C ontemporary foreign affairs are generally being studied as anything but grand, focusing on individual cases in a fragmented process that has challenged the capacities for comprehensive analysis.

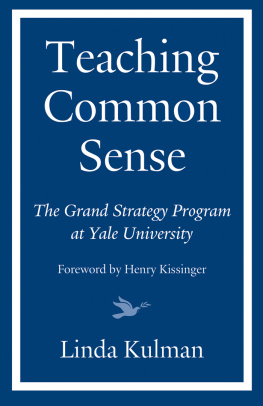

The program in Grand Strategy at Yale University seeks to overcome this problem by conveying to future leaders todays college, graduate, and professional studentsboth an intellectual understanding of and some operational experience in strategy and policy in a comprehensive structure for international relations. Regarding the importance of such analysis, I wrote long ago, History is not a cookbook offering pretested recipes. It teaches by analogy, not by maxims. It can illuminate the consequence of actions in comparable situations, yet each generation must discover for itself what situations are in fact comparable. No academic discipline can take from our shoulders the burden of difficult choices. In the past decade and a half, I have observed and engaged with the faculty and students in the Grand Strategy program at regular intervals and have seen the seminar not only achieve the objectives of its founders by instructing students in history, strategy, and decision making, but also emerge as a model for educational emulation and a symbol for intellectual innovation elsewhere.

Today, in pursuit of objectivity, the study of history is shying away from policy recommendations, while schools of policy studies, in pursuit of theoretical rigor, are avoiding historical cases. This gap is what the Grand Strategy program knows it must learn to close. The programs challenge is to expand each generations fund of experience without becoming overwhelmed. Thus, it begins with the classics, distillations of experiences presented to be applicable to futures beyond imaginationan inherently evolving canon of works that from Sun Tzu to Thucydides to our own time has provided intellectual inspiration and shaped political institutions and practices. The greatest challenges to strategy and statecraft lie in the realm of unavoidable uncertainty, where decisions must be made before it is possible to know all the facts or to assess their ramifications. An education in the classics offers a leader a body of knowledge which can help prepare him or her for the necessity of taking action in moments of daunting uncertainty, including on matters critical to world order. In this sense, the Grand Strategy program has revived and reemployed a humanistic culture of learning and decision making that was once understood to be fundamental, yet in more recent times has largely been neglected.

I am proud to have been associated with this pioneering effort since its inceptionwith those who brought the idea into being: Paul Kennedy, John Lewis Gaddis, and Charlie Hill; those who have made the continued existence of the program possible: Charlie Johnson and Nick Brady; the two Yale presidents who have supported it: Richard Levin and Peter Salovey; and most recently, the new director of the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy, professor and master of Branford College Elizabeth Bradley. The efforts of these and other individuals are comprehensively described in this book. Not only has Linda Kulman chronicled the history of the program, she also has captured the learning that I have seen occur around the Grand Strategy seminar table when lively teachers, eager students, and great ideas converge. This book demonstrates how the programs approach, essential to our future, has both come into being and evolved.

Henry Kissinger

February, 2016

T his history is based on reporting and research that I conducted intermittently over four years. From 2011 to 2015 I had an all-access pass to Grand Strategy seminars, crisis simulations, and class dinners, and the extraordinary cooperation of the professors and students, many of whom I spoke with more than once. I was also fortunate to interview Nicholas Brady, Charles Johnson, Henry Kissinger, Richard Levin, Peter Salovey, George Shultz, and Yale professors Scott Boorman, David Brooks, John Negroponte, Douglas Rae, Gaddis Smith, and Norma Thompson. Among the former program administrators with whom I spoke were Ted Bromund, Jeremy Friedman, and Caroline Lombardo.

Since the grand strategy of the Brady-Johnson Program in Grand Strategy is not to shape current policy but to train future decision makers, this history presents the results of a groundbreaking survey of 385 alumni enrolled in the class between 2000 and 2014, with the aim of seeing the programs long-term impact. Comments from former students make it clear that the professors achieved their goals, and Id like to thank all of the participants for sharing their views.

Im particularly grateful to the programs three founding professors, John Gaddis, Charlie Hill, and Paul Kennedy, for entrusting me with this project, to Elizabeth Bradley for her inclusiveness and for enabling me to view Grand Strategy as a set of leadership principles, and to Sam Chauncey and Paul Solman for their insights and friendship. The help I received from Igor Biryukov, Kathleen Galo, and Elizabeth Vastakis was invaluable, with deepest thanks to Sara Rutkowski. Among former students, Id like to single out Conor Crawford, Campbell Schnebly- Swanson, Justin Schuster, Isaac Wasserman, and Haibo Zhao, who were as generous as they are impressive. Chris Howell lent moral support to this project from day one, and later, his senior thesis on the intellectual history of grand strategy. Colonel Craig Wonson, the first Marine Corps fellow assigned to International Security Studies to provide a military perspective on grand strategy, graciously did the same for me.

Soon after I began reconstructing the programs history, I met with Paul Kennedy at Yorkside Pizza, a basic but venerable restaurant down the block from the universitys Hall of Graduate Studies, where the Grand Strategy seminar usually meets. I popped open my laptop on the table between us as he began to describe what led the three professors to create the program. Bring a tape recorder the next time we meet, Kennedy said. While youre typing, you might miss a point Im making.

As a journalist I had long ago concluded that taping interviews hindered rather than helped me in my reporting. I didnt pay as much attention to what was being said in the moment in the belief that I could go back and listen again. But too often the recorder malfunctioned, and even when it worked, I found most of what I didnt catch the first time of marginal value.

I did, however, tape my next conversation with Kennedy. Several months passed before I had an epiphany about why hed insisted upon it. It happened one fall evening on the train from New Haven to Washington. Earlier that day Gaddis had moderated the Surprise and Intelligence class, a fall staple that focused on the decade-plus period between the fall of the Berlin Wall and 9/11, two unforeseen events that altered the world. The message had been to pay attention to everything. Kennedy, at Yorkside, had been giving me a subtle lesson on how the human mind worksactually a primer on Grand Strategy. He was telling me how difficult it is to process all of the information that comes at us.

When Nick Brady and Charlie Johnson, who endowed the Grand Strategy program and after whom it is now named, commissioned me to write this intellectual history in 2011, the question at the heart of my reporting was, how is critical thinking taught? The plan was for me to attend the Monday-afternoon seminar for a full year to capture the spontaneity, drama, and learning that occur in the GS classrooms and as many extracurricular presentations and dinners as practicable. I would also conduct interviews with the professors and current and former students. The final product, as Gaddis described it, was to be a narrative rendered with a novelists eye. Ive used pseudonyms when I quote students in class unless permission was otherwise given, but the people are real and the other details about them have not been changed. If they agreed to be interviewed, I used their real names, except where specified, and quotations from these conversations and the classes that I attended are from my notes.