SOMINI SENGUPTA

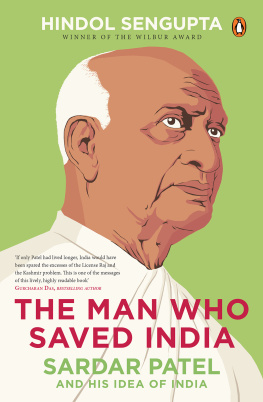

The End of Karma

HOPE AND FURY

AMONG INDIAS YOUNG

W. W. Norton & Company / New York / London

Independent Publishers Since 1923

For my daughter, with love and thanks

Nervy, glowering, your daughter

wipes the teaspoons, grows another way.

ADRIENNE RICH,

Snapshots of a Daughter-in-Law

The center was not holding.... Adolescents drifted from city to torn city, sloughing off both the past and future as snakes shed their skins, children who were never taught and would never now learn the games that had held the society together.

JOAN DIDION,

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

The End of Karma

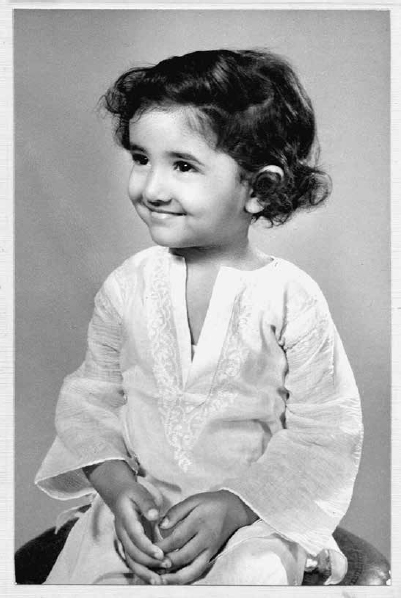

Author as a child in India.

B y the time I turn eight, with a cake from Flurys ptisserie on Park Street, my parents have hawked some wedding gold, hustled for passports, and procured three plane tickets out of Calcutta.

It is September 1975, steamy monsoon, when rain clouds break late in the day and democracy comes to a grinding halt. By now, our prime minister, Indira Gandhi, has declared a state of emergency for the first time in the history of independent India, which means that newspapers arrive some mornings with an empty front page, dissidents go to jail, and the men of the slums are enlisted in an aggressive government-sponsored birth control program. In exchange for vasectomies, they are sometimes offered a patch of urban slum. Sterilization becomes the most potent symbol of Mrs. Gandhis emergency ruleand the closest our country comes to totalitarianism.

The emergency forms the backdrop for our move. My parents decision to leave is material, not political. By this time, inflation has hit 30 percent. Refugees from the war over East Pakistan crowd into our city, erecting vast shanties of tin and tarp across from my grandmothers house. Every day come new corruption scandals about politicians and civil servants. Strikes shut down Calcutta.

My parents are not among the countrys deprived. Baba is a midlevel civil servant. Ma teaches math. They make enough to rent a two-room flat of our own, but not enough to splurge at Mocambo as often as they would like. They can pay for my piano lessons, but theyre not posh enough to become members of the Calcutta Club.

Their frustrations are the frustrations of what is, in 1975, a tiny urban middle class. Baba gets tired of hustling for a tank of cooking gas. He scours the city for Horlicks, the malted milk powder that is supposed to fortify a skinny, sickly child like me, but which becomes more and more scarce as inflation rises and traders start hoarding. He can rarely afford a pack of Rothmans, his preferred smoke. One night, walking home along Deshapriya Park, he steps over the corpse of a rickshaw puller whom local thugs call a police informant. Calcutta, that steamy metropolis of Victoria and jazz, is fast becoming what a future prime minister would call a dying city.

I imagine Baba and Ma whispering to each other in the dark, while I sleep: Is this what you call home?

My parents want more. They want out.

And so, late one night, long past my bedtime, the three of us board a whirring, air-conditioned British Airways jet, waving and waving to an army of relatives who remain behind. My parents are allowed to bring with them the princely sum of eight U.S. dollars each, thanks to Indian banking regulations at the time.

