Table of Contents

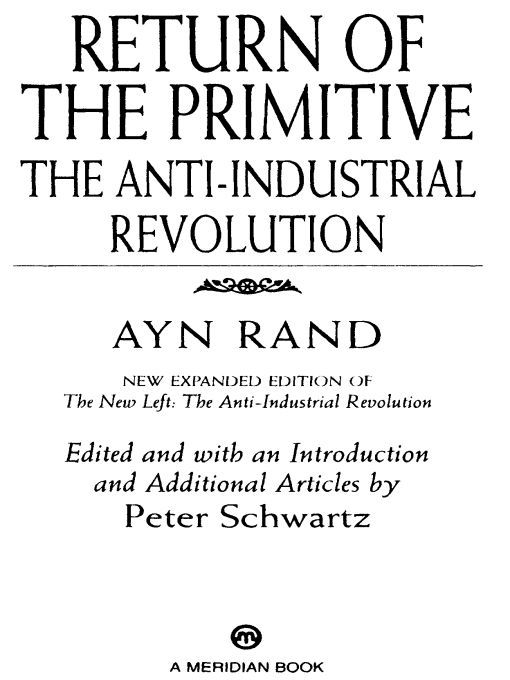

Ayn Rand was the bestselling author of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, among other enduring works of fiction. Objectivism, her unique philosophy, has gained a worldwide audience. The fundamentals of her philosophy are set forth in five nonfiction books: Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, For the New Intellectual, The Virtue of Selfishness, Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, and The Romantic Manifesto. Ayn Rand died in 1982.

Peter Schwartz has an M.A. in journalism from Syracuse University. He is the founding editor and publisher of The Intellectual Activist magazine and the author of The Battle for Laissez-faire Capitalism. He is the Chairman of the Board of the Ayn Rand Institute and is director of its writing program.

INTRODUCTION

When the original version of this book was published in 1971, it seemed that the ramparts of civilization were about to be breached. It was the time of the New Lefta time of organized violence, militant emotionalism, and open, pervasive nihilism. It was a time when college campuses were being forcibly shut down by student thugs brandishing Free Speech banners. It was a time when corporate buildings and military-recruitment offices were being invaded by guerrillas demanding Peace Now! It was a time of psychedelic flower children and peoples armies, of Timothy Leary and Abbie Hoffman and Charles Manson, of the Theater of the Absurd and the Black Panthers.

Spearheading this mindlessness was a movement that resisted definition. Its enemies were anyone and anything American, its heroes were dictatorial killers like Ho Chi Minh and Fidel Castro, its goal was indiscriminate destructionyet its leaders were hailed by cultural commentators as idealistic defenders of the individual against an oppressive state.

American society was under dizzying siege. It was in retreat, uncertain whether to embrace or repel this onslaughtan onslaught launched in the name of a cause no one could name.

Ayn Rand proceeded to name it.

In her essays in this book, she identified its ideological essence. She explained how the revolutionaries of that movement were faithful practitioners of every important idea their elders had taught them. She showed that the New Left was the offspring of the Establishments philosophers and of their anti-reason, anti-individualism, anti-capitalism doctrines.

Those doctrines were fused, in the 1960s, into an overwhelming hostility toward one distinctively Western target: industrialization. The New Left declared that the West was corrupt and that its influence had to be eliminated through the renunciation of technology. People were exhorted to give up their automobiles and shopping centers, their air conditioners and nuclear power plants.

This was the distinguishing characteristic of the New Left. It brazenly advocated what prior collectivists had been reluctant to acknowledgeeven to themselvesas inherent in their philosophy. The activists of the New Left, Ayn Rand wrote, are closer [than those of the Old Left] to revealing the truth of their motives: they do not seek to take over industrial plants, they seek to destroy technology.

While the New Left did not triumph in its anti-industrial revolution, it did pave the way for an ongoing assault on the rational mind and its products. Writing about the New Lefts campus commandos, Ayn Rand said that even though the student rebellion has not aroused much public sympathy, the most ominous aspect of the situation is the fact that it has not met any ideological opposition, that it has shown the road ahead is empty, with no intellectual barricades in sight and that the battle is to continue.

That battle is indeed continuing.

It is being waged today by two cultural movements virulently opposed to the advancesmaterial and intellectualcreated by Western civilization. One movement is environmentalism; the other, multiculturalism. Both seek to enshrine a new primitivism.

Primitive, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, means: Of or belonging to the first age, period or stage; pertaining to early times ... With respect to human development, primitivism is a pre-rational stage. It is a stage in which man lives in fearful awe of a universe he cannot understand. The primitive man does not grasp the law of causality. He does not comprehend the fact that the world is governed by natural laws and that nature can be ruled by any man who discovers those laws. To a primitive, there is only a mysterious supernatural. Sunshine, darkness, rainfall, drought, the clap of thunder, the hooting of a spotted owlall are inexplicable, portentous, and sacrosanct to him. To this non-conceptual mentality, man is metaphysically subordinate to nature, which is never to be commanded, only meekly obeyed.

This is the state of mind to which the environmentalists want us to revert.

If primitive man regards the world as unknowable, how does he decide what to believe and how to act? Since such knowledge is not innate, where does primitive man turn for guidance? To his tribe. It is membership in a collective that infuses such a person with his sole sense of identity. The tribes edicts thus become his unquestioned absolutes, and the tribes welfare becomes his fundamental value.

This is the state of mind to which the multiculturalists want us to revert. They hold that the basic unit of existence is the tribe, which they define by the crudest, most primitive, most anti-conceptual criteria (such as skin color). They consequently reject the view that the achievements of Westerni.e., individualisticcivilization represent a way of life superior to that of savage tribalism.

Both environmentalism and multiculturalism wish to destroy the values of a rational, industrial age. Both are scions of the New Left, zealously carrying on its campaign of sacrificing progress to primitivism.

It is for the purpose of analyzing the philosophic progeny of the New Left that this expanded edition of The New Left has been compiled.

I have retained everything from the original edition and added essays of my own on environmentalism, multiculturalism, and feminism. Because multiculturalists have fostered enormous confusion about the nature of racism and of ethnicity, I have also added two Ayn Rand articles on these subjectsRacism and Global Balkanizationeven though they have previously been published elsewhere (the first in The Virtue of Selfishness, the second in The Voice of Reason).

The result is a collection of essays identifying, explaining, and evaluating different manifestations of the same anti-industrial revolution.

It is eye-opening to see how much of the New Lefts once-radical agenda not only has been adopted by todays society, but is no longer even controversial. The trappings of the New Left are gone, but its substance has endured.

For example, in the 1960s there were repeated, charged confrontations between corporations and back-to-nature hippies over such matters as pollution and recycling. Now, Earth Day is an annual cultural eventpromoted by big business; now, countless products advertise themselves as ecology friendly (such as Mc-Donalds hamburgers, which the company boasts come from no cows that graze at the expense of the planets rain forests); now, the major villains in childrens cartoon programs are not criminals, but greedy tree-loggers; and now, most states, according to a news report in the