make plain the horror of chemical warfare. Its power is its violation: the photo violates one set of norms in order to activate another; propriety is set aside for a moral purpose. It is a picture that shouldnt be shown of an event that shouldnt have happened. There is no question that this image is obscenity. The question is whether it is the kind of obscenity of representation that should be kept from view, no matter how relevant, or the kind of obscenity of history that must be shown, no matter how devastating.

It is important to remember, however, that traditional media outlets also debated whether to publish this image, long before Facebook. In 1972 the Associated Press struggled with whether even to release it. As Barbie Zelizer tells it, Ut took the film back to his bureau, where he and another photographer selected eight prints to be sent over the wires, among them the shot of the napalmed children. The photo at first met internal resistance at the AP, where one editor rejected it because of the girls frontal nudity. A subsequent argument ensued in the bureau, at which point photo department head Horst Faas argued by telex with the New York office that an exception needed to be made; the two offices agreed to a compromise display by which there would be no close-up of the girl alone. Titled Accidental Napalm Attack, the image went over the wires.

Since the moment it was taken, this photo has been an especially hard case for Western print mediaand it continues to be so for social media.

PLATFORMS MUST MODERATE, WHILE ALSO DISAVOWING IT

Social media platforms arose out of the exquisite chaos of the web. Many were designed by people who were inspired by (or at least hoping to profit from) the freedom the web promised, to host and extend all that participation, expression, and social connection. Though the benefits of this may be obvious, and even seem utopian at times, the perils are also painfully apparent, more so every day: the pornographic, the obscene, the violent, the illegal, the abusive, and the hateful.

The fantasy of a truly open platform is powerful, resonating with deep, utopian notions of community and democracybut it is just that, a fantasy.

Platforms must, in some form or another, moderate: both to protect one user from another, or one group from its antagonists, and to remove the offensive, vile, or illegalas well as to present their best face to new users, to their advertisers and partners, and to the public at large.

This project, content moderation, is one that the operators of these platforms take on reluctantly. Most would prefer if either the community could police itself or, even better, users never posted objectionable content in the first place. But whether they want to or not, platforms find that they must serve as setters of norms, interpreters of laws, arbiters of taste, adjudicators of disputes, and enforcers of whatever rules they choose to establish. Having in many ways taken custody of the web, they now find themselves its custodians.

Next page