My parents dont know how they will make it so far from home. They know only that they will not make the more conventional journey to Britain. Baba is convinced that Indians clean other peoples toilets in Britain, which is his way of saying that they do dirty, dehumanizing workthat they are, in effect, untouchables. We will not clean toilets, Baba insists. We will go to the New World. I have no idea why he believes Indians dont clean other peoples toilets in the New World. But he does, which is why we opt to freeze to death instead.

We land first in a town called Selkirk in the flat cold middle of Canada, where my uncle, my fathers older brother, has come before us. We squeeze into his familys apartment, which is across the road from a mental asylum. Only a field of snow separates the hubris on our side from the madness on theirs.

Every year, Ma, Baba, and I pack up and move. We settle into a different apartment, a different school, a different city, until, eventually, we pack up our autumn gold 76 Ford LTD and drive southward across the continent. We stop in Minneapolis, Salt Lake City, the Petrified Forest, Las Vegas. Motel after motel after motel. What are we chasing? I dont have the courage to ask. I am told only that there are palm trees in California and friends from Calcutta.

In my memory, my parents are unmoored and happy. They have a new baby, my sister, daughter of the New World.

East of Los Angeles, on the banks of rushing Interstate 10, we buy a house in a suburb of strivers. Our street is lined with identical L-shaped houses with jutting-out double garages, sloped roofs, oak trees out front. We have avocado green wall-to-wall carpeting and a calla lily that someone before us has planted by the door. Our neighbors are secretaries and schoolteacherswhites mostly, some Chicanos, a handful of Japanese-Americans who never speak publicly of the internment during the Second World War. We are the only Indians for miles. And so the questions thrown at me are banalnothing terrible, just foolish.

Do you eat monkey brain?

Hey, Gandhi!

Whats that red dot mean?

Et cetera.

Daughter of the Old World, I tell myself to keep my eyes on the road ahead. Draw a thick velvet curtain over memory. Dillydally, look back, and youre likely to stumble and fall.

This is good guidance, except that nearly every other summer, during school holidays, I am ferried back to Calcutta to commune with the past. I no longer know how to respond when a barefoot child on Park Street tugs at my American clothes, wanting coins. I cringe when Ma bargains with the hollow, barefoot rickshaw pullers. When the electricity goes out, which it does every day, because theres a shortage of power, the ceiling fans stop rasping and the air gets choking hot. What I would have known how to handle, had I grown up there, I no longer know how to handle. As I get older, the Indian oddities are joined by prohibitions: Dont go to the park by yourself. Dont wear shorts. Dont open the fridge when menstruating. Dont touch the untouchable. There are so many rules, more because Im a girl. They are stultifying. They make me want to run back home.

Except that coming home to California is also awkward. How do I explain a summer in the City of Dreadful Night to friends who have spent their holiday listening to Olivia Newton-John?

This toing and froing, this explaining to one side and then the other, demands considerable dexterityand occasionally fibs. When Mrs. Gandhi lifts the state of emergency in 1977, only to be ousted in the elections that follow, her political rival and successor, Morarji Desai, appears on 60 Minutes to extol the virtues of drinking his own urine. It is ancient Vedic practice, he says on prime-time American television. The next morning, I feign a bellyache and skip school. Indians drink their own pee? This is not a question I want to deal with during recess.

Perhaps this is when my parents question starts to become mine: Is this what you call home?

For my parents, the question doesnt recede. They just roll up their sleeves and re-create the home they left behind, and, unlike me, they seem to know exactly what that requires. By the time I am in high school, they and their Calcutta friends bring over their most vital piece of home: Ma Durga, the mother goddess herself, who arrives at Los Angeles International Airport, all ten arms intact. Made of plaster of paris on the edge of Calcuttas most storied red-light district, Durga is stashed away in a friends garage in another Southern California suburb, only to be brought out every fall and worshipped with ululations and prayers. A friend of my parents, a Brahmin by blood right, performs the service. Baba prepares the offering: an enormous vat of slow-cooked, chili-bathed mutton.

Next page