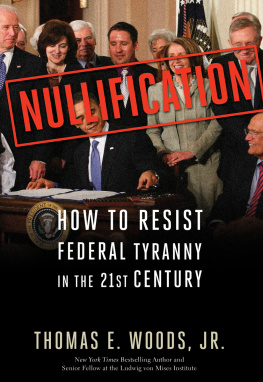

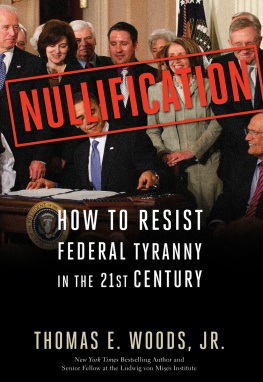

NULLIFICATION

How to Resist Federal Tyranny in the 21st Century

THOMAS E. WOODS, JR.

Copyright 2010 by Thomas E. Woods, Jr.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

Cataloging-in-Publication data on file with the Library of Congress

ISBN: 978-1-59698-639-8

Published in the United States by

Regnery Publishing, Inc.

One Massachusetts Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20001

www.regnery.com

Distributed to the trade by:

Perseus Distribution

387 Park Avenue South

New York, NY 10016

To our daughters,

Regina, Veronica, Amy, and Elizabeth

CONTENTS

I. James Madison and the Duty to Interpose:

The Virginia Resolutions of 1798

II. Virginia Informs the People:

Address of the General Assembly to the People of the Commonwealth of Virginia

III. Unconstitutional Laws Are Void:

The Kentucky Resolutions of 1798

IV. Nullification Is the Rightful Remedy:

The Kentucky Resolutions of 1799

V. The Federal Government Will Not Police Itself:

Virginia General Assembly Report of 1800

VI. The States Are the Protecting Shield:

Speech of Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull Opening of the Special Session of the Legislature

VII. We Resist:

Resolutions of the General Assembly of Connecticut

VIII. Federalism Cannot Last without Nullification:

Fort Hill Address

IX. Nullification: Why the Critics Are All Wrong:

An Exposition of the Virginia Resolutions of 1798

X. Judges Are Human Beings, Not Gods:

A Review of the Proclamation of President Jackson

XI. Nullification vs. Slavery:

Joint Resolution of the Legislature of Wisconsin

Appendix:

The Constitution of the United States

CHAPTER 1

The Return of a Forbidden Idea

WHEN HOUSE SPEAKER NANCY PELOSI was asked by a reporter in 2009 where in the Constitution she found the authority to impose a health insurance mandate on Americans, she laughed and replied, Are you serious? Are you serious? The reporter answered that indeed he was. The Speaker just shook her head, and then took another question.

Pelosis press spokesman clarified the Speakers non-answer by explaining that this was not a serious question.

Senator Pat Leahy was asked the same thingwhere in the Constitution is the federal government granted the authority to do this? His answer: Theres no question theres authority. Nobody questions that. He had no idea, in other words.

Senator Mark Warner, in turn, came out with this gem of constitutional insight: There is no place in the Constitution that talks about you ought to have the right to get a telephone, but we have made those choices as a country over the years. Got that? So what if the Constitution says nothing about granting the federal government the power to force Americans to buy approved health insurance packages? The Constitution also says nothing about allowing American citizens to buy a telephone, eat at Taco Bell, or have children, and we do those things, dont we?

The difference that managed to escape Senator Warner is that in a free society people do not require constitutional authority to act. Government does.

The controversy over health care reflects a much broader and deeper constitutional void in American life. Some fifteen years ago, a Supreme Court Justice asked the United States Solicitor General (the governments lawyer for Supreme Court cases) if he could name an activity or program that, in his view, would fall outside the bounds of what the Constitution authorized the federal government to do. He could not.

This contempt for constitutional limitations on the federal government is bipartisan and long-standing. Unsurprisingly, when the Constitution is thought of not as the strict limitation on government that its original supporters sold it as, but as something so compendiously broad as almost to defy limitation, government will continue to grow. Some federal activities have begun to alarm even those who have historically cheered government growth as a progressive force. Yet nothing has been able to stop it. Even Ronald Reagan, for all his charisma and rhetorical prowess, was able only to slow the growth of certain categories of federal spending. In 1994, the Republican Party won control of both houses of Congress in a historic off-year election victory. Government would at last be shrunk, politicians assured us.

Sure it would.

More and more Americans concerned about ongoing and apparently unstoppable government growth are beginning to wonder if some other strategy should be pursued, the exclusively electoral one having been such a failure. In the face of decades of broken promises and precious few victories against the seemingly inexorable federal advance, the pretty speeches of the plastic men are starting to ring a little hollow.

This is the spirit in which the Jeffersonian remedy of state interposition or nullification is once again being pursued. As we shall see in chapter 2, it was Thomas Jefferson, in his draft of the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, who introduced the term nullification into American political discourse. And as well see in chapter 4, Jefferson was merely building upon an existing line of political thought dating back to Virginias ratifying convention and even into the colonial period. Consequently, an idea that may strike us as radical today was well within the mainstream of Virginian political thought when Jefferson introduced it.

Nullification begins with the axiomatic point that a federal law that violates the Constitution is no law at all. It is void and of no effect. Nullification simply pushes this uncontroversial point a step further: if a law is unconstitutional and therefore void and of no effect, it is up to the states, the parties to the federal compact, to declare it so and thus refuse to enforce it. It would be foolish and vain to wait for the federal government or a branch thereof to condemn its own law. Nullification provides a shield between the people of a state and an unconstitutional law from the federal government.

The central point behind nullification is that the federal government cannot be permitted to hold a monopoly on constitutional interpretation. If the federal government has the exclusive right to judge the extent of its own powers, warned James Madison and Thomas Jefferson in 1798, it will continue to growregardless of elections, the separation of powers, and other much-touted limits on government power. A constitution is, after all, only a piece of paper. It cannot enforce itself. Checks and balances among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches, a prominent feature of the Constitution, provide little guarantee of limited government, since these three federal branches can simply unite against the independence of the states and the reserved rights of the people. That is precisely what Jefferson warned William Branch Giles was already happening in 1825: It is but too evident, that the three ruling branches of [the Federal government] are in combination to strip their colleagues, the State authorities, of the powers reserved by them, and to exercise themselves all functions foreign and domestic. Much more important than the feeble restraint of checks and balances is the ability of the states to interpose to prevent the enforcement of unconstitutional laws. That is a real check on federal power.