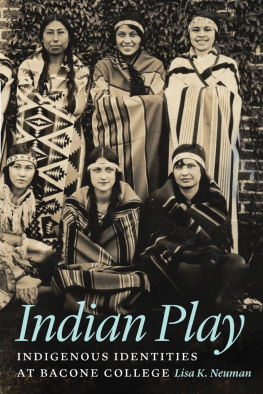

Lisa K. Neuman - Indian Play

Here you can read online Lisa K. Neuman - Indian Play full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: University of Nebraska Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Indian Play

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Nebraska Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Indian Play: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Indian Play" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Indian Play — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Indian Play" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

2013 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Portions of the introduction, chapter 7, and the conclusion originally appeared as Indian Play: Students, Wordplay, and Ideologies of Indianness at a School for Native Americans, American Indian Quarterly 32, no. 2 (2008): 178203. 2008 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska and used by permission of the University of Nebraska Press.

Portions of chapters 1, 2, 3, and 4 originally appeared as Selling Indian Education: Fundraising and American Indian Identities at Bacone College, American Indian Culture and Research Journal 31, no. 4 (2007): 5178. 2007 by the Regents of the University of California, and used by permission of the American Indian Studies Center, UCLA .

Portions of chapters 5 and 6 originally appeared as Painting Culture: Art and Ethnography at a School for Native Americans, Ethnology 45, no. 3 (2006): 17392. 2006 by the University of Pittsburgh.

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Neuman, Lisa Kay, 1968

Indian play: indigenous identities at Bacone College / Lisa K. Neuman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8032-4099-5 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Bacone CollegeHistory. 2. Indians of North AmericaEducation (Higher)Oklahoma. 3. Indians of North AmericaOklahomaEthnic identity. 4. Education, HigherOklahomaPhilosophy. 5. Indian philosophyOklahoma. I. Title.

E 97.6. B 3 N 48 2013

378.0089709766dc23 2013020384

Set in Lyon by Laura Wellington.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Dedicated to All Baconians ,

Past, Present, and Future

Illustrations

MAPS

2. Bacone campus, 1941

FIGURES

Preface

I engaged a variety of research techniques during my fieldwork in Oklahoma, which was conducted from January 1994 until December 1995. I personally interviewed forty-six former Baconians (most of them alumni). I also used telephone interviews and a written questionnaire to reach a larger number of alumni living out of state. In all, more than one hundred former Baconians participated in this project. While personal interviews provided strong data on feelings, identities, and the meanings of specific events, questionnaire responses tended to provide data on students motivations for attending Bacone, their favorite courses and teachers, and extracurricular activities in which they participated. Moreover, two years of participant observation while living in eastern Oklahoma and attending reunions and alumni events revealed the things that alumni and former teachers found to be most important about Bacone, and I discovered the enduring bonds that had formed among many former Baconians. Through time spent traveling around the state of Oklahoma, sometimes staying as the guest of Bacone alumni, I was able to get a glimpse of their interactions within their own families and tribal communities and also observe their families impressions of Bacone.

I conducted primary archival research at Bacone College in Muskogee, Oklahoma; at the Philbrook Museum of Art and the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma; at the American Baptist Historical Society at the Samuel Colgate Historical Library in Rochester, New York; and at the American Baptist Historical Society Archives Center at the American Baptist Mission Center in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania (materials from the last two sites are now located at the American Baptist Historical Society in Atlanta). This work gave me crucial access to official reports and correspondence, providing insight into the values, goals, and actions of Bacones administrators, local museum directors, and American Baptist leaders things former students could not have been expected to know in any depth. In terms of the amount and variety of historical material available, I was lucky: there were plenty of newspaper accounts, letters, yearbooks, photographs, and reports that I could consult. Many of these were located in boxes and folders in a locked room in the basement of the Bacone College Library, referred to as the Indian room. The materials from the Indian room are now located in the American Indian Research Library at Bacone College in Muskogee, Oklahoma. Most important among these sources was the Bacone Indian , a biweekly student newspaper that began publication in 1928. The Bacone Indian showcased a large number of articles written by students, and the paper was a primary site where students articulated their ideas about what it meant to be Indian at school. The Bacone Indian was almost entirely student-run, and its content was largely student-produced, making it strikingly different from newspapers at some other Indian schools during this time where school administrators censored student writings. Documents like the Bacone Indian helped to confirm the details of specific dates, places, and events far removed from the memories of alumni. Taken together, these various research strategies afforded me a much broader picture of life at Bacone than any single research method alone could have provided.

While I was interviewing them in the mid-1990s, Bacone alumni did clearly manifest some of the processes of cultural creativity that they had demonstrated while students. Indeed, I sensed that for some alumni, participating in my project was a way of emphasizing and rearticulating their present-day identities; and, from a methodological perspective, the meanings of students past experiences were often made clearer to me in the context of the present-day uses of identity that I often observed. Alumni often chose to emphasize fundamental connections between their present-day and past identities and experiences. For example, when some non-Native alumni playfully stated that they were not Indians but really Sycamores (the term used at Bacone for white students), or that they were members of the Sycamore Tribe, they were not simply emphasizing their present-day identities as whites. Instead, they were actually demonstrating for me exactly how, at Bacone, they and other students had negotiated the relationship between whiteness and Indianness by using forms of creative wordplay.

While in the field, I was frequently reminded of the often difficult and complex relationship between anthropologists and Native Americans, whose cultures have often formed the basis for ethnographic research but who have often been treated as objects of study rather than partners in scholarship. For example, when I arrived for one interview with a Choctaw alumnus, he smiled and quickly pulled out a small 35-millimeter camera and snapped a picture of me. There, he said, now I will remember what you looked like! A few weeks later, a Creek alumna I was interviewing remarked, You are very interesting to observe, did you know that? These pointed remarks were intentional reminders to me that our relationships would not be the traditional one between anthropologist and informants. These two Baconians were astutely turning the tables on traditional power relationships that have often characterized anthropological field experiences with indigenous communities and that too often show up in anthropological writings.

If Baconians sometimes used biting humor to subvert the traditional roles of anthropological researcher and informant, they also could be very serious and direct about the negative reputations of anthropologists and the past mistakes they had sometimes made in working with Indian communities. For example, one alumnus I got to know over the course of my fieldwork continually reminded me that his Kiowa grandparents had been robbed of many important possessions, spiritual objects, and artistic works by earlier anthropologists who had taken these objects and put them in a museum in Washington DC (likely the Smithsonian). Other alumni hoped that I could help them recover items that had been taken to local museums. In one case, I was asked to retrieve a photocopy of a diary that was kept in a display case at Ataloa Lodge Museum and that had once belonged to a Cherokee mans grandfather. With the help of the museum director (then Bacone alumnus Tom McKinney), I was able to return a photocopy of the grandfathers diary to his grandson.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Indian Play»

Look at similar books to Indian Play. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Indian Play and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.