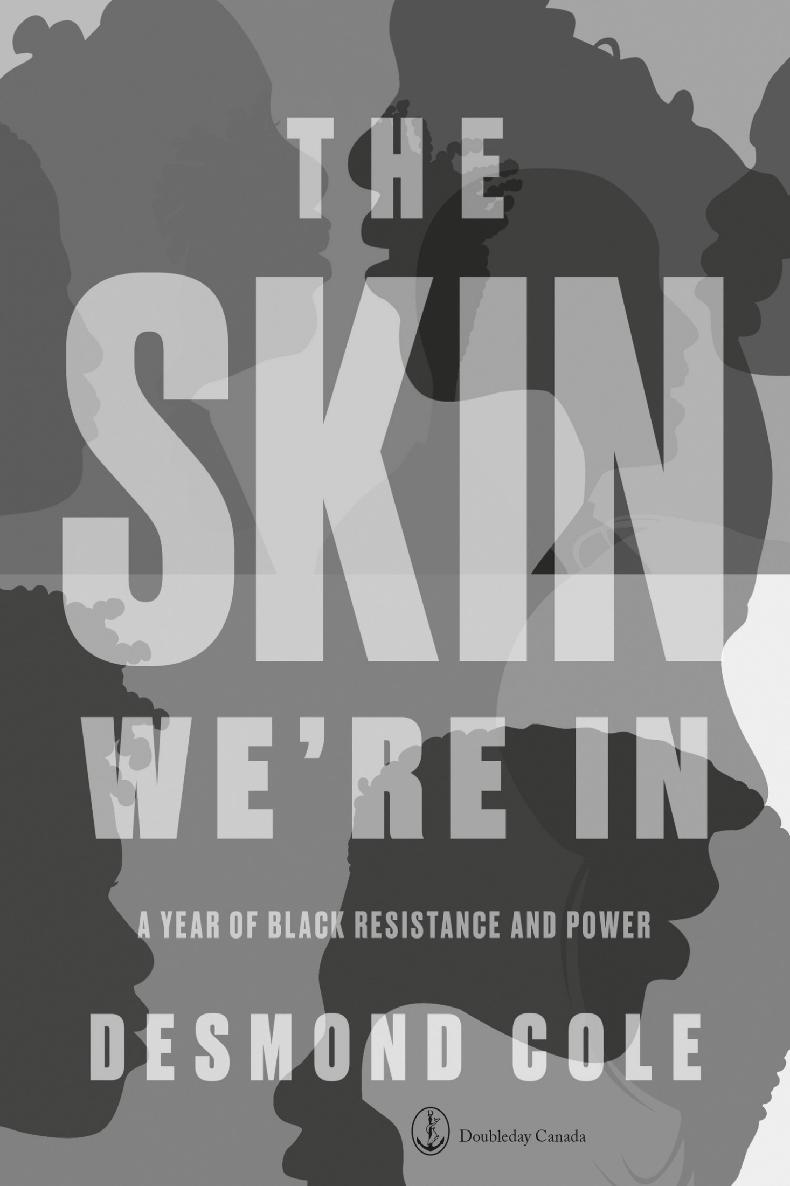

Copyright 2020 Desmond Cole

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisheror in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

Doubleday Canada and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Limited.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: The skin were in / Desmond Cole.

Other titles: Skin we are in

Names: Cole, Desmond, 1982- author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190050993 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190051124 | ISBN 9780385686341 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780385686358 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: CanadaRace relations. | LCSH: Discrimination in law enforcementCanada. | LCSH: Discrimination in criminal justice administrationCanada. | LCSH: Police misconductCanada. | LCSH: Police brutalityCanada. | LCSH: Race discriminationCanada. | LCSH: MinoritiesCrimes againstCanada. | LCSH: Police-community relationsCanada. | CSH: Black CanadiansSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC FC106.B6 C65 2020 | DDC 305.896/071dc23

Book design: Terri Nimmo

Cover and title page images: smartboy10 / Getty Images

Interior image ( ): Uranranebi Agbeyegbe

Published in Canada by Doubleday Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

v5.4

a

For Adora

contents

negro frolicks

(january)

I remember wanting to escape the year 2016 like a kid in a haunted house, dashing from whatever real or imagined demon was chasing me. Running into empty space, terrified to look backthat was 2016. I imagine some Canadians remember it as the year a lot of beloved American artists and cultural figures diedPrince, Muhammad Ali, Carrie Fisher, Gene Wilder, Malik Phife Dawg Tayloror the year that disgraceful celebrity was elected president of the United States. Were usually better at American culture and history than our own.

