Where does philosophy come from? The simple answer is: everywhere! Taken literally, philosophy is nothing more (nor less) than the love (philo) of wisdom (sophia)and who doesnt love wisdom? All human societies have developed systems of knowledge to help them understand our place in the universe and to satisfy our distinctively human curiosity. Wherever you are on the globe, be it Papua New Guinea or Pasadena, there is philosophy to be found.

Sadly, as authors (and mortal beings) we are working within certain spatio-temporal constraints. Much as wed love to explore the different philosophical traditionsfrom the Akan philosophies birthed in West Africa, to Shinto thought found in ), where we briefly discuss some other philosophical traditions, and suggest further reading.

At the same time, despite the focus on the European tradition, its important to recognize that there are no pure schools of thoughtand, as a consequence of various imperial projects, the European tradition overlaps with, and blends into, a number of others. For example, Islamic philosophy from the Middle East traveled to Spain during the Islamic Golden Age. The colonial projects of the British Empire lifted and learned from the logical traditions found in India. No continent or country has a monopoly on certain forms of thought. Though weve focused on the Euro-American tradition, we have also tried to show how ideas and concepts are exchanged between, taken from, and shared among, different countries, societies, and cultures.

Big thinkers and big ideas?

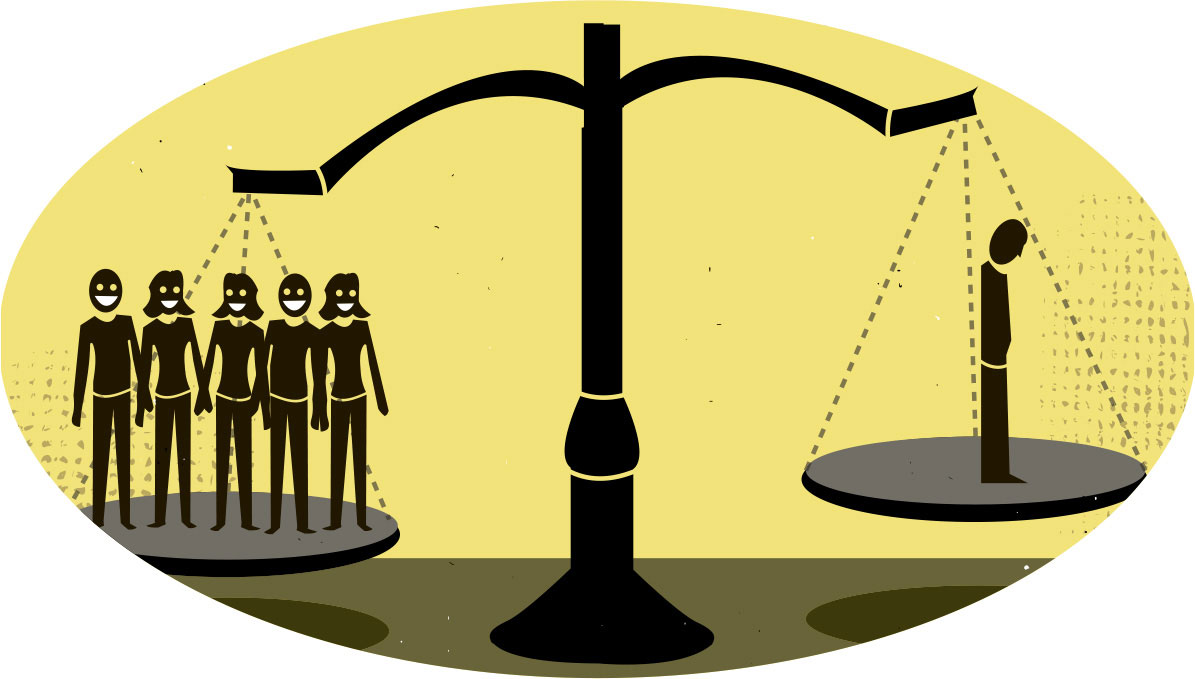

Just as no single state, country, or empire has the monopoly over thought, no single person has the monopoly over any one theory or argument. The standard histories of philosophy tend to focus on canonical figures and their big ideas. Ren Descartes, for example, is credited with the Cogito (I think, therefore I am): hes seen to be the sole creator of this supposedly groundbreaking argument. But, as many historians of early modern philosophy will tell you, Descartess work appears much less radical when situated in its proper historical contextand sole authorship becomes much less certain when we consider his discussions with fellow thinkers like Marin Mersenne and Elisabeth of Bohemia. Of course, Descartes was the one to write the ideas downin his Discourse on Method (1637) and the Meditations (1641)but does that mean that theyre his? It may interest you to know that Ibn Sina wrote down some strikingly similar thoughts in his Book of Healing (1027) a good 600 years prior, even though he is given considerably less attention in the European tradition.

In this book, were trying to resist the standard heroic genius narrative. Ideas tend to be had by lots of people in conversation. The lone figure, sat hunched at the top of their ivory tower, pulling thoughts out of the ether, is an unhelpful myth. Ideas dont spontaneously come into existence in isolation from a context. They occur in relation to other ideas, had by other people. And even when a particularly novel thinker does come along, they are (if were being honest) very rarely heroes. All the figures named in these pages have their issues. Sometimes theyre big issues. Aristotle owned slaves. Descartes performed vivisections. David Hume was racist. Frantz Fanon was sexist. There are, we think, no real philosophical heroes.

Its because of our concerns about heroes and geniuses that weve tried to emphasize the collaborative nature of philosophy, showcasing as much as we can the way that thinkers thoughts become intertwined. Simone de Beauvoir worked with Jean-Paul Sartre. Iris Murdoch with Philippa Foot. Charles W. Mills with Carole Pateman. Their work is the product of inspiration, endless discussions, back-and-forths, written and spoken. Its this discursive side of philosophy that weve tried to capture in the writing of this book, too. Its not an accident that this text is coauthored, and the books production has been a matter of talking rather than sitting in isolation, scratching a single furrowed brow (and, we hope, is all the better for it!).

Everyday philosophy

Weve split the subject up into four chapters covering four areas: society, culture, knowledge, and reality. Each of these chapters is subdivided into 13 topics, with an introduction to orient you, and some histories and timelines to give you a greater sense of the historical context of the ideas that follow. We have, throughout, tried to focus on how philosophyeven in its most abstract formintersects with everyday concerns (which is why weve started with the topic of society, rather than the supposedly grander reality). Weve also made the decision to integrate older philosophical discussions (about the nature of time, say) with newer debates (about gender essentialism)and weve tried to complement this mix with a combination of older and newer thinkers. Thats because philosophy isnt a dead disciplineits not just a long list of names in history books, or fossilized, esoteric puzzles. Its a living and breathing thing. And doing philosophy involves surprise and excitement; philosophy is about loving wisdom, not about facts or clever ideas. Philosophy is supposed to move youto happiness, to frustration, to anger, and even, perhaps, in its better moments, to joy.

How to use this book

This book distills the current body of knowledge into 52 manageable chunks, allowing you to choose whether to skim-read or delve in deeper. There are four chapters, each containing 13 topics, prefaced by a set of biographies of key philosophers and a timeline of significant milestones. An introduction to each chapter gives an overview of some of the key concepts you might need to navigate.