Copyright Chandran Nair, 2011

The right of Chandran Nair to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2011 by

Infinite Ideas Limited

36 St Giles

Oxford, OX1 3LD

United Kingdom

www.infideas.com

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of small passages for the purposes of criticism or review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. Requests to the publisher should be addressed to the Permissions Department, The Infinite Ideas Company Limited, 36 St Giles, Oxford OX1 3LD, UK, or faxed to +44 (0) 1865 514777.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-906821-49-4

Brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners.

Designed and typeset by Cylinder

Printed and bound in Singapore

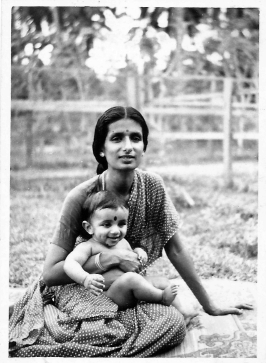

To Sumathi Letchimy Narayanan and Kadangot Parameswaran Nair

[World] population is projected to rise from 6.7 billion to 9 billion between now and 2050, and more and more of those people will want to live like Americans.

Thomas L. Friedman

S ome twenty years ago, I found myself speaking more and more at a range of business and other forums on what I loosely called environmental issues. A recurring theme was the links between these issues and a range of social, economic and political challenges. Over time, I became increasingly preoccupied by what would happen if Asia continued to develop along Western lines in particular, if countries across this huge and disparate region were to adopt consumption-driven capitalism as both their goal and their means of reaching that goal.

Often I found myself tempering my opinions, worried I would be accused of being unqualified or poorly informed on many of the issues I addressed. But as the speaking opportunities continued to arrive, I found myself testing more of my half-baked ideas to see how they were received.

I discovered that some parts of my audiences, notably business leaders and policy makers, often looked uncomfortable with my suggestion that the current trajectory was unsustainable. But there were others who were broadly receptive, even if the more supportive comments were often made privately after a meeting had ended.

I was curious. Who were the Brahmins deciding what topics were acceptable, which views could be expressed? Could I speak out more?

Certainly, the opportunities to do so increased, as more and more forums began including an obligatory session sometimes an entire event on topics familiar to me, the ones I had spent years working on as a CEO and environmental consultant managing projects across Asia, from China and India to Indonesia, Thailand and Vietnam.

Despite sparing no effort to avoid offence by being as polite and courteous as possible, I often found myself accused of being unwarrantedly negative and pessimistic the last a charge I found difficult to accept, having long regarded myself as an incorrigible optimist.

At one forum in Sweden, a senior United Nations official told me, albeit in a friendly manner, that I was a demagogue. I sensed that while he agreed with much of what I said, like many UN officials, he was worried that I had breached some unspoken protocol by throwing out a challenge to the business leaders, politicians, academics and others in the audience.

At another meeting, a regional economic summit in Hong Kong in the mid 1990s, I was clearly the token environmentalist. I spoke about the dramatic deterioration of air quality in the Greater Pearl River Delta region, and questioned the conventional view that investment and growth would lead to a prosperity that, in turn and more or less automatically, would create the conditions for the environment to improve. I was told that my concerns about the environment were laudable but my fears were overblown; I should not worry as it would never get that bad, and before it did, business would respond.

Fifteen years on, the pollution in Hong Kong and its neighbour, Guangdong, has worsened, and conference themes have expanded in scope from how to be a better environmental citizen and green your operations to addressing global climate change and sustainability.

A talk in the United States in 2008 drew a different response. Even though the audience was a largely liberal crowd more Oprah/Obama than Sarah Palin/Tea Party my suggestion that if Americans were serious about global warming then they might think about taking some action at home was not well received. Clearly, even floating the idea that consumption could be tempered perhaps by restricting car ownership to one vehicle per household, introducing a carbon tax or possibly even eating less was tantamount to foreign interference in US internal affairs.

Nonetheless, as climate change moved up the political agenda and into the mainstream, I found myself encountering less direct rejection of what I had to say. The calls for corporate social responsibility increased, and more and more forums made room for inspirational speakers calling on their audiences to become more responsible eco-citizens and be the change (watch the TED talks). Leadership remained in, but only if it took note of new social networks that were mobilizing citizens to take action. Sustainable solutions replaced innovative ones, consumers became ethical, and companies were urged to reduce their environmental footprints because going green meant saving money simultaneously benefiting the world, their customers, themselves and their shareholders.

At least, however, the issues were being raised. And slowly far too slowly attitudes began to alter. In June 2009, speaking in Bali to a group of clients of one of the worlds oldest private wealth banks, I outlined the conundrum that consumption-led growth posed for Asia. I was surprised at the level of interest I generated. Several even accepted my throwaway lines that bling is out, less is more and that constraints had to be put on consumption. In the audience was the CEO of a leading global publisher. I had expected to be dining alone, but instead I ended up hearing him suggest that I should expand and write down what I was saying. What you are reading is the result of our conversation.

Neither East nor West

The form of this book took a while to emerge. At its heart lies a discussion about the re-emergence of Asia as an economic power, and the dilemma this poses to itself and the world. But as I shared tentative outlines with a few friends, I was often told to make sure what I said could not be attacked or dismissed as an anti-West rant.

These warnings troubled me. Why was it that these people liked the idea of having me air my views, but believed they should warn me about the likely reaction from the elite inhabitants of the well of conventional wisdom? Would it really be so dangerous to draw attention to what was clearly visible not just to me but to any reasonable being? After all, every day of the week it is possible to find articles and op-ed pieces in the international press critical of China and India, and it would not take long to find other articles criticizing the way in which every other country in the region is run.

Next page