I marked the year 2016 through setbacks and losses closer to home. I mourned the deaths of Black people, many of whom I had never met or previously heard of, and more often I witnessed the ever-present impediments to Black life: policing, public education, prisons, the apprehension of our children, the discrimination against our parents at work, the disrespect of our elders on public transit.

I kept track of the violence done to Black people in my city, Toronto, and my country, Canada, as if it was being done to me, because it was, because it is, because thats what Black people are facing in Canada and around the world, and Id never been more aware of it.

In 2016 I documented Black Lives MatterTorontos Tent City demonstration, a sixteen-day protest in front of Toronto Police headquarters during an unseasonably cold spring. The demonstrators were responding to a series of public injustices against local Black people, especially the decision not to criminally charge Andrew Doyle, a Toronto police officer who shot and killed a Black man named Andrew Loku in 2015.

At the time of the protest Doyle had not yet been publicly identified as the killer, despite months of campaigning by Black people. I hadnt seen this kind of demonstration of Black resistance in my adult life. I felt so connected to it that I not only reported from Tent City as a journalist, but I slept in it, helped clean it, kept watch over it at night. The demonstrators who maintained the camp day and night had opened a critical space for us to speak, to connect, to grieve, to hold each other.

During my reporting I met a recently arrived Black Tanzanian teenager named Michelle Erin Hopkins, who had been living in and helping to maintain the camp for a week. The police had attacked, beaten, and gassed protesters during their first full day of peaceful demonstration, and I was surprised that after so little time in Canada, this fifteen-year-old was so committed to engaging in such dangerous resistance of anti-Black racism.

You cant ask people who have been oppressed their whole livesto forget that and to ignore the fact that it might be happening again, Hopkins told me. The truth she spoke is a Black birthright, an inherited knowledge we need in order to survive no matter where we find ourselves in the world.

People who refuse to acknowledge the fact that Canada has its race problems compare us a lot to America, Hopkins went on. They say, Canadas not like America. Why are you bringing American problems into Canada? Why are you crossing borders? But thats the thingBlack lives have no borders. We exist everywhere regardless of the fact they may not want us to.

The year was full of painful reminders that Black people are not wanted in Canada, that this is a land stolen from Indigenous peoples and ultimately colonizedjust like my parents native land of Sierra Leoneby white British settlers.

I danced away the final hour of 2016 in my own apartment with a couple of close friendswe drank champagne and sang and lit dollar-store sparklers. I needed the celebration. I grew up in Oshawa, a city about half an hours drive east of Toronto. I can remember a New Years party my parents hosted in the partly finished basement of our suburban home. I remember my relatives singing after the stroke of midnight. We didnt sing Auld Lang Syne, the New Years song that no one here seems to know the words to. My relatives sang in Krio, our native language, Happy new year, me no die oh! Tell God tenkithank youfor long life!

In my head I sing that song every New Years. I think about my relatives teaching me, in direct and subtle ways, that although Black people deserve far more than survival, survival alone is worth celebrating.

I woke up on the first morning of 2017 and made my friends pancakes with fruit and maple syrup. After they left I stared out my window, enjoying the tranquility of New Years Day, the feeling that for at least a few hours nothing was going to happen. But the years first local, well-publicized crisis of Black existence had already happened. As I sat on my couch scanning my Twitter feed, I saw posts about a young Black artist named John Samuels who had been attacked by the police in his art gallery on New Years Eve. According to John, police had disrupted the gathering he was hosting, then repeatedly jolted him with a taser while his stunned guests admonished the police and filmed the attack on their cellphones.

My stomach somersaulted in my belly. In these moments of shock I sometimes ask Why? but its more of a lament than a question. I already know why police choose, over and over and over again, to intimidate and attack and harm and kill Black people in my city, in Canada. It has nothing to do with any single incident, any presumed provocation or threat or misunderstanding. The police are just doing their job: a central responsibility of policing has always been to discipline Black people on behalf of the ruling class.

Johns art gallery was within walking distance of my apartment. I wanted to jog over right away until I remembered it was a holiday and that John had just spent his New Years Eve in jail and likely wouldnt be there. The recognition of what Id just read came in waves. I started to plan, to anticipate what John and his friends might need and how I might be able to help. This is how 2017 beganmeet the new year, same as the old year.

Next page