ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

At the top of my gratitude list is my familymy sister Barbara, son Brad, granddaughter Fallon, nephew Ben, cousins Bill, Bobbie, Jennifer, Em, Cholly, Sallie, Diane, Peggy, Alex, Deborah, Betty, Tommy, Tommy, Jr., and Mack. They gave me family stories and photos, hugs, a hot meal, and a good bed at the end of a long day. They listened and often urged me on. More important, they provided psychological space to discover what I would and ears that listened quietly to my tales.

Special thanks for invaluable editing advice along the way from dear friends Barbara Mowat, Suzannah Lessard, and Vincent Virga.

There are more friends, who have stuck with me through these many years, cheered me on, and reminded me of my reasons for writing this book. These include Randy Gamble, Dorothy Sauber, Kaia Svien, Bob Lyman, Margaret Veerhoff, James McCourt, Carole Look, Pat Moore, Celia Morris, Elizabeth Hagerman, Patsy Sims, Bob Cashdollar, Deanna Marquart, Alec Dubro, Kim Fellner, Noel Brennan, Alison Day, Patricia Gray, Rae Bayer, Karyn Fair, Arlene Gottfried, my 10th Street neighbors, Kevin Flood, Jimmy McCourt, my Hill Lunch bunch, Bill Turnley and family, the Coming to the Table folks, and all you out there who know who you are.

I am forever grateful to those who provided me with a peaceful room of her own: Blue Mountain Center, Lillian E. Smith Center for Creative Arts, the Apple Farm Community, Sweetapple, the Turnley cottage at Good Harbor Bay, and the Library of Congress for its generous gift of an office for many years. Heartfelt thanks to the Sapelo Foundation, which supported me with a grant in the early stages of this work.

I could not have undertaken this investigation without the resources of many archives and their staffs, including the Library of Congress, Columbus State University Archives, the Georgia Department of Archives and History, the National Archives in Washington, D.C. and East Point, Georgia, and Stacy Haralson, clerk of court in Harris County.

Many thanks to researchers Barbara Stock and Gwen Lott, editors Carole Edwards and Alice Falk, graphic designer Sally Murray James. For excellent advice along the road: Steve Bright, Bernice Reagon, Joe Hendricks, John Egerton, Randy Loney, Fitz Brundage, Rose Gladney, Woody Beck, Carolyn Karcher, Diane McWhorter, and Laura Wexler. For more wise counsel, Pamela Wilson, Bobbie Holt, Jane Bishop, Kay Koch, Sandy Geller, Bruce Heustis, and Jim Hollis.

To my incredible agent Charlotte Sheedy goes my deepest appreciation and admiration for so graciously sharing her wisdom when mine ran out and for always being there; and to my Simon & Schuster editors Malaika Adero, Peter Borland, Daniella Wexler, and Carla Benton, my sincere appreciation for making it all come together.

I wish to pay profound tribute to the many Harris County elders, the Ancient Mariners, who so graciously welcomed me onto their porches, into their parlors, and unflinchingly shared stories that had haunted them for years. To them and to my dear Edna, the black mamma who raised me up right and told me at the end that she was glad that I was different, I dedicate this book.

AFTERWORD

August 1994

I am at the Jefferson Memorial with my granddaughter, who is eight years old. We have taken turns reading all of the magnificent Thomas Jefferson quotes inscribed upon the walls. She looks at me quizzically and says, But didnt he own slaves? This is the kind of question I have dreaded ever since she was born.

We sit down on the steps and I make some stumbling explanation about how sometimes people can do things that are very wrong while, at the same time, doing other things that are quite noble. But I also tell her that he was a hypocrite. This is hard stuff for an eight-year-old, even a very bright one like her, but I know I should use the opportunity as a teaching moment: You know that you are descended from both slave-owners and slaves, dont you? I say.

She sinks into thought, and when she emerges she looks into my eyes and says, Yes, I know. But, if I ever have to choose, Ill choose the slaves. I tell her that I hope she never has to choose. And yet I realize that in writing this book, I have had to make that choice again and again. I have not relished revealing my forefathers crimes, but in order to face history squarelymy nations, my familys, and my ownI have had not so much to choose the slaves, but to choose the truth, which in many ways is the same thing. Most important, I have had to find my voice, and to choose honesty and truth over the feelings and opinions of friends and family. I have also chosen to break that ancient, ironclad rule that women must keep the family secrets. This breaking of official silences is still regarded as shameful, even monstrous, by many people, something I learned at my fiftieth high school reunion. At the dance, which was held on Confederate Memorial Day in the Confederate Naval Museum in Columbus, the band played Dixie and former classmates chided me for not standing with my hand over my heart. There I told some old friends about my book. No! some of them gasped. Surely you wouldnt!

Well, surely I have. I have done it not only for the descendants of those enslaved and otherwise victimized by my ancestors, but for men and women like me who want to know the truth of our families and our regions histories, with all of their treachery and dishonor, as well as their occasional greatness. I believe it is only with such knowledge that we and our own descendants can heal and move forward to build a nation and a world where all humans can be free.

Today, twenty years later, as I plan a retreat in the Cascade Mountains with my beautiful twenty-seven-year-old granddaughter and friend, I shudder at how close I came to rejecting her, the way so many beautiful mixed-race babies were rejected by my family in times past. I now know well the riches Id have cast aside, including my mothers loving relationship with her only great-grandchild, and my own with dozens of newfound cousins (by blood or by choice), descendants of the people my people once enslaved. Through their Williams-Hudson Family Association, which welcomed me as one of their own, and through Coming to the Table, I have found ways to rebuild and work for change. I realize, as never before, how much the white South lost when it embarked, at its dawning, upon a wicked and brutal course of rejecting and repressing not only its own flesh and blood, but all its precious black citizens.

As I bring this book to a close, America is once again aflame with racial violence and discrimination. There is no question that, as a nation, we have yet to honestly face our history and to truly embrace African Americans as full-fledged citizens and members of our human family. I believe this is the only way we can heal, as individuals and as a nation.

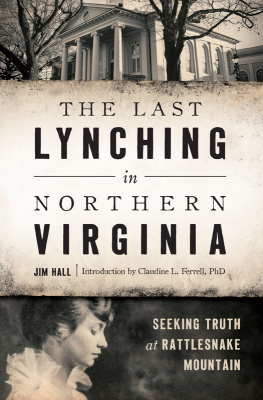

karen branan is a veteran journalist who has written for newspapers, magazines, the stage, and television for almost fifty years. Her work has appeared in Life, Mother Jones, Ms., Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, the Star Tribune (Minneapolis), the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and on PBS, CBS, ABC, CBC, BBC, and CNN.

MEET THE AUTHORS, WATCH VIDEOS AND MORE AT

SimonandSchuster.com

authors.simonandschuster.com/Karen-Branan

Facebook.com/AtriaBooks

Facebook.com/AtriaBooks

@AtriaBooks

@AtriaBooks

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexander, Adele Logan. Ambiguous Lives: Free Women of Color in Rural Georgia, 17891879. University of Arkansas Press, 2009.

Facebook.com/AtriaBooks

Facebook.com/AtriaBooks @AtriaBooks

@AtriaBooks