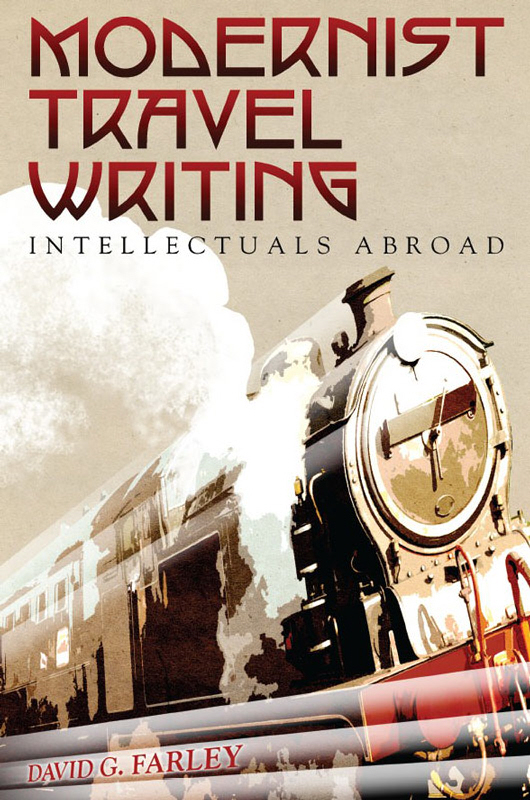

Modernist Travel Writing

INTELLECTUALS ABROAD

David G. Farley

University of Missouri Press

Columbia and London

Copyright 2010 by

The Curators of the University of Missouri

University of Missouri Press, Columbia, Missouri 65201

Printed and bound in the United States of America

All rights reserved

5 4 3 2 1 14 13 12 11 10

Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8262-1901-5

ISBN 978-0-8262-7228-7 (electronic)

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

Design and composition: Stephanie Foley

Printing and binding: Integrated Book Technology, Inc.

Typeface: Goudy

To Johanna, for making travel such a delight these many years

And to Lucy

Contents

Acknowledgments

TRAVELING WITHOUT GUIDES IS FOR THE ADVENTUROUS AND the intrepid, among whom I do not count myself. I would like to thank two of the most outstanding guides I could have hoped for as I set out, Holly Laird and Robert Spoo. They shaped this project in particular and my own outlook on modernist literature in general in more ways than I can say. I am forever indebted to them. Johanna Dehler has read the manuscript through many times over the years as it has grown and transformed and has always helped me to sharpen my ideas and my presentation. I would also like to thank my family for the dinner-table conversations from which, in some obscure way, this project grew. A special thanks to my sister Margaret Farley for her expertise and for fielding many a random phonecall.

At the University of Missouri Press, I would like to thank Clair Wilcox for his sage advice and tremendous patience in ushering this project along. Thanks as well to John Brenner and Sara Davis and to Tim Fox for his careful eye. I would also like to thank the anonymous readers for their thorough reading of the manuscript and encouraging feedback. Their comments resulted in me clarifying my argument at several key points. Any lingering errors are of course my own.

I would also like to thank the following people and institutions: The National Portrait Gallery, London, for permission to reproduce Wyndham Lewiss drawing of the head of Rebecca West; Lisa Aguilar at the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin for permission to reproduce the map of Morocco from their collection; Omar Pound for first making available to me a copy of Ezra Pounds 1921 passport and The Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, for the reproduction; Ezra Pounds passport is reproduced with permission of New Directions, agents for the heirs of Ezra Pound; Lori Curtis, formerly of the University of Tulsa McFarlin Library Special Collections, for her help in navigating the Rebecca West Collection; Neelam Mughal, whose feedback and advice was of enormous help at a crucial stage of this project; I would also like to thank my colleagues at the Staten Island campus of St Johns University, especially Harry Denny and Connie DeSimone, for their patience, advice, and help in big ways and small.

Finally, to the many guides I have had over the years, looking back, and considering, I feel it fitting to say with thanks.

Modernist Travel Writing

Introduction

TRAVERSING THE SPACE BETWEEN

History? How can you get history in the making, on the spot, as it happens? There were several histories all going on together, unconnected, often contradictory narratives that met and crossed, andthey were all history.

Lincoln Steffens, Autobiography

Somehow the furthest parts of the world have the finest things in them.

Herodotus, The History

TRAVEL AND TRAVEL WRITING TRANSFORMED LITERARY MODERNISM as surely as they were transformed by it. The fragmented forms, montage techniques, and streams of consciousness that are the salient and distinguishing features of modernist style and experimentation owe much to the foreign scenes, exotic locales, wrenching perspectives, and uncanny displacements that were the result of a generation unmoored from convention and enlivened by foreign travel. Those modernist writers in particular who were forged in the smithy of the London vortexthat concentrated energy that drew together writers and artists in the early years of modernisms flourishingwere influenced as much by dispersal as by concentration, by real and foreign landscapes as much as by the surreal inner landscape of the subconscious or by any group dynamic. We need only to recall the itinerary of cities in T. S. Eliots The Waste Land, the place names and foreign languages that punctuate Pounds Cantos, or the foreign terrains and transgressed boundaries of Virginia Woolfs Orlando to get a sense of the importance that travel had on the creative consciousness of the period.

At the same time, however, it is important to distinguish between modernist works that employed the vocabulary of travel indirectly through the citation of foreign literary works and traditions (the internationalism of modernism remains one of its most distinguishing features) and works that drew directly on the experience of foreign travel. Thus, for example, Eliot did not journey to Jerusalem, Alexandria, or Carthage to gather material for his poem, nor need he have done so in order for these foreign cities to function as the signposts of civilization or the coordinates of culture pointing to contemporary desuetude. Nor do we as readers feel that by visiting these cities, or the sites on which they stood, the notorious difficulties of The Waste Land would be dispelled or the fragmentary nature of the poem suddenly coalesce into meaning. On the contrary, Eliots poem maps a distinctly literary and cultural terrain, and to assist readers in navigating this terrain, he appended footnotes that point to literary sources, suggesting that his poem is firmly grounded in textual signifiers, not in geographical locales.

We likewise need to draw a distinction as Helen Carr has recently done in her survey of the voluminous and varied body of travel writing that appeared between World War I and World War II, between travelling writers and actual travel writers. While many scholars have noted how traveling itself became a much more common, almost obligatory, activity for a generation of writers freed by the advances in transportation technologies, the modernist features of travel writing during this period are much harder to see. In Carrs view, the increased tendency for the present day travel book to draw as much on a fragmentary interiority as on an objective reality, had its origin during the modern period: In the twentieth century [the travel book] has become a more subjective form, more memoir than manual, and often an alternative form of writing for novelists (74). More than an alternative form of writing, the travel book became an important genre in the hands of certain modernist writers, and Carr helps us see the ways in which modernism and the travel genre intersect in important ways, an intersection that needs to be examined more closely.

In Modernist Travel Writing, I likewise examine the particular features of the travel genre through the modern periodthe thirties especially, but also in the years around World War Iin the travel writing of four authors who were variously associated with literary modernism, the movement that emerged in the early years of the twentieth century. I first discussas a kind of preamble, but also as a way of addressing critical genealogies of modernismEzra Pounds views on modern travel, and I examine the one travel book he wrote

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.