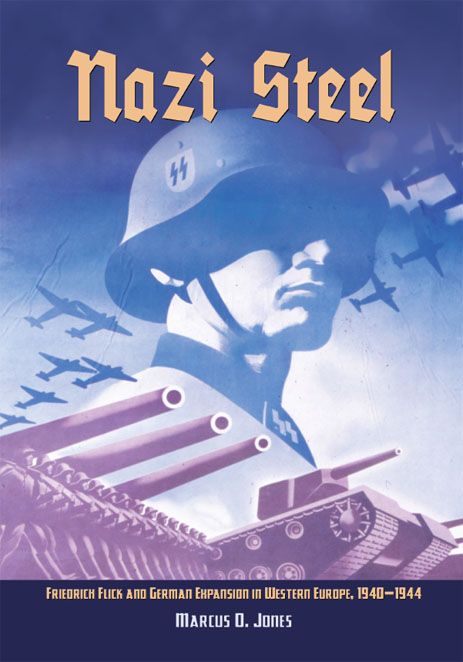

Nazi Steel

FRIEDRICH FLICK AND GERMAN EXPANSION

IN WESTERN EUROPE, 19401944

MARCUS O. JONES

NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS

ANNAPOLIS, MARYLAND

NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2012 by Marcus O. Jones

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jones, Marcus O.

Nazi steel: Friedrich Flick and German expansion in Western Europe, 19401944 / Marcus O. Jones.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61251-095-8 (e-book) 1. Flick, Friedrich, 18831972. 2. Flick, Friedrich, 18831972Political activity. 3. IndustrialistsGermanyBiography. 4. Steel industry and tradePolitical aspectsGermanyHistory20th century. 5. World War, 19391945Economic aspectsGermany. 6. GermanyEconomic policy19331945. 7. Steel-worksFranceLorraineHistory20th century. 8. World War, 19391945Economic aspectsFranceLorraine. 9. World War, 19391945Occupied territories. 10. GermanyTerritorial expansionHistory20th century. I. Title.

HC282.5.F54J66 2012

338.7669142092dc23

2011047972

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

Book layout and composition: Alcorn Publication Design

CONTENTS

T his study explores an exemplary instance of the close interaction between private and official interests in planning and executing the programs of the Nazi government, namely the acquisition in 1941 of the Rombach steel works by the German industrialist Friedrich Flick. The industrial concern headed by Flick was among the largest and most influential steel producers and manufacturers of war materil in the German economy during World War II. Its activities in the occupied territories of Western Europe centered on control of the Rombach works, a large operation established in Lorraine in the late nineteenth century by German industrialists and expropriated by France, along with the entire region, in the aftermath of World War I. After successful military operations against France in 1940, the Nazi regime actively sought the collusion of the German industrial community in mobilizing the productive capacity of occupied territories for the war effort, and numerous private German businessmen advanced claims on the lucrative assets in Lorraine and adjacent regions. In his bid to gain control of the Rombach works, Flick was successful for reasons specific to his position within the Nazi German economic system and the character of his interests. This account of his activities, then, serves as a fine example of Nazi economic and occupation policy and its response to party, business, and bureaucratic influences.

Flicks campaign to gain the wartime trusteeship of the Rombach works suggests much about the relationship between the German industrial community and the Nazi regime, and their joint role in expropriating and using the industrial assets of occupied Europe. Prior historical research provides general points of departure for a survey of that relationship, having demonstrated that the Nazi regime could count on a substantial convergence of opinion among the leading members of Germanys traditional conservative elites, especially about the desirability of a European continent

That broad consensus should not obscure the differences that separated many industrialists from the regime over the form that incorporation of foreign assets should assume. Within the parameters established by the regime, there remained discretionary space for the largest German industrialists to define and pursue their interests in competition with one another and, to a certain extent, with the regime. The specific scope and character of that space in the case of an industrialist like Flick and the way he functioned within it have become more accessible to historical analysis with the end of the Cold War and the opening of new archives. With the reversal in Germanys strategic fortunes after 1942, the heightened production requirements of an intensified war effort ruled out the further pursuit of radical occupation measures to recast the shape of Europe. According to Milward, Nazi conceptions of European economic organization therefore were never realized.

There are two primary objections to the foregoing understanding of Nazi economic policies in occupied Europe. The first deals with the larger productive framework within which occupation policy was cast. Research on the German economy over the past three decades has demonstrated that the initial phase of partial mobilization, stretching from 1936 (at the earliest) or 1940 (at the latest) to early 1942, was less a component of a Detailed analyses of Nazi labor policy and public finance, civilian consumption and spending, and war output suggest that the Nazi regime anticipated and planned for a long war in 193839. The regime introduced the most important real and percentage increases in taxation and armaments spending in the opening years of the war, and considerable redirection of consumer industries toward military purposes accompanied an effort to organize the labor force, especially women, to an extent far greater than historians long appreciated. The profusion of self-duplicating military, civilian, and party agencies characteristic of the Nazi regime was more of an obstacle than stimulus to the efficient organization of the economy. Therefore, the stagnation of output in the early stages of the war detailed in the postwar United States Strategic Bombing Survey, the findings of which constitute the basis of most assessments of German economic performance, resulted not from a considered strategy but from mismanagement of the war economy on a massive scale.

The second objection deals with the presumptive link between the ideological predispositions of the authorities and the policy outcomes pursued. Many of the economic measures cited by historians as characteristically National Socialist need not necessarily have derived from Nazi economic ideas, such as they were.

This is not to suggest that the Nazi regime pursued an agenda, however well or poorly, akin to those of other nation-states in wartime. Rather, in considering Nazi plans and policies one must be mindful of a key characteristic of the regime, namely the extent to which it succeeded in harnessing apparently rational means to the pursuit of murderously irrational ends. Thus, some historians have interpreted the proliferation of Nazi economic offices and authorities, which in many cases gave party hacks priority over technical functionaries, more as a makeshift for maintaining the dictatorship than a program of radical economic organization. In other words, certain features of the Nazi economic program in the occupied West appear consistent with the predictable imperatives of wartime mobilization, whereas others, such as the wholesale deportation or extermination of ethnic minorities, were clearly not. In the absence of an integrated history of German economic and occupation policy in Western Europe, therefore, overarching reliance on the idea of a distinctive Nazi New Order to account for economic policy seems questionable.

Basic to the economic potential of the Nazi regime to carry out its program of conquest and exploitation in Europe was the German corporate community, which even in late 1939 owned and managed the overwhelming bulk of German production. Without the collusion of German managers and private businessmen, the Nazi regime stood no chance of providing successfully for a war to secure vast new areas for a future German empire and reshape the ethnic face of Europe through what one prominent historian has referred to as a demographic revolution.